I’ve been thinking about Whoopi Goldberg’s appeal, which is real but elusive, I think it has something to do with a directness of style. There are no false highs and lows in her performances, no flourishes for effect. She seems to respond directly to the situation at hand. This quality provides a leveling effect for “Made in America,” a movie that could have been all over the map emotionally, but turns out to be surprisingly effective.

In the movie, Goldberg plays Sarah Mathews, who runs an African-American bookstore in Oakland, and is raising Zora, a daughter of college age (Nia Long). Goldberg’s husband died many years ago, and Zora has always assumed he was her father. Then she discovers by accident that she was the product of artificial insemination. And in a raid on a sperm bank computer, she discovers that her biological father is a white man. And, to her horror, he’s one of the biggest jerks in town, Hal Jackson, the cornpone car dealer who makes a fool of himself in his TV ads.

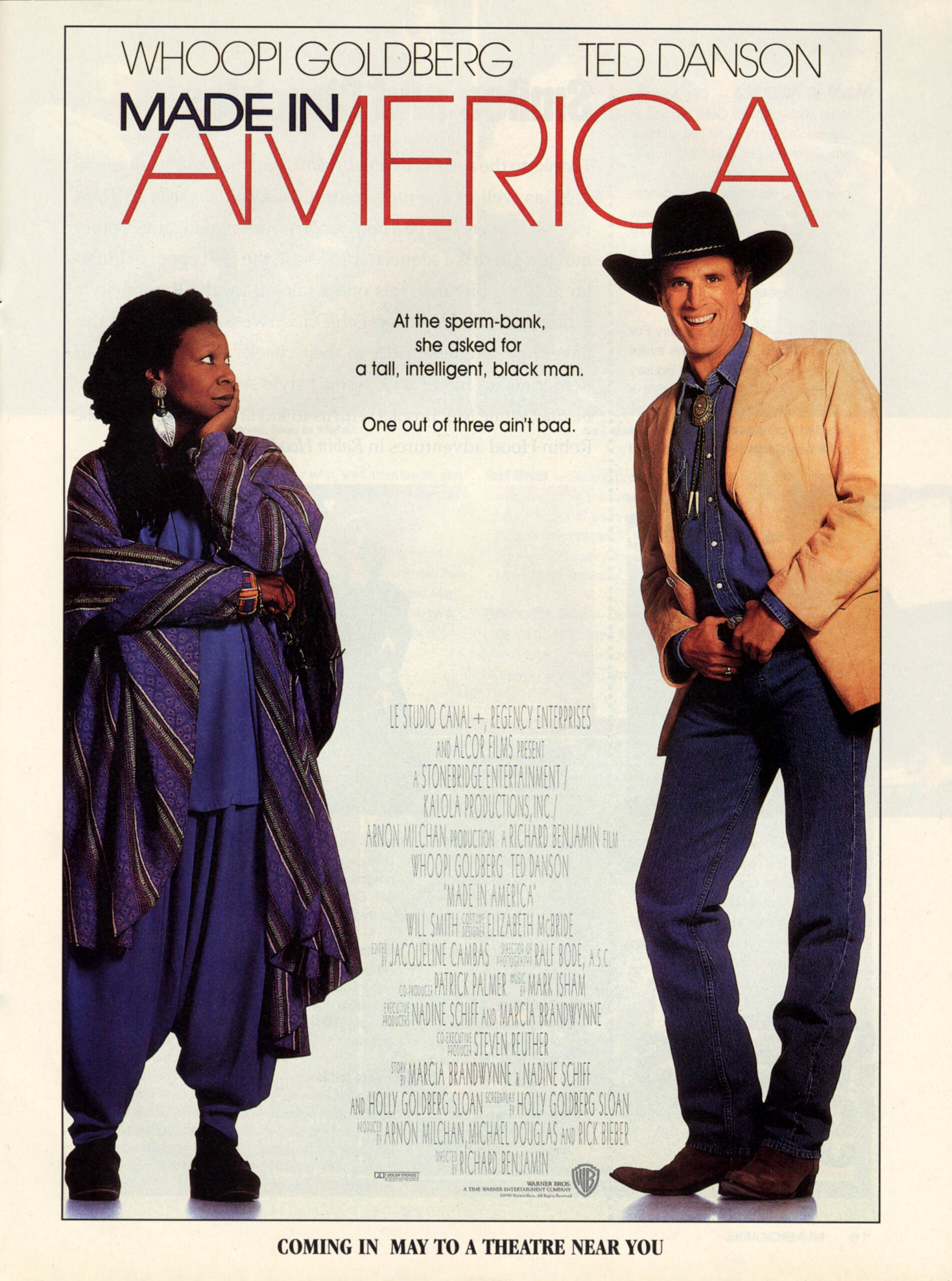

Zora is devastated. So is Sarah, who specified to the sperm bank that the father be black. So, when he finds out, is Hal Jackson (Ted Danson), a committed bachelor with no in terest in planning, starting, or retrospectively discovering a family.

The movie’s setup is not subtle. Character touches are added with a trowel. What purpose is served, for example, by showing that the Goldberg character rides her bicycle through traffic without the slightest caution, cutting in front of cars and trucks as if they were not there? Of course that sets up her accident, which sends her to the hospital and leads to further important plot developments, but it’s so goofy – such an obviously phony gimmick – that the writers should have found another way to get her to the hospital.

The strange thing is, after a while it doesn’t matter. The ham-handed first 45 minutes of the movie set up a situation which the rest of the film handles with increasing effectiveness. The Danson character, a grotesque caricature when we first see him, calms down into a nice guy with a heart. And once the dust has settled from all the busyness of the setup, “Made in America” becomes actually heartwarming.

A lot of that is because of Goldberg. As the plot swoops and turns, as melodramatic revelations are followed by manufactured brushes with death, she forges steadily onward, her eye on the main line of the screenplay, which has to do with what it means to be a parent, or a child. Her daughter’s self-image is seriously affected by the discovery of a white father, just as Danson finds it astonishing to possess any child at all. Since we can more or less guess where the plot is heading (there is a surprise, but the main lines are clear), the movie stands or falls on how much emotional honesty and human comedy it can find between the lines.

It finds a lot. Once the Danson character has toned down his original excesses, once the daughter has discovered that nature can be colorblind, once the mother has drawn everyone together with her sanity, the movie proceeds to its conclusion with warmth and conviction. This isn’t a great movie, but it sure is a nice one.