In 1929, the year it was released, films had an average shot length (ASL) of 11.2 seconds. “Man With a Movie Camera” had an ASL of 2.3 seconds. The ASL of Michael Bay’s “Armageddon” was — also 2.3 seconds. Why would I begin a discussion of a silent classic by discussing such a mundane matter? It helps to understand the impact the film made at the time. Viewers had never seen anything like it, and Mordaunt Hall, the horrified author of the New York Times review, wrote: “The producer, Dziga Vertof, does not take into consideration the fact that the human eye fixes for a certain space of time that which holds the attention.” This reminds me of Harry Carey’s advice in 1929 to John Wayne, as the talkies were coming in: “Stop halfway through every sentence. The audience can’t listen that fast.”

“Man With a Movie Camera” is fascinating for many better reasons than its ASL, but let’s begin with the point Dziga Vertof was trying to make. He felt film was locked into the tradition of stage plays, and it was time to discover a new style that was specifically cinematic. Movies could move with the speed of our minds when we are free-associating, or with the speed of a passionate musical composition. They did not need any dialogue–and indeed, at the opening of the film he pointed out that it had no scenario, no intertitles, and no characters. It was a series of images, and his notes specified a fast-moving musical score.

There was an overall plan. He would show 24 hours in a single day of a Russian city. It took him four years to film this day, and he worked in three cities: Moscow, Kiev and Odessa. His wife Yelizaveta Svilova supervised the editing from about 1,775 separate shots — all the more impressive because most of the shots consisted of separate set-ups. The cinematography was by his brother, Mikhail Kaufman, who refused to ever work with him again. (Vertov was born Denis Kaufman, and worked under a name meaning “spinning top.” Another brother, Boris Kaufman, immigrated to Hollywood and won an Oscar for filming “On the Waterfront.”)

Born in 1896 and coming of age during the Russian Revolution, Vertov considered himself a radical artist in a decade where modernism and surrealism were gaining stature in all the arts. He began by editing official newsreels, which he assembled into montages that must have appeared rather surprising to some audiences, and then started making his own films. He would invent an entirely new style. Perhaps he did. “It stands as a stinging indictment of almost every film made between its release in 1929 and the appearance of Godard’s ‘Breathless’ 30 years later,” the critic Neil Young wrote, “and Vertov’s dazzling picture seems, today, arguably the fresher of the two.” Godard is said to have introduced the “jump cut,” but Vertov’s film is entirely jump cuts.

There is a temptation to review the simply by listing what you will see in it. Machinery, crowds, boats, buildings, production line workers, streets, beaches, crowds, hundreds of individual faces, planes, trains, automobiles, and so on. But these shots have an organizing pattern. “Man With a Movie Camera” opens with an empty cinema, its seats standing at attention. The seats swivel down (by themselves), and an audience hurries in and fills them. They begin to look at a film. This film. And this film is about–this film being made.

The only continuing figure — not a “character” — is the Man With the Movie Camera. He uses an early hand-cracked model, smaller than the one Buster Keaton uses in “The Cameraman” (1928), although even that one is light enough to be balanced on the shoulder with its tripod. This Man is seen photographing many of the shots in the movie. Then there are shots of how he does it–securing the tripod and himself to the top of an automobile or the bed of a speeding truck, stooping to walk through a coal mine, hanging in a basket over a waterfall. We see a hole being dug between two train tracks, and later a train racing straight towards the camera. We’re reminded that when the earliest movie audiences saw such a shot, they were allegedly terrified, and ducked down in their seats.

Intercut with this are shots of this film being edited. The machinery. The editor. The physical film itself. Sometimes the action halts with a freeze frame, and we see that the editor has stopped work. But that’s later–placing it right after the freeze frame would seem too much like continuity. If there is no continuity, there is a gathering rhythmic speed that reaches a crescendo nearer the end. The film has shot itself, edited itself, and now is conducting itself at an accelerating tempo.

Most movies strive for what John Ford called “invisible editing” — edits that are at the service at the storytelling, and do not call attention to themselves. Even with a shock cut in a horror film, we are focused on the subject of the shot, not the shot itself. Considered as a visual object, “Man With a Movie Camera” deconstructs this process. It assembles itself in plain view. It is about itself, and folds into and out of itself like origami. It was in 1912 that Marcel Duchamp shocked the art world with his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase.” It wasn’t shocked by nudity–the painting was too abstract to show any. They were shocked that he depicted the descent in a series of steps taking place all at the same time. In a way, he had invented the freeze frame.

What Vertov did was elevate this avant-garde freedom to a level encompassing his entire film. That is why the film seems fresh today; 80 years later, itisfresh. There had been “city documentaries” earlier, showing a day in the life of a metropolis; one of the most famous was “Berlin: Symphony of a Great City” (1927).

By filming in three cities and not naming any of them, Vertov had a wider focus: His film was about The City, and The Cinema, and The Man With a Movie Camera. It was about the act of seeing, being seen, preparing to see, processing what had been seen, and finally seeing it. It made explicit and poetic the astonishing gift the cinema made possible, of arranging what we see, ordering it, imposing a rhythm and language on it, and transcending it. Godard once said “The cinema is life at 24 frames per second.” Wrong. That’s what life is. The Cinema only starts with the 24 frames — and besides, in the silent era it was closer to 18 fps. It’s what you doafteryou have your frames that makes it Cinema.

The experience of “Man With a Movie Camera” is unthinkable without the participation of music. Virtually every silent film was seen with music, if only from a single piano, accordion, or violin. The Mighty Wurlitzer, with its sound effects and different musical voices, was invented for movies.

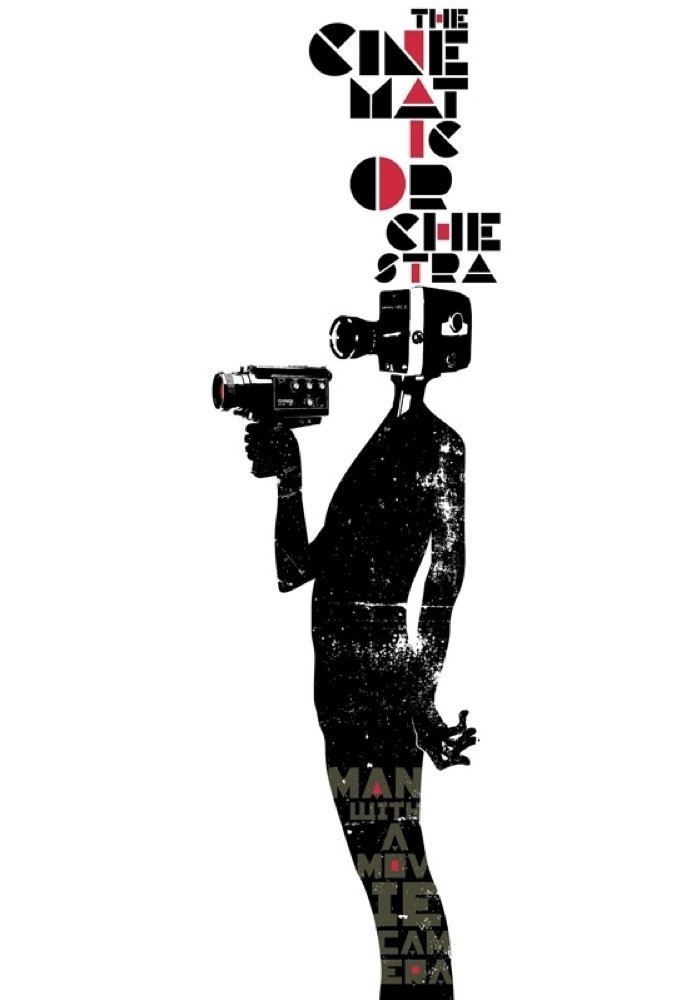

The version available in the U.S. is from Kino, and features a score by composer Michael Nyman (“The Piano“). It was premiered performed by the Michael Nyman Band on May 17, 2002 at London’s Royal Festival Hall. As the tempo mounts, it takes on a relentless momentum. Another score was created by the Cinematic Orchestra, and you can hear it while viewing nine minutes of the film here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vvTF6B5XKxQ

A famous score was created by the Alloy Orchestra of Cambridge, Mass., which devotes itself to accompanying silent cinema. To mark the 80th anniversary of the film, the Alloy obtained and restored a print from the Moscow Film Archive, and performed their revised score in the city. They will tour with the print in 2010, and on their schedule is Ebertfest 2010.

The surrealist milestone “Un Chien Andalou” (1928), by Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali, is also in my Great Movies Collection.