Food documentaries seem to be almost as plentiful nowadays as new restaurant openings. For all the grousing we U.S. citizens do about jobs and the economy, almost every major urban area in the country seems to have a thriving, and in some cases, obnoxious, gourmand or “foodie” culture, and that culture’s always, um, hungry for the next startling taste.

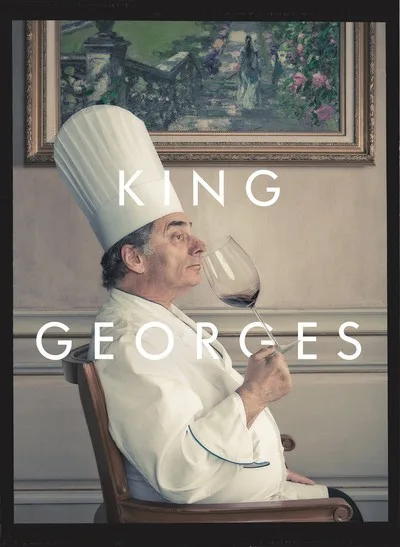

“King Georges,” the directorial debut of longtime documentary producer Erika Frankel, will prove a frustrating experience for a good number of its viewers, I reckon, because it’s about a restaurant they’ll never be able to go to as opposed to a restaurant they’re very unlikely to ever get into although they’d be welcome to try. Its subject is the chef Georges Perrier and his restaurant was Le Bec-Fin (approximately: “The Sharp Beak,” as the master explains), and it was not just the premiere French restaurant in Philadelphia (not really a huge distinction in and of itself in the ‘70s, when the city’s most notable culinary draws were cheesesteaks) but possibly in all the United States. Perrier, a man of no small consideration of his own work ethic, skills, and achievement, calls it the “only” French restaurant in the United States.

Frankel’s movie is a brisk (less than an hour and fifteen minutes), fat-free portrait of a culinary artist in changing times. It begins with Perrier visiting a food warehouse ridiculously early in the morning, chatting amiably with vendors about being part of a dying breed. The voluble Perrier speaks in a heavy enough accent that Frankel uses subtitles throughout, and his English still has vestigial idiosyncrasies: a longtime fan of the Philadelphia Eagles, he’s seen at times in the restaurant’s downstairs bar watching a football game, and he observes to a colleague that his team scored a touchdown in “the second inning.” But when the going gets tough, Perrier can curse like a Brooklyn born-and-bred longshoreman of the old and scary school. When the restaurant was in its early days and patrons could hear Perrier lose his temper in the kitchen, a maître d’ observes, the general reaction was “oh how cute, a real French chef.” Gordon Ramsay’s stardom notwithstanding, kitchen tantrums are no longer considered adorable, and when Perrier’s arrives, about 20 minutes in, it’s a doozy. Someone has overcooked the galettes, and boom, to the floor they go, and Perrier huffs and puffs and swears and uses what they now refer to as “ableist” language, using an epithet that once got Britney Spears (of all people) into hot water. It’s not pretty, but it’s different from a Ramsay explosion; it doesn’t have quite the same theatricality. It’s forgivable in a sense because it’s entirely sincere. “If I’m hard on other, I’m just as hard on myself,” Perrier says in the film. From most people that’s a weak and cowardly excuse, but Frankel makes it a credible one. The movie also show’s Perrier’s humor, and his talents as a mentor. His relationship with future “Top Chef” winner Nicholas Elmi is depicted as both trying and affectionate. Elmi is interested in keeping up with the times, and trends. “If we’re not gonna put cream in the sauce … ” he beings one sentence. Quelle horreur!

The movie chronicles both the end of an era and the passing of a torch. The account of Perrier’s apprenticeship in Lyon, in the days before (as he puts it) being a chef was “a gentleman’s profession” is brief but eye-opening. And the depiction of an evening’s preparation at Le Bec-Fin is equally revealing, showing that perhaps every great mean is the result of squelching dozens of potential disasters along the way to the plating. The score, a kind of casual-lite extrapolation of Erik Satie sounds by Michael Montes, is as elegant as the food depicted. Like the 2011 film “Jiro Dreams Of Sushi,” “King Georges” reminds us that a singular dining experience can often be the expression of a very singular personality, singular temperament, singular discipline. Beyond all that, I am rather mournful that I’ll never get to taste Georges Perrier’s crab cakes with mustard sauce.