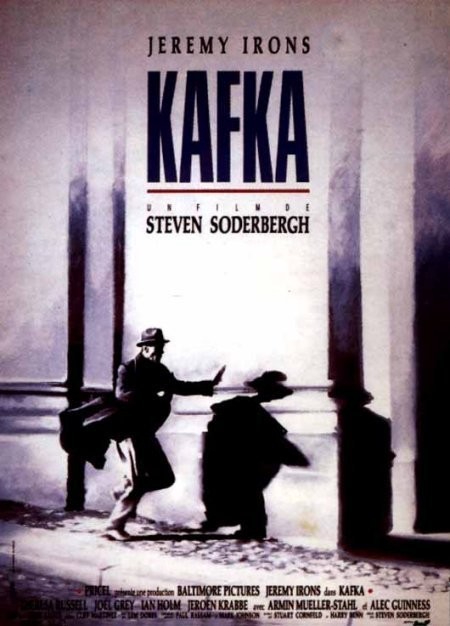

The story of Steven Soderbergh’s first film, “sex, lies, and videotape,” is by now well-rehearsed: how he wrote the screenplay on legal pads during an eight-day drive to Hollywood, how he found independent financing and persuaded his actors to work on spec, how the film conquered the Cannes Film Festival and went on to be a surprise hit. What we now discover with “Kafka,” Soderbergh’s second film, is that there was a gothic stylist lurking inside the man who made such a spare and stark debut.

If “sex, lies, and videotape” took place in a world of neatly furnished apartments and unremarkable cityscapes, “Kafka” seems located within a set designer’s nightmare. The movie takes place in a Prague more or less like the imaginary cities of Franz Kafka’s fiction, and then it moves to an interior set that seems inspired by “Bride of Frankenstein,” crossed with “Re-Animator.” The movie commences in black and white, but switches to color for the sci-fi climax, in which cross-sections of the human brain are projected on huge, pulsating screens, reminding me of nothing so much as the psyche of J. Alfred Prufrock, pinned wriggling to a wall.

The movie stars Jeremy Irons, looking cadaverous and wan, as a fictionalized version of the great Czech writer. He inhabits a world that owes something to Kafka’s fiction and a great deal to other movies. The vast insurance office he works in, for example, reminds us of a similar set in Orson Welles’ version of kafka’s “The Trial” (not to mention Jack Lemmon’s office in Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment”). At home, he writes short stories, including one about a man’s transformation into a cockroach, and grows concerned about the disappearance of an acquaintance, Eduard.

It is hard to say what Eduard meant to him, but when he meets Eduard’s lover, Gabriela (Theresa Russell), there is an opportunity for a retread of “The Third Man” if only he will develop a great passion for her. Passion is, of course, an unknown language for Kafka, and so the search for Eduard procedes less like a quest than like a research project.

Of all the great writers, Kafka may be the hardest to film, since his stories have their centers in the minds of reclusive, self-despising men who think mostly about themselves; Welles’ “The Trial,” brilliant though it was, did not solve this problem – because it took what was really the hero’s internal feelings of persecution and made them real, and external to him.

“Kafka” tries to avoid this problem by being about the author rather than his characters, but as written by Lem Dobbs and played by Irons, Kafka is a fish out of water. He belongs lost in his existential reveries, and it is more than a little bizarre to see him transported into the Mad Scientist genre, climbing ladders over domes upon which are projected the interiors of brains.

Why did Soderbergh make this movie? Probably because he admires the work of Kafka, and possibly because inside every filmmaker there throbs the desire to make a gothic black-and-white melodrama set in a mysterious and beautiful city. These are legitimate feelings, but should not have been brought to the same project. Kafka, as subject or character, simply doesn’t fit into the world of this film. Soderbergh does demonstrate again here that he’s a gifted director, however unwise in his choice of project. Maybe he should take another eight-day drive with a legal pad.