At a midpoint in Martin Scorsese’s “Kundun,” the 14th Dalai Lama reads a letter from the 13th, prophesying that religion in Tibet will be destroyed by China–that he and his followers may have to wander helplessly like beggars. He says, “What can I do? I’m only a boy.” His advisers say, “You are the man who wrote this letter. You must know what to do.” This literal faith in reincarnation, in the belief that the child at the beginning of “Kundun” is the same man who died four years before the child was born, sets the film’s underlying tone. “Kundun” is structured as the life of the 14th Dalai Lama, but he is simply a vessel for a larger life or spirit, continuing through centuries. That is the film’s strength, and its curse. It provides a deep spirituality, but denies the Dalai Lama humanity; he is permitted certain little human touches, but is essentially an icon, not a man.

“Kundun” is like one of the popularized lives of the saints that Scorsese must have studied as a boy in Catholic grade school. I studied the same lives, which reduced the saints to a series of anecdotes. At the end of a typical episode, the saint says something wise, pointing out the lesson, and his listeners fall back in amazement and gratitude. The saint seems to stand above time, already knowing the answers and the outcome, consciously shaping his life as a series of parables.

In “Kundun,” there is rarely the sense that a living, breathing and (dare I say?) fallible human inhabits the body of the Dalai Lama. Unlike Scorsese’s portrait of Jesus in “The Last Temptation of Christ,”this is not a man striving for perfection, but perfection in the shape of a man. Although the film is wiser and more beautiful than Jean-Jacques Annaud’s recent “Seven Years in Tibet,” it lacks that film’s more practical grounding; Scorsese and his writer, Melissa Mathison, are bedazzled by the Dalai Lama.

Once we understand that “Kundun” will not be a drama involving a plausible human character, we are freed to see the film as it is: an act of devotion, an act even of spiritual desperation, flung into the eyes of 20th century materialism. The film’s visuals and music are rich and inspiring, and like a mass by Bach or a Renaissance church painting, it exists as an aid to worship: It wants to enhance, not question.

That this film should come from Scorsese, master of the mean streets, chronicler of wiseguys and lowlifes, is not really surprising, since so many of his films have a spiritual component, and so many of his characters know they live in sin and feel guilty about it. There is a strong impulse toward the spiritual in Scorsese, who once studied to be a priest, and “Kundun” is his bid to be born again.

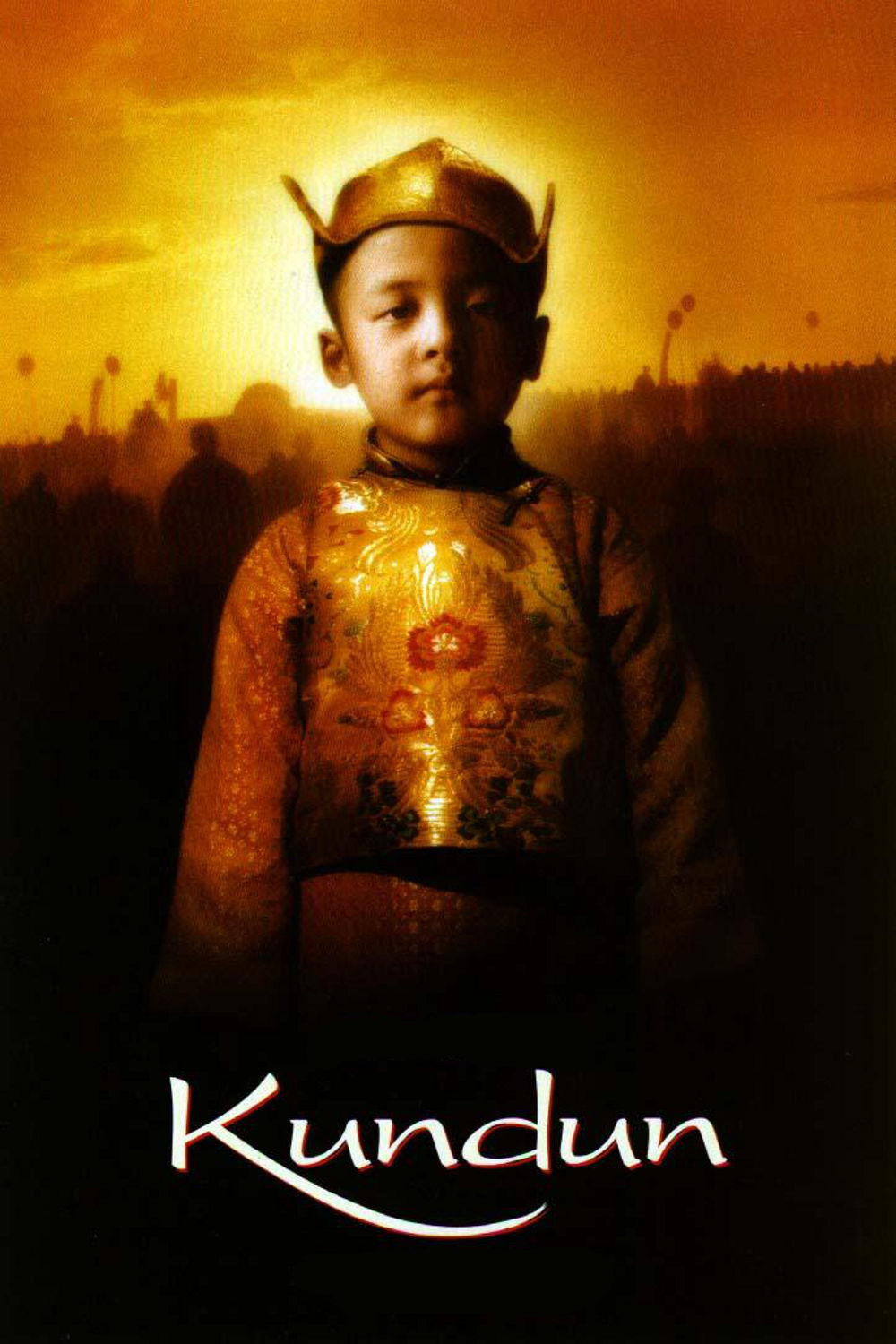

The film opens in Tibet in 1937, four years after the death of the 13th Dalai Lama, as monks find a young boy whom they sense may be their reincarnated leader. In one of the film’s most charming scenes, they place the child in front of an array of objects, some belonging to the 13th, some not, and he picks out the right ones, childishly saying, “Mine! Mine! Mine!” Two years later, the monks come to take the child to live with them and take his place in history. Roger Deakins’ photography sees this scene and others with the voluptuous colors of a religious painting; the child peers out at his visitors through the loose weave of a scarf and sits under a monk’s red cloak as the man tells him, “You have chosen to be born again.” At his summer palace, he sees dogs, peacocks, deer and fish. He is given a movie projector, on which a few years later he sees the awful vision of Hiroshima. Soon the Chinese are invading Tibet, and he is faced with the challenge of defending his homeland while practicing the tenets of nonviolence. There is a meeting with Chairman Mao, at which the Dalai Lama hears that religion is dead. The Dalai Lama can no longer look in the eyes of a man who says such a thing, focusing instead on Mao’s polished Western shoes, which seem to symbolize the loss of older ways and values.

The film is made of episodes, not a plot. It is like illustrations bound into the book of a life. Most of the actors, I understand, are real Tibetan Buddhists, and their serenity in many scenes casts a spell. The sets, the fabrics and floor and wall coverings, the richness of metals and colors, all place them within a tabernacle of their faith. But at the end I felt curiously unfulfilled; the thing about a faith built on reincarnation is that we are always looking only at a tiny part of it, and the destiny of an individual is froth on the wave of history. Those values are better for religion than for cinema, which hungers for story and character.

I admire “Kundun” for being so unreservedly committed to its vision, for being willing to cut loose from audience expectations and follow its heart. I admire it for its visual elegance. And yet this is the first Scorsese film that, to be honest, I would not want to see again and again. Scorsese seems to be searching here for something that is not in his nature and never will be. During “The Last Temptation of Christ,” I believe Scorsese knew exactly how his character felt at all moments. During “Kundun,” I sense him asking himself, “Who is this man?”