Stanley Kubrick considered “The Killing” (1956) to be his first mature feature, after a couple of short warm-ups. He was 28 when it was released, having already been an obsessed chess player, a photographer for Look magazine and a director of “March of Time” newsreels. It’s tempting to search here for themes and a style he would return to in his later masterpieces, but few directors seemed so determined to make every one of his films an individual, free-standing work. Seeing it without his credit, would you guess it was by Kubrick? Would you connect “Dr. Strangelove” with “Barry Lyndon?”

This is a heist movie. Like horror films, heists are a genre that make stars not so necessary. The durable form inspires directors to create plots that are baffling in their complexity or bold in their simplicity. In “Bonnie and Clyde,” the gang parks in front of a bank, walks in with guns, and walks out (in theory) with the loot. In David Mamet’s “Heist,” the characters are involved in interlocking levels of cons being pulled on each other. In “Rififi,” a theft involves a plan of almost unnecessary acrobatic ingenuity. Kubrick’s plan here for a race track robbery involves two of those plot aspects; not so much the acrobatics. His narrative approach seems blunt, but the narrative itself is so labyrinthine we abandon any hope of trying to piece it together and just abandon ourselves to letting it happen. We feel in safe hands.

Perhaps a motif can be found in the movie’s storefront chess club which, I learn, Kubrick frequented as a kid. His gang leader Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden) goes there to meet a professional wrestler named Maurice, played by a professional wrestler named Kola Kwariani. Maurice is big and strong and is needed to start a fight at the race track bar to divert attention during the heist. Like all the members of Johnny’s team, he has no idea of the overall plot. He just knows his role and his payoff, and knows Johnny enough to trust him.

The game of chess involves holding in your mind several alternate possibilities. The shifting of one piece can result in a radically different game. Johnny Clay has devised a strategy seemingly as flawless as Bobby Fischer’s “Perfect Games,” but it depends on all the players making the required moves on schedule. If a piece shifts, everything changes, a possibility Johnny should have given more thought to.

The movie is narrated in an exact, passionless voice by the uncredited Art Gilmore, a veteran radio announcer. He places great emphasis on precise dates and times of day, although really only one day and time are crucial–4 p. m., the starting time of a $100,000 high stakes horse race. The rest of his narration serves only to confirm what we can see for ourselves, that the events on screen are not happening in chronological order. The plot jumps around like a chess player’s mind: “If he does this, and I do that, and then he..”

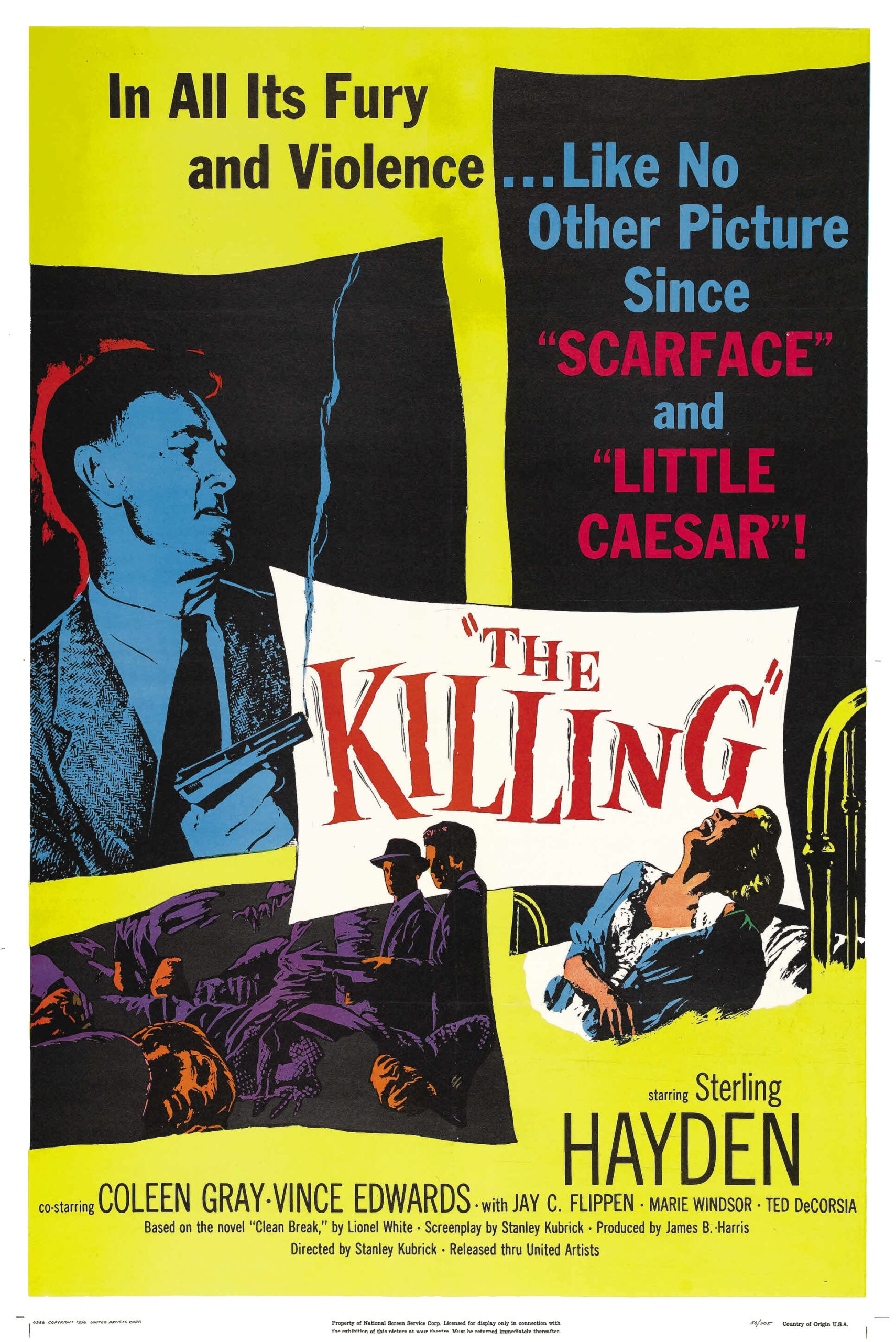

In the few days before the heist, Johnny makes the rounds of his team members. We meet them at the same time. There’s a large cast, made easy to follow because of typecasting and the familiar faces of many supporting players. Let’s see. In no particular order (which would please the narrator), there are Fay (Coleen Gray), Johnny’s girl; Marvin Unger (Jay C. Flippen), an old friend who is putting up the cost of the operation; Randy Kennan (Ted de Corsia), a crooked cop; Sherry Peatty (Marie Windsor), a gold-digging floozy; her husband George Peatty (Elisha Cook), a weakling race track cashier who hopes to buy her affection; Val Cannon (Vince Edwards), Sherry’s actual lover; Mike O’Reilly (Joe Sawyer), the racetrack bartender who needs money for his sick wife; Nikki Arcane (Timothy Carey), a rifle sharpshooter; Leo the Loan shark (Jay Adler), and assorted others. Kubrick brings all these types onscreen, makes it clear who they are and sees that we will remember them, while only gradually revealing their roles in the heist.

Filmed largely in San Mateo and Venice, Calif., and at the Bay Meadows Racetrack, the movie has the look and feel of glorious 1950s black and white film noir. On a budget of $230,000, Kubrick uses a lot of actual locations. We see a shabby motel with residential rooms by the week or month, the low-rent “luxury” of the Peatty’s apartment, the sun-washed streets. Many heist movies feature a chalk talk in which the leader explains the scenario to his gang so that we can visualize it; Jean-Pierre Melville’s version of this scene adds immeasurably to “Bob le Flambeur.” Kubrick puts his pieces in place but only when the actual plan is underway do we understand them. We go in like a chess player who knows what the Rook, Knight and Queen do, but doesn’t know what will happen in the game. Nor, it turns out, do they all know the rules.

I wouldn’t think of giving away the game. The writing and editing are the keys to how this film never seems to be the deceptive assembly that it is, but appears to be proceeding on schedule, whatever that schedule is. We accept even action that makes absolutely no sense, as in a crucial moment involving Nikki the sharpshooter. Required to hit a moving target with a rifle with telescopic sights, he inexplicably parks his sports car, a convertible with the top down, in plain view in a parking lot so that anyone can see him take out the rifle, aim and fire. In theory they’re looking elsewhere. In practice his personality gets him in trouble.

Sterling Hayden was a considerable screen presence with his tough guy face and his pouting lower lip. His gravel voice lays out instructions and requirements in a flat, factual manner; his gang members take them at face value. He never displays much emotion, not even at the end, when a great deal might be justified. We don’t see passion, fear, greed. He could be a chess player in the Zone. He has a streak of nihilism. The most colorful players are Marie Windsor, famously known as Marie Windsor, and Elisha Cook, famous for playing milquetoasts and chumps in the movies of four decades. She wraps him around her little finger, and he comes back for more.

Considering that it cheerfully abandons any attempt at chronological suspense, “The Killing” is an unreasonable success. The prize will be $2 million–the day’s expected total receipts at the track. This heist is worth a lot of planning, and Johnny has gone the distance. In his mind his plan is superb. All it depends upon is everybody doing exactly what is required of them, exactly when and where. The word that occurs to me in describing Kubrick’s approach to Johnny and the film, is “control.” That may suggest the link between this first mature feature and Kubrick’s later films, so varied and brilliant.

In his films, he had the plan in his mind. He knew where everyone should be and what they should do. Such a perfectionist was Kubrick that he knew every theater his films were opening in, and the daily grosses. It’s said that a projectionist in Kansas City received a phone call from Kubrick in England, informing him that the picture was out of focus. Is that story apocryphal? I’ve never thought so.

“The Killing” is streaming on Netflix Instant. Also in my Great Movies Collection: Reviews of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Dr. Strangelove,” “Barry Lyndon,” “Paths of Glory” and “The Shining.”