Thomas Jefferson fathered six children by his wife, Martha, and, according to revisionist historians, several more by his slave Sally Hemings. Yet if you visit his home at Monticello, outside Charlottesville in Virginia, you will come away with the impression that he was a bachelor. Everything is arranged for a single man, including the bed, barely large enough for one, and the toys: adjustable chairs and desks, ingenious writing instruments, closets that seem to hang their own clothes and staircases that (in an era of grand flights of stairs) are wide enough for only one person at a time.

After the guide has told you about Jefferson’s first marriage, and his deathbed promise to Martha that he would never marry again, you wait for Sally Hemings’ name to be mentioned, but it never is. If you ask about her, your guide will explain that there is no definitive evidence that Jefferson ever had children by Hemings.

Of course the chances that Jefferson would leave such definitive evidence are minute, and in a state where slaves had no legal standing except as property, there was no way for them to do it. So we are left with the debate between the traditional historians and people who say they are Jefferson’s black descendants.

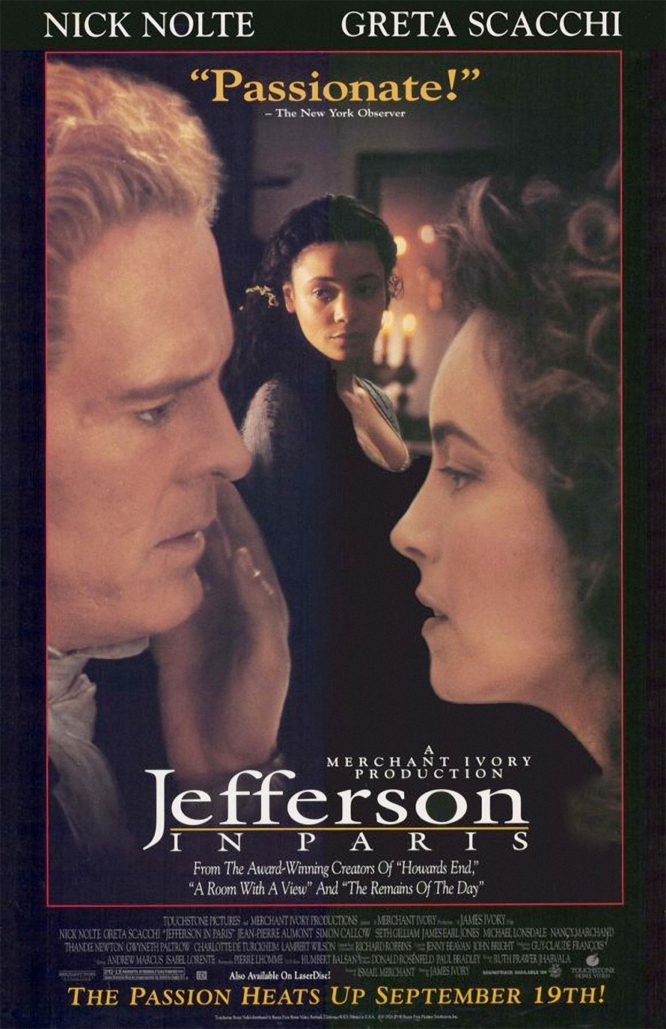

“Jefferson in Paris,” the new film by the team of Ismail Merchant, James Ivory and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, has no doubt that Jefferson fathered at least one child by Sally Hemings. What the movie doesn’t know is what, if anything, he thought about it. The Jefferson in this movie is such a remote figure that you wonder, by the movie’s end, if he actually knew he was having sex at the time.

Perhaps his mind was preoccupied with architecture or philosophy.

The movie takes place in the mid-1780s, when Jefferson (Nick Nolte), author of the Declaration of Independence, replaced Benjamin Franklin as the representative of the new United States at the court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. His wife is already dead. He lives the life of a man about town, carrying on a flirtation with Maria Cosway (Greta Scacchi), the beautiful wife of a world-class fop (Simon Callow). If she leaves her husband, will he marry her? She asks about the deathbed promise, and he regards her solemnly and says, “You and I are alive, and the earth belongs to us, to the living.” Ah, yes, but that doesn’t answer her question, and there seems something considered and remote about his passion, as if his mind were elsewhere.

Jefferson’s oldest daughter, Patsy (Gwyneth Paltrow), is in Paris with him. Another of his daughters dies in Virginia, and he sends for his youngest, Polly (Estelle Eonnet), to join him. With her comes her young slave Sally Hemings (Thandie Newton, from “Flirting“), a quadroon who was his late wife’s half-sister on, needless to say, her father’s side.

Sally is only 15 when she arrives in Paris. Soon Jefferson is making her little presents, such as a necklace, and she is visiting him in his bedroom for flighty flirtations. Their closeness is obvious to Patsy, who calls it “unspeakable,” and eventually Maria sees enough to realize her own future with Thomas is limited.

Still, considering that the relationship of slave and master is really the reason “Jefferson in Paris” was made, the filmmakers seem to have few ideas about the nature of their feelings. Does Sally “love” Jefferson, or only act seductively around him because of his importance and power? How does he feel about her? She is pregnant by the end of the film, but the sex scene is off-camera, and later as he discusses Sally’s plight, Jefferson seems to talk almost as if she might have gotten pregnant by herself. Newton’s performance is also hard to read; she adopts an odd dialect, behaves childishly, seems more like a caricature of an ingratiating slave than like a woman who apparently interested Jefferson so much that he went on to have several more children with her over a period of years.

Of course the Sally Hemings matter is only a part of the film. We also get glimpses of the decadence of the French court (Marie Antoinette appearing in bizarre theatricals). There are discussions about the politics of the time, including several about slavery, in which Jefferson seems confused about exactly what he thinks: It is bad, yes, but then it is the law, although of course it should not be the law . . .

Sally Hemings’ brother James (Seth Gilliam) is also part of the household, and quite aware that under French law he is a free man. Jefferson therefore pays James and Sally salaries (“Yours to do with as you wish,” he tells her; “would you like me to keep it for you?”). When Jefferson offers James and Sally their choice of freedom or returning to Monticello, Sally cries: “Where’s I going?” The implication is that the paternalistic Jefferson thinks they’ll be better off staying with him, “the best master in Virginia,” according to his daughter. (James Hemings’ confrontations with Jefferson and Sally are the best-written scenes in the film; the character seems willing to confront questions that the movie otherwise allows to slip quietly past.) The film is lavishly produced and visually splendid, like all the Merchant-Ivory productions (“Howards End,” “The Remains of the Day”). But what is it about? Revolution? History? Slavery? Romance? No doubt a lot of research and speculation went into Jhabvala’s screenplay, but I wish she had finally decided to jump one way or the other. The movie tells no clear story and has no clear ideas; it is all elaborate glimpses of a private man who, as the architect of his own home, did not see why anyone would ever want to walk upstairs side-by-side.