Alabama, 1933. A caravan of black limousines carries gangsters from a gold mining town in Colorado to a rural Alabama area where slavery still survives as an institution. Alabama looks uncannily like Colorado, as it must: The story that began in Lars Von Trier’s “Dogville” (2003) continues here, with the same visual strategy of placing all the action on a sound stage, with chalk lines indicating the outlines of locations. A few rudimentary props flesh out the action, including doors, windows, and machineguns.

The movie is the second in a trilogy by Von Trier, who has never visited the United States but has set several movies here, all of them generated by his ideas about American greed, racism and the misuse of power. To say his America is not recognizable to any American is beside the point; neither is the America in most Hollywood entertainments. Presenting imaginary worlds as if they were real is how movies work.

Von Trier’s purpose is fiercely polemical. The Danish iconoclast holds strong ideas about our society, and expresses them in satiric allegories of such audacity that we cast loose from realism and simply float with his conceits. The crucial difference between “Manderlay” and the almost unbearable “Dogville” is not that his politics have changed, but that his sense of mercy for the audience has been awakened. The movie is 38 minutes shorter than “Dogville” (although none too fleeting at 139 minutes), and the story is more clearly and strongly told.

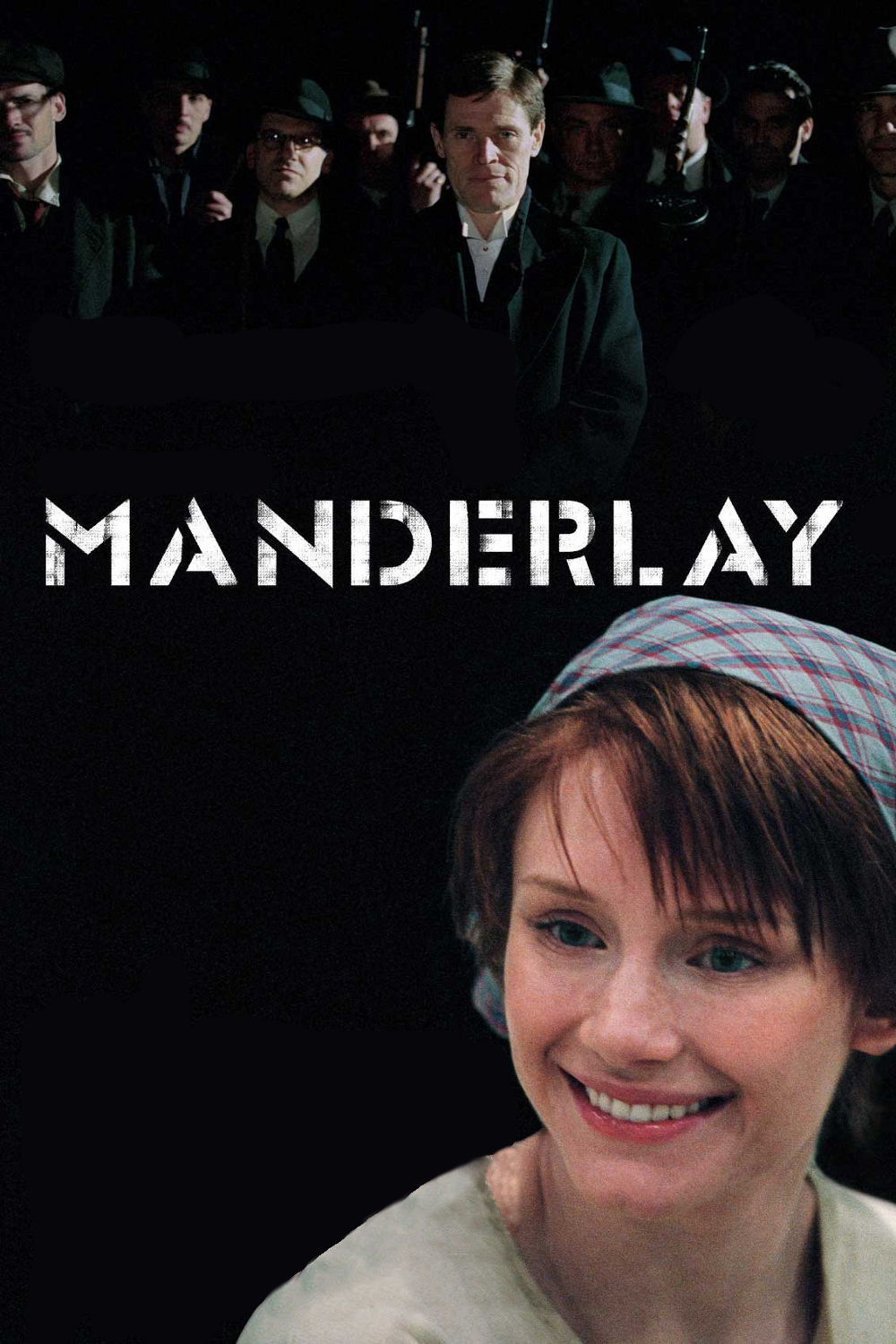

He begins with a plantation in Alabama where slavery has never been abolished: Mam (Lauren Bacall) rules with a iron hand, assisted by her foreman Wilhelm (Danny Glover), a slave who believes his people are not ready for the responsibilities of freedom. Driving up to the gates of the imaginary plantation, Grace (Bryce Dallas Howard) and her gangster father (Willem Dafoe) are surprised to find slavery still flourishing. Grace declares this cannot be, that the plantation must be informed of such historical events as the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation.

Grace’s father has crimes to commit, and wants to keep moving: “This is a local matter,” he tells his daughter, echoing the argument used for generations. She thinks not, and persuades him to leave behind a lawyer and four thugs with machineguns. Using brute force if necessary, she will impose democracy on this backwater. Von Trier’s parallels with Iraq are not impossible to find; this Alabama is no more fictional than the pre-war Iraq depicted by the neocon advocates of war.

Mam dies soon after Grace frees the slaves, and Grace herself steps into the power vacuum, establishing a benevolent transitional authority. She will teach the slaves to vote, and then hold elections. Soon, but not yet, they will govern themselves. Doubts are expressed by the slave Wilhelm, who cites the insights in a book hidden under Mam’s mattress — a volume categorizing the various kinds of slaves and their abilities. The slaves, he says, have grown accustomed to the plantation routine; dinner under Mam was always at 7 but what time will it be if the matter is open for discussion? And who will plant the crops and plan the harvest? Jobs don’t get done by themselves.

Grace has her gangsters wear blackface and serve dinner to the slaves, who find the exercise offensive. She orders crops planted, and rejoices at the harvest, although gamblers arrive to cheat the slaves, and company stores recycle the wages right back into the pockets of those who pay them. Again, there are contemporary parallels: One of the purposes of every colonial exercise is to open up markets for the occupying power.

I wouldn’t go so far as to claim “Manderlay” is fun to watch. Von Trier, who can made compulsively watchable films (“Breaking the Waves“), has found a style that will alienate most audiences. Maybe it’s necessary. On his bargain budgets, he certainly couldn’t afford to shoot on a real plantation, with period detail. His actors work for peanuts (and even so, Nicole Kidman and James Caan bailed out after “Dogville”). The stark artificiality of his sets makes it clear he’s dealing with parable, and excuses his story from any requirement of reality. The real action generated by his story begins after the film ends. If audiences still exist for movies like this and debate them afterward — if, that is, not every single moviegoer in America is lost to mindless narcissistic self-indulgence — the arguments afterward will be the real show. Many moviegoers are likely to like the film less than the discussions it drags them into.

The film has a closing montage of photographs showing the history of African-Americans in America, from slavery through decades of poverty and discrimination to the civil rights movement, both its victories and defeats. Von Trier no doubt intends this montage to be an indictment of America, but I view it more positively: From a legacy of evil, our democracy has stumbled uncertainly in a moral direction and within our lifetimes has significantly reduced racism. No doubt if everyone in America had always been Danish, we could have avoided some of our sins, but there you have it.

Footnote: Just in time to be tacked onto the end of this review, Von Trier has issued a “statement of revitality” to Variety. Ray Pride of Movie City News quotes him in part: “…I intend to reschedule my professional activities in order to rediscover my original enthusiasm for film. Over the last few years I have felt increasingly burdened by barren habits and expectations (my own and other people’s) and I feel the urge to tidy up. In regards to product development this will mean more time on freer terms; i.e. projects will be allowed to undergo true development and not merely be required to meet preconceived demands. This is partly to liberate me from routine, and in particular from scriptural structures inherited from film to film …”

The most delightful element of this statement is his assumption that his films are “required to meet preconceived demands.”