The characters in “High Hopes” exist on either side of the great divide in Margaret Thatcher’s England, between the new yuppies and the die-hard socialists.

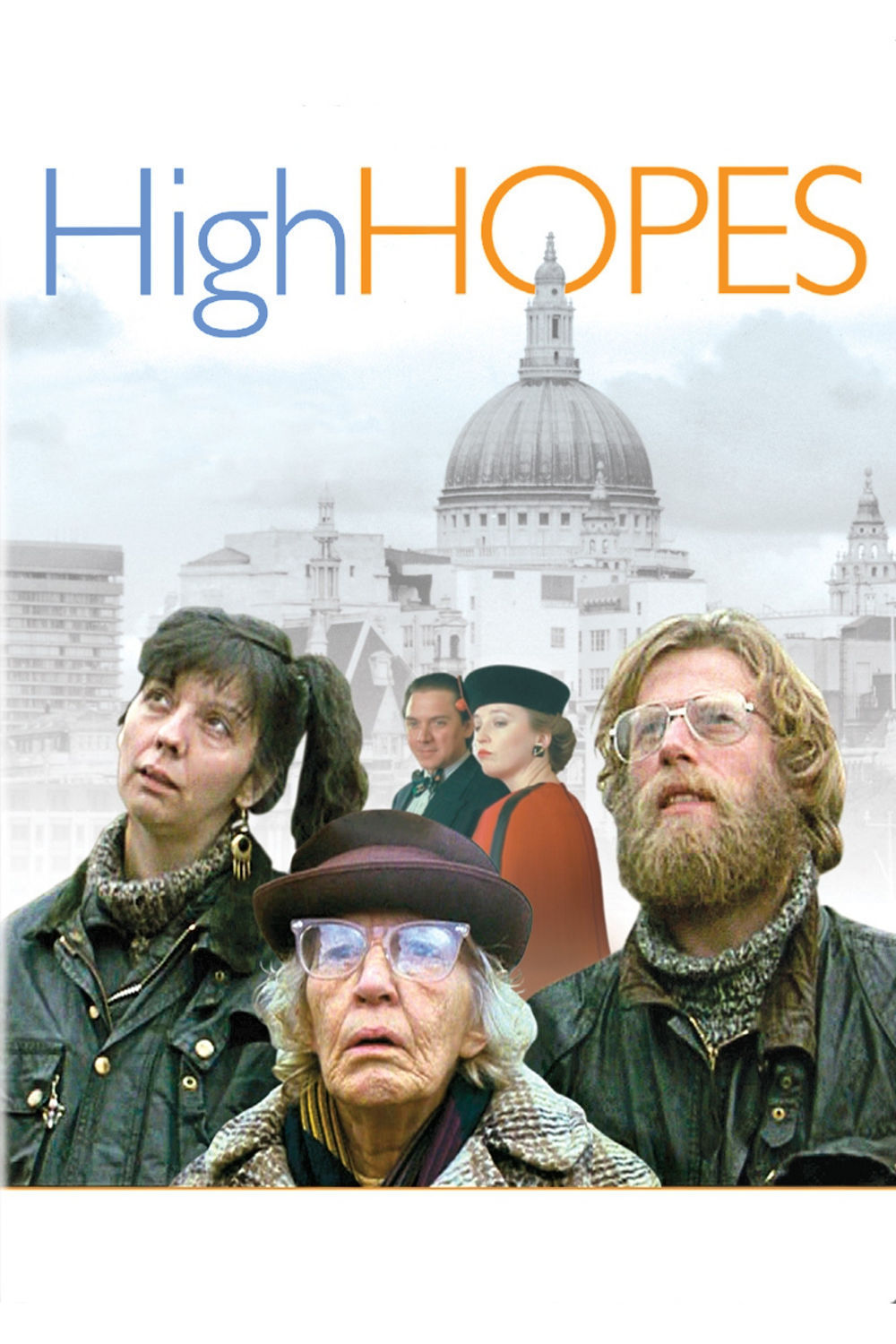

Cyril and Shirley, quasi-hippie survivors of the 1970s, live in comfortable poverty in a small flat, supported by Cyril’s earnings as a motorcyle messenger. Cyril’s sister, Valerie, lives in an upscale neighborhood surrounded by Modern Conveniences with her husband, Martin, who sells used cars. In their language, their values and the way they furnish their lives, each couple serves as a stereotype for their class: Cyril and Shirley are what Tories think lefists are like, and Valerie and Martin stand for all the left hates most about Thatcherism.

Sometimes these two extremes literally live next door to each other. Cyril and Valerie’s mother, a bitter, withdrawn old woman named Mrs. Bender, lives in solitude in the last council flat on a street that has otherwise been gentrified. Her next-door neighbors are two particularly frightening examples of the emerging social class the British call Hooray Henrys (and Henriettas). Paralyzed by their affected speech and gestures, they play out a grotesque parody of upper-class life in their own converted row house, which they like to forget was recently public housing for the poor.

All of these lives, and a few others, collide during the course of a few days in “High Hopes,” which was written and directed by Mike Leigh with the participation of the actors, who developed their scenes and dialogue in improvisational sessions. Leigh is a legendary figure in modern British theater for his plays and television films that mercilessly dissect the British class system, using as their weapon the one emotion the British fear most, embarrassment.

Leigh has made only one other film, the brilliant “Bleak Moments,” some 18 years ago. He cannot easily find financing for his films because, at the financing stage, they do not yet have scripts; he believes in developing the material as he goes along. The backing for “High Hopes” came partly from Channel Four, the innovative alternative British TV channel, and with its money he has produced one of those rare films in which anger and amusement exist side by side – in which the funniest scenes are also the most painful ones.

Consider, for example, the dilemma of the old mother, Mrs. Bender, when she locks herself out of her council house. She naturally turns for help to her neighbors. But Rupert and Laetitia, who live next door, are yuppies who treat the poor as a disease they hope not to catch. As the old woman stands helplessly at the foot of the steps, grasping her shopping cart, her chic neighbor supposes she must, after all, give her shelter, and says “Hurry up, now. Chop, chop!” Mrs. Bender calls her daughter, Valerie, who can hardly be bothered to come and help her, until she learns that her mother is actually inside the yuppie house next door. Then she’s there in a flash, hoping to nose about and see what they’ve “done” with the place. Some of her dialogue almost draws blood, as when she looks into Rupert’s leather-and-brass den, and shouts, “Mum, look what they’ve done with your coal hole!” This sort of materialism and pride in possessions is far from the thoughts of Cyril and Shirley, the left-wing couple, who still sleep on a mattress on the floor and decorate their flat with posters and cacti. Lacking in ambition, they make enough from Cyril’s messenger job to live on, and they smooth over the rough places with hashish.

They are kind, and the movie opens with them taking a bewildered mental patient into their home; he has been wandering the streets of London, a victim of Thatcher’s dismantled welfare state. (America and Britain are indeed cousins across the waters; we are reminded that the Reagan administration benevolently turned thousands of our own mentally ill out onto the streets.) Most of the action in “High Hopes” centers on two set pieces, both involving the mother: the crisis of the lost keys, and then the mother’s birthday party, which the hysterical Valerie stages as a parody of happy times. As the confused Mrs. Bender sits in bewilderment at the head of the table, her daughter shouts encouragement at her with a shrill desperation. The evening ends with a bitter quarrel between the daughter and her husband, while Cyril and Shirley pack the miserable old lady away home.

“High Hopes” is not a movie with a simple message; it’s not left-wing propaganda in which all kindness resides with the Labourites and all selfishness with the Conservatives. Leigh shows us a London that exists beyond such easy distinctions, and it is possible he is almost as angry at Cyril and Shirley – laid-back, gentle, ineffectual potheads – as at the movie’s cruel upward-strivers.

Much of the movie’s concern seems to center on Shirley’s desire to have a child, and Cyril’s desire that they should not. Their conflict is not the familiar old one of whether to “bring” a child into “this world.” It seems to center more on the core of Cyril’s laziness.

He cannot be bothered. Of course, he stands for all good things and opposes all bad ones in principle, but in practice, it’s simpler to light up a joint.

“High Hopes” is an alive and challenging film, one that throws our own assumptions and evasions back at us. Leigh sees his characters and their lifestyles so vividly, so mercilessly and with such a sharp satirical edge, that the movie achieves a neat trick: We start by laughing at the others, and end by feeling uncomfortable about ourselves.