Just when John Wick thought he was out, they pull him back in.

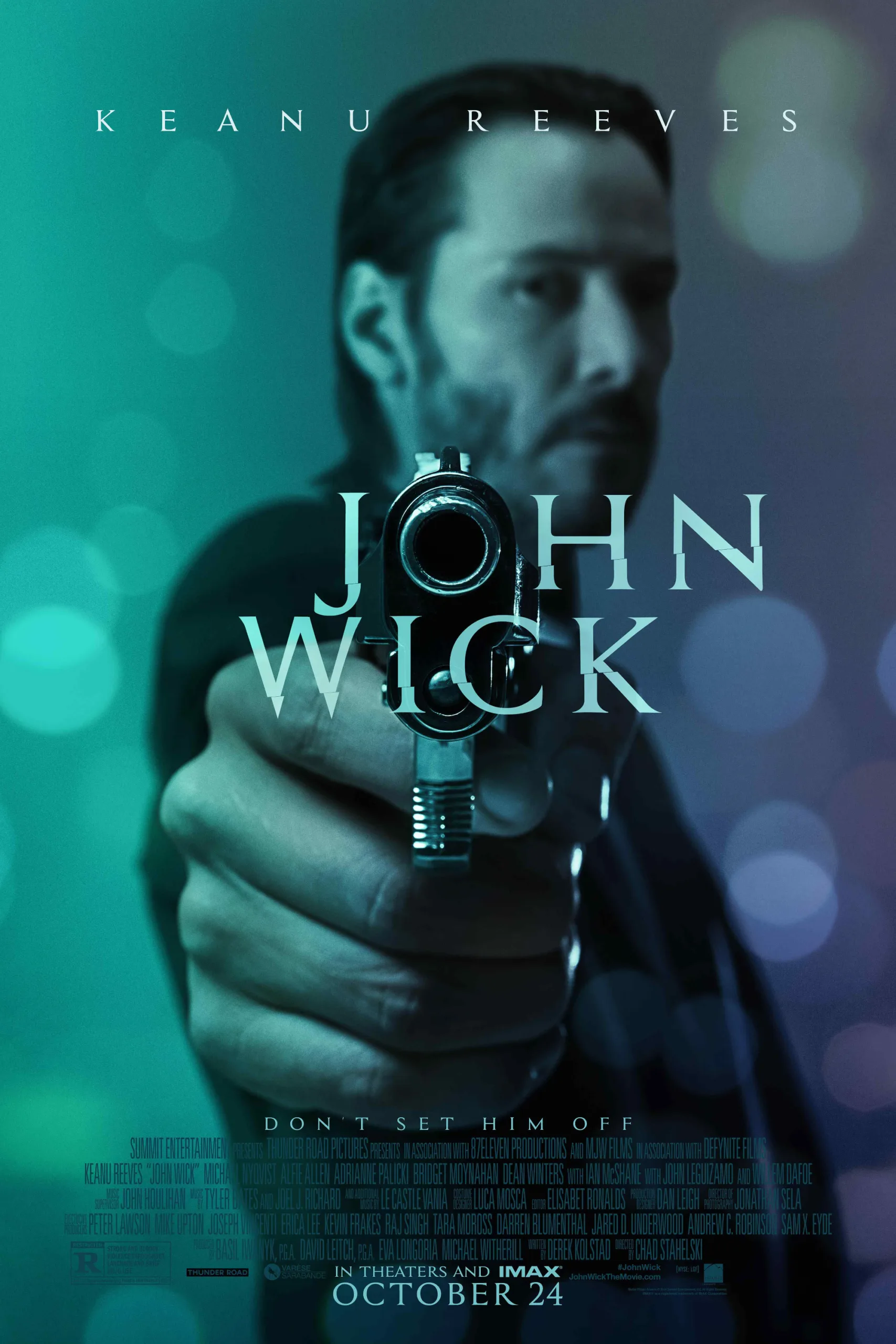

It’s the tried-and-true formula of one last job/heist/assignment. A longtime bad guy leaves the life of crime in pursuit of peace and quiet, but naturally gets dragged back to his old haunts and habits to settle a final score. But “John Wick” breathes exhilarating life into this tired premise, thanks to some dazzling action choreography, stylish visuals and–most importantly–a vintage anti-hero performance from Keanu Reeves.

Toward the end of the film, a menacing Russian mobster remarks that the veteran hit man John Wick looks very much like the John Wick of old. Keanu Reeves looks very much like the Keanu Reeves of old, as well. Elegantly handsome and athletically lean, he looks fantastic at 50 and is comfortably, securely back in action-star mode. Not that he’s been gone that long–or deviated that much from his persona–but this later-stage butt-kicking does call to mind Liam Neeson’s recent resurgence in movies like “Taken,” “The Grey” and “Non-Stop.”

After all these years, though, he’s still quintessentially Keanu. He radiates a Zen-like calm which makes him simultaneously elusive and irresistible, especially in the face of great mayhem. There’s still a boyish quality to his face but it belies the wisdom of his years. He’s smarter than he looks but he’s in no great hurry to go out of his way to prove it to you–at least, not on screen. He just … is.

A character like John Wick is right in Reeves’ wheelhouse because it allows him to be coolly, almost mythically confident, yet deliver an amusing, deadpan one-liner with detached precision. (This is when traces of the playful characters of his youth–Ted “Theodore” Logan and Johnny Utah–take a moment to surface.) But when the time comes–and it comes often in “John Wick”–he can deliver with a graceful yet powerful physicality.

Soon after the death of his wife (Bridget Moynahan)–the woman whose love inspired him to retire from his life as an expert assassin–Wick receives an unwelcome visit to his minimalist, modern mansion in the middle of the night. Russian bad guys have come to steal his prized 1969 Mustang–and they kill his dog in the process. The latter act is horrifying in itself; what’s even worse is that the adorable beagle puppy, Daisy, was a posthumous gift to John from his dying wife, who knew he’d need someone else to love.

(Moynahan’s character, by the way, is barely even a person. She’s an image on a smartphone video clip–a body lying in a hospital bed, suffering from an unspecified disease. She’s an idea. But her loss provides Wick with a melancholy that lingers over his demeanor and every decision he makes.)

Wick wastes no time unearthing his stashed arsenal and seeking revenge. It turns out that the group’s reckless, young leader, Iosef (Alfie Allen), is the son of a former associate of Wick’s: mob boss Viggo Tarasov (a sophisticated but scary Michael Nyqvist), who is fully aware of Wick’s killing capacity. Also in the mix is Willem Dafoe as an expert sniper who may or may not be on Wick’s side. Once the premise is established in the script from Derek Kolstad, it’s scene after scene of Wick taking out entire rooms full of people who are foolish enough to stand in his way. This is not exactly a complicated genre from a narrative perspective.

But directors Chad Stahelski and David Leitch–who work as a filmmaking team, although Leitch technically takes producing credit–are both veteran stuntmen who clearly know what they’re doing when it comes to this kind of balletic action. Stahelski got his break 20 years ago when he served as a stunt double following Brandon Lee’s deadly accident while shooting “The Crow” and went on to perform as Reeves’ stunt double in “The Matrix” trilogy. Leitch’s work includes doubling for Brad Pitt (in “Fight Club” and “Mr. and Mrs. Smith”) and Matt Damon (in “The Bourne Ultimatum”).

All those years of experience and exposure give their film a level of confidence you don’t ordinarily see in first-time directors. They’re smart enough to let the intricate choreography speak for itself. They let the fight scenes play out without relying on a lot of nauseating shaky-cam or Cuisinart edits, which sadly have become the aesthetic standard of late.

But beyond the exquisite brutality they put on display, they’ve also got an eye for artistry, with cinematographer Jonathan Sela helping convey an ominous sense of underworld suspense. Early scenes are so crisply desaturated, they look black and white, from the cloudy, rainy skies over Wick’s wife’s funeral to his head-to-toe wardrobe to his sleek, slate-gray Mustang. As Wick begins to re-immerse himself in the criminal world he’d escaped, other scenes pop in their vibrancy–the deep green of a secret, members-only cocktail bar, or the rich red of a Russian bad guy’s shirt under an impeccably tailored suit.

While the body count grows numbing and repetitive, “John Wick” actually is more compelling in the aesthetically heightened, specifically detailed world it depicts. It’s the New York City of the here and now, but Wick, his fellow assassins and other sundry nefarious sorts occupy their own parallel version of it, with its own peculiar rules which almost seem quaint. They have their own currency: gold coins reminiscent of pirates’ doubloons, which can be used for goods and services or just as thanks for a favor. And they frequent an upscale, downtown hotel and bar called The Continental (Lance Reddick from “The Wire” is the unflappably polite manager), a sort of safe zone where protocol dictates that peace prevails, and where killing is cause for dismissal. The courtliness of it all provides an amusing and welcome contrast to the non-stop carnage.

You can check out any time you’d like, it seems, but you can never leave.