Stanley Kubrick’s “Barry Lyndon,” received indifferently in 1975, has grown in stature in the years since and is now widely regarded as one of the master’s best. It is certainly in every frame a Kubrick film: technically awesome, emotionally distant, remorseless in its doubt of human goodness. Based on a novel published in 1844, it takes a form common in the 19th century novel, following the life of the hero from birth to death. The novel by Thackeray, called the first novel without a hero, observes a man without morals, character or judgment, unrepentant, unredeemed. Born in Ireland in modest circumstances, he rises through two armies and the British aristocracy with cold calculation.

“Barry Lyndon” is aggressive in its cool detachment. It defies us to care, it asks us to remain only observers of its stately elegance. Many of its developments take place off-screen, the narrator informing us what’s about to happen, and we learn long before the film ends that its hero is doomed. This news doesn’t much depress us, because Kubrick has directed Ryan O'Neal in the title role as if he were a still life. It’s difficult to imagine such tumultuous events whirling around such a passive character. He loses a fortune, a wife or a leg with as little emotion as he might in losing a dog. Only the death of his son devastates him and that perhaps because he sees himself in the boy.

The casting choice of O’Neal is bold. Not a particularly charismatic actor, he is ideal for the role. Consider Albert Finney in “Tom Jones,” for example, bursting with vitality. Finney could not possibly have played Lyndon. O’Neal easily seems self-pitying, narcissistic, on the verge of tears. As one terrible event after another occurs to him, he projects an eerie calm. Nor do his triumphs — in gambling, con games, a fortunate marriage and even acquiring a title — seem to bring him much joy. He is a man to whom things happen.

The other characters seem cast primarily for their faces and their presence, certainly not for their personalities. Look at the curling sneer of the lips of Leonard Rossiter, as Captain Quin, who ends Barry’s youthful affair with a cousin by an advantageous offer of marriage. Study the face of Marisa Berenson, as Lady Lyndon. Is there any passion in her marriage? She loves their son as Barry does, but that seems to be their only feeling in common. When the time comes for her to sign an annuity check for the man who nearly destroyed her family, her pen pauses momentarily, then smoothly advances.

The film has the arrogance of genius. Never mind its budget or the perfectionism in its 300-day shooting schedule. How many directors would have had Kubrick’s confidence in taking this ultimately inconsequential story of a man’s rise and fall, and realizing it in a style that dictates our attitude toward it? We don’t simply see Kubrick’s movie, we see it in the frame of mind he insists on — unless we’re so closed to the notion of directorial styles that the whole thing just seems like a beautiful extravagance (which it is). There is no other way to see Barry than the way Kubrick sees him.

Kubrick’s work has a sense of detachment and bloodlessness. The most “human” character in “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968) is the computer, and “A Clockwork Orange” (1971) is disturbing specifically in its objectivity about violence. The title of “Clockwork,” from Anthony Burgess’ novel, illustrates Kubrick’s attitude to his material. He likes to take organic subjects and disassemble them as if they were mechanical. It’s not just that he wants to know what makes us tick; he wants to demonstrate that we do all tick. After “Spartacus” (1960), he never again created a major character driven by idealism or emotion.

The events in “Barry Lyndon” could furnish a swashbuckling romance. He falls into a foolish adolescent love, has to leave his home suddenly after a duel, enlists almost accidentally in the British army, fights in Europe, deserts from not one but two armies, falls in with unscrupulous companions, marries a woman of wealth and beauty, and then destroys himself because he lacks the character to survive.

But Kubrick examines Barry’s life with microscopic clarity. He has the confidence of the great 19th century novelists, authors who stood above their material and accepted without question their right to manipulate and interpret it with omniscience. Kubrick has appropriated Thackeray’s attitude — or Trollope’s or George Eliot’s. There isn’t Dickens’ humor or relish of human character. Barry Lyndon, falling in and out of love and success, may see no pattern in his own affairs, but the artist sees one for him, one of consistent selfish opportunism.

Perhaps Kubrick’s buried theme in “Barry Lyndon” is even similar to his outlook in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Both films are about organisms striving to endure and prevail — and never mind the reason. The earlier film was about the human race itself; this one is about a depraved minor example of it. Barry journeys without plan, sees what he desires, tries to acquire it and perhaps succeeds because he plays roles so well without being remotely dedicated to them. He looks the part of a lover, a soldier, a husband. But there is no there there.

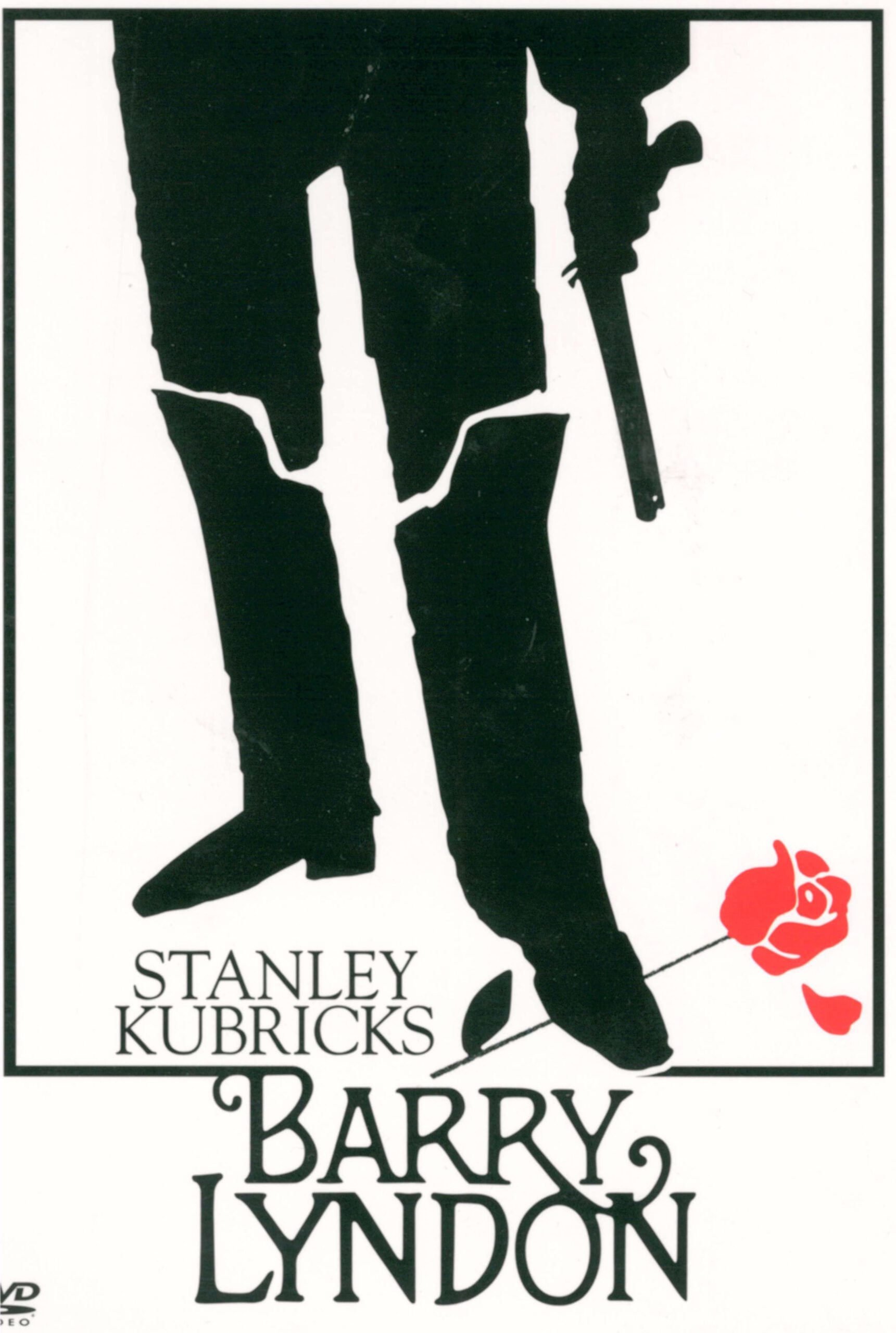

There’s a sense in both this film and “2001” that a superior force hovers above these struggles and controls them. In “2001,” it was a never-clarified form of higher intelligence. In “Barry Lyndon,” it’s Kubrick himself, standing aloof from the action by two distancing devices: the narrator (Michael Hordern), who deliberately destroys suspense and tension by informing us of all key developments in advance, and the photography, which is a succession of meticulously, almost coldly, composed set images. It’s notable that three of the film’s four Oscars were awarded for cinematography (John Alcott), art direction (Ken Adam) and costumes (Ulla-Britt Soderlund and Milena Canonero). The many landscapes are often filmed in long shots; the fields, hills and clouds could be from a landscape by Gainsborough. The interior compositions could be by Joshua Reynolds.

This must be one of the most beautiful films ever made, and yet the beauty isn’t in the service of emotion. Against magnificent settings, the characters play at intrigues and scandals. They cheat at cards and marriage, they fight ridiculous duels. This is a film with a backdrop of the Seven Years’ War that engulfed Europe, and it hardly seems to think the war worth noticing, except as a series of challenges posed for Barry Lyndon. By placing such small characters on such a big stage, by forcing our detachment from them, Kubrick supplies a philosophical position just as clearly as if he’d put speeches in his characters’ mouths.

The images proceed in elegant stages through the events, often accompanied by the inexorable funereal progression of Handel’s “Sarabande.” For such an eventful life, there is no attempt to speed the events along. Kubrick told the critic Michel Ciment he used the narrator because the novel had too much incident even for a three-hour film, but there isn’t the slightest sense he’s condensing.

Some people find “Barry Lyndon” a fascinating, if cold, exercise in masterful filmmaking; others find it a terrific bore. I have little sympathy for the second opinion; how can anyone be bored by such an audacious film? “Barry Lyndon” isn’t a great entertainment in the usual way, but it’s a great example of directorial vision: Kubrick saying he’s going to make this material function as an illustration of the way he sees the world.