The rock opera “Pink Floyd: The Wall,” first performed in 1978, came at a time when some rock artists were taking themselves very seriously indeed. While the Beatles and Stones had recorded stand-alone songs or themed albums at the most, The Who produced “Tommy” in 1969 and “Quadrophenia” in 1973. David Bowie and Genesis followed, and “Pink Floyd: The Wall” essentially brought a close to that chapter.

This isn’t the most fun to listen to and some viewers don’t find it to much fun to watch, but the 1982 film is without question the best of all serious fiction films devoted to rock. Seeing it now in more timid times, it looks more daring than in did in 1982, when I saw it at Cannes. Alan Parker, a director who seemed to deliberately choose widely varied projects, here collaborates with Gerald Scarfe, a biting British political caricaturist, to make what is essentially an experimental indie. It combines wickedly powerful animation with a surrealistic trip through the memory and hallucinations of an overdosing rock star. It touches on sex, nuclear disarmament, the agony of warfare, childhood feelings of abandonment, the hero’s deep unease about women, and the life style of a rock star at the end of his rope.

What it doesn’t depict is rock performance. There are no actual concert scenes, although there are groupies and limousines and a personal manager. Or perhaps there are concert scenes, and they’re disguised as an extended portrait of a modern fascist dictator whose fans morph into an adoring populace. I don’t believe this dictator is intended as a parallel to any obvious model like Hitler or Stalin; he seems more a fantasy of Britain’s own National Socialists led by Oswald Mosley.

“Pink Floyd: The Wall” was written almost entirely by Roger Waters, the band’s intellectual, self-analytical, sometimes tortured lead singer. Its central character, named Pink, is played by Bob Geldof, of all people, who could not be less like Pink. The credits say he is being “introduced.” He’s onscreen more than anyone else, goes through punishing scenes, and even sings at times, although this isn’t a performance film but essentially a 95-minute music video. Geldof morphs through several standard rock star looks, all familiar from other stars: The big-haired sex god, the attractive leading man, the haunted neurotic, the cadaverous drug victim. In his most agonizing scene, he shaves off all his body hair in a bloody reprise of Scorsese’s famous short “The Big Shave.”

There’s also a scene where he trashes a hotel room; he must have carefully studied the room destruction in “Citizen Kane.” The scene involves a terrified groupie (Jenny Wright) who flees around the room and cowers behind furniture but inexplicably doesn’t flee immediately into the corridor. More frightening is that although Pink narrowly misses her with a wine bottle and a piece of furniture, he doesn’t seem really aware that she’s there.

The girl is earlier portrayed as concerned about him, and rather sweet. That sets her aside from the other females in the movie. There is Pink’s mother, so devastated by her husband’s death in war that she becomes smothering and domineering toward her son. Then Pink’s wife, alienated by his zombie-like disconnection from life, turning finally to an anti-war lecturer to cheat with a man who cares about something. These are both at least recognizable women. The most grotesque female figure in the film is created by Scarfe’s animation.

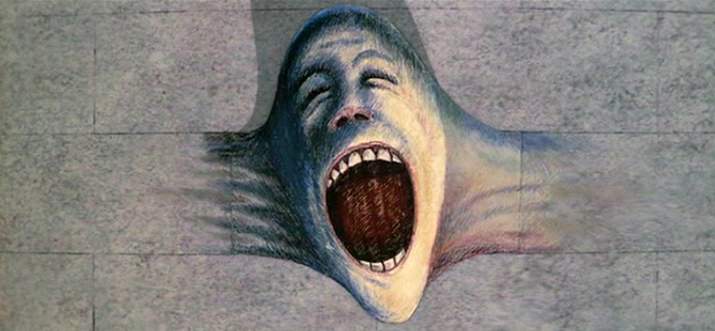

This is a flower so gynecological that Georgia O’Keefe might have been appalled. The bloom seduces a male flower, ravishes him, plunders him, and ultimately devours him. Perhaps she reflects Pink’s terror of castration. Scarfe distorts the flower into other shapes for disquieting transformations, as a dove becomes a screaming eagle and then a warplane, landscapes are devastated and walls and goose-stepping hammers march across the land.

As you have gathered, I’m not describing what we think of as a “musical.” This is a bold, relentless visualization of Waters’ despair. It incorporates a theme that resonates with British audiences, an educational system ruled by stern, kinky headmasters. The opera’s most famous song becomes its best scene. As Parker visualizes “Another Brick in the Wall,” students on a conveyor belt are fed into blades that extrude them as ground meat. In the process, the students lose their faces behind blank masks, which are seen again in the faces of the dictator’s followers. Message: Education produces mindless creatures suitable as cannon fodder or the puppets of fascists. I gather Waters wasn’t keen on attending the reunions of his old school.

There is a narrative, although “Pink Floyd: The Wall” doesn’t underline it. It suggests that Pink has vivid images of his father’s ordeal under fire, is raised too protectively, was incapable of a successful marriage, took no pleasure in casual sex, and finally disappeared into psychological catatonia under the influence of drugs. The opening scene returns later, suggesting all of the action in the film takes place in Pink’s head in that hotel room in more or less the film’s running time.

The best audience for this film would be one familiar with filmmaking techniques, alert to directorial styles, and familiar with Roger Waters and Pink Floyd. I can’t imagine a “rock fan” enjoying it very much on first viewing, although I know it has developed a cult following. It’s disquieting and depressing and very good. No one much enjoyed making it. I remember Alan Parker being somewhat quizzical at the time; I learn from Wikipedia that he fought with Waters and Scarfe and considered the film “one of the most miserable experiences of my creative life.” Waters’ own verdict: “I found it was so unremitting in its onslaught upon the senses, that it didn’t give me, anyway, as an audience, a chance to get involved with it.”

So it’s difficult, painful and despairing, and its three most important artists came away from it with bad feelings. Why would anybody want to see it? Perhaps because filming this material could not possibly have been a happy experience for anyone — not if it’s taken seriously. I believe Waters wrote out of the dark places in his soul, fueled by his contempt for rock stars in general, himself in particular, and their adoring audiences. He was, in short, composing not as an entertainer but as an artist. Sir Alan Parker is a cheerful man, although not without a temper, and there is no apparent thread to connect this film with his credits such as “The Commitments,” “Fame,” “Bugsy Malone” or even such heavier films as “Shoot the Moon” and “Angela's Ashes.” I can’t say I really know Parker, but I’ve spent enough time around him to sense he wasn’t congenitally drawn to this material.

Those tensions and conflicts produced, I believe, the right film for this material. I don’t require that its makers had a good time. I’m reminded of my favorite statement by Francois Truffaut: “I demand that a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema. I am not at all interested in anything in between.”