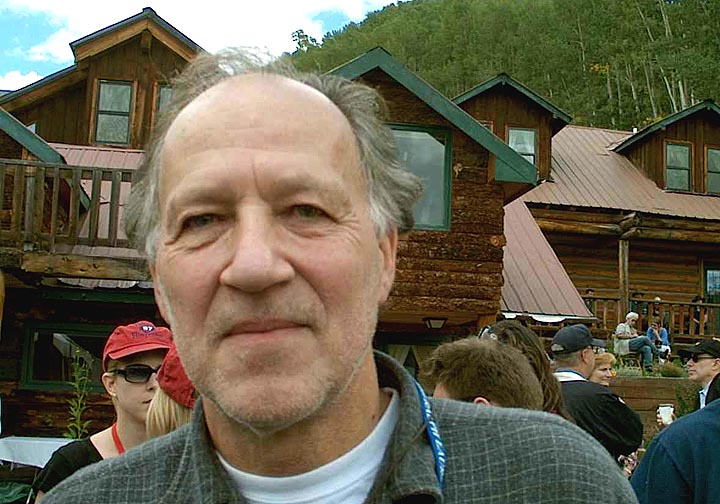

This is a lightly-edited transcript of an onstage conversation between Werner Herzog and Roger Ebert after the April 2004 screening of Herzog’s “Invincible” at Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The film involves the story of a Jewish strong man hired to appear as an Aryan god in a vaudeville theater in Germany, at the time of the rise of the Nazi Party.

Roger Ebert: You know, Werner, some months after I saw this film my wife and I were at the Pritikin Center in Florida, and we made friends with an older couple. We were talking about good films we’d seen and I told him about “Invincible” and I said, “I think the story is true” and he said, “I know it’s true because I saw him myself when I was a boy”

Werner Herzog: Yes, apparently there was a film once of the real strong-man, but only very small fragments seem to remain. I saw something like 30 seconds, which didn’t look very interesting at all. The posters are fascinating; the photos are interesting and of course the story was a bit modified. The authentic story actually ends in 1926; Zishe Breitbart died from a rusty nail that he broke through a plank just to show how strong he was. I set the story closer to Hitler’s seizing power.

RE: What I admire above all about your film is the ambition of your imagination. You do not make small films and you do not have small ideas. You told me once that our time is starving for lack of images: All the images have been worn out by television and the movies and so we have nothing more to feed our vision. And you come up with images in your film that are so remarkable, including these countless red crabs in this one, that are so frightening to me — because they are life, yet they are mindless and they just keep going on and on despite whatever we think or whatever we hope.

WH: I like the crabs a lot. Actually what you see in the film was shot on Christmas Island, actually two Christmas Islands, one in the Pacific and one in the Indian Ocean west of the Australian mainland. I spent some 10 or 12 days just waiting for the crabs to arrive because there’s only a very short window of opportunity during the very first days; 70 or 80 million crabs start migrating from the jungle to the beaches. They mate, lay their eggs and disappear back into the jungle. So it took quite an effort and some time to get them on film.

RE: But what I am amazed by is that no other director making this story, set in Europe, would feel that he had to go to the Indian Ocean to photograph crabs for it. I love the fact that your mind encompasses the …

WH: I think about them and I don’t know why. I can’t explain it. I know there’s something very big for example, to see the crabs crossing the railroad tracks, something that I can’t explain, but I know there’s something big, like for example the dancing chicken at the end of “Stroszek.”

RE: Which is one of my favorites.

WH: It is also one of my great favorites, and that image also fell into my lap. I don’t know how and why; the strange thing is that with both the crabs and the dancing chicken at the end of “Stroszek,” the crew couldn’t take it, they hated it, they were a loyal group and in case of “Stroszek” they hated it so badly that I had to operate the camera myself because the cinematographer who was very good and dedicated, hated it so much that he didn’t want to shoot it. He said, “I’ve never seen anything as dumb as that.” And I tried to say, “You know there’s something so big about it.” But they couldn’t see it.

RE: I have this series of Great Movies reviews that I’ve been writing; “Aguirre” was the first of your movies I wrote about and then I wrote about “Stroszek.” I’m going to try to quote – I believe there was a firemen or a police officer who gets on his radio…

WH: Yeah.

RE: And he calls for help and he says, “We have a dead man on a…”

WH: “We have a dead man on the ski lift, and we have a dancing chicken! Send us an electrician!”

RE: “Send us an electrician.” That film was shot in Wisconsin.

WH: Yes, and the dancing chicken was shot in Cherokee, North Carolina. When you are speaking about these images, there’s something bigger about them, and I keep saying that we do have to develop an adequate language for our state of civilization, and we do have to create adequate pictures — images for our civilization. If we do not do that, we die out like dinosaurs, so it’s of a different magnitude, trying to do something against the wasteland of images that surround us, on television, magazines, post cards, posters in travel agencies…

RE: I see so many movies that are all the same, they’re cut off like sausages, you get another two hours worth and then you go home and you forget about them. Your films expand me, they exhilarate me, they make me feel that you are trying to put your arms around enormous ideas. And at the same time there’s a feeling of hopelessness. I think of Aguirre on the sinking raft, in the middle of the river, mad, surrounded by gibbering monkeys. And Fitzcarraldo, who wanted to pull the ship across the mountain into the other river. Only you would have thought that it would have to be done with a real ship. It couldn’t be models or special effects.

WH: It was disgusting actually because at that time 20th Century Fox was interested to produce a film and we had a very brief conversation of about five sentences because it was clear their position was, “You have to do it with a miniature boat.” From there on it was clear no one in the industry would ever support something like that. It was really risky, and I knew, at that moment, I was alone with it. I tried to explain that I wanted to have the audience know that at the most fundamental level it was real. Today when you see mainstream movies, in many moments, even when it’s not really necessary, there special effects. It’s a young audience, and at six and seven kids can identify them, they know it was a digital effect, and normally they even know how they were done. But I had the feeling I wanted to put the audience back in the position where they could trust their eyes …

RE: It’s totally clear in that film that it’s a real ship and that the ropes are straining. If you look at “Lord of the Rings” for example, they have people in a chain stretched across mountainsides, and they’re obviously special effects. But in “Cobra Verde,” your film in Africa, you had a message that was being passed down a line of people for miles and miles, and it was really happening. The people were there in an endless chain on the hillsides. It’s clear that it’s really happening, and it’s extraordinary.

WH: There is a certain quality that you sense when you move a ship over a mountain. It was 360 tons and I knew I would manage it. But I knew that it would create unsightly things that no one would expect. There were many huge steel cables that are five centimeters in diameter, I mean as thick as this table. They would break like a thin thread. When you tap them before they break, when you touch them and tap them, they sound thick, they sound different, and when they break, there’s so much tension, there’s so much pressure, that the cable is red hot inside, it’s glowing inside. That was one thing I didn’t show in the film but I’ve seen it and many of you things that you see in “Fitzcarraldo” were created by the events themselves. I’ve always been after the deeper truth, the ecstatic truth, and I will always defend that, as long as there’s breath in me.

RE: And you also argue for the real locations. It would have been possible to shoot “Fitzcarraldo” without going 900 miles up the Amazon and living with arrows coming out of the jungle that could kill your crew. But you told me once of the voodoo of location; you said you also wanted to use the same locations that Murnau used for “Nosferatu” because of the vibrations…

WH: Yes, I said that, but I don’t really believe in vibrations; that belongs to the hippie age. There is one shot where a line of buildings is still standing in a city in Northern Germany which I used in much of the film, and since I knew there were a few buildings hidden in the film, I just tried to bow my head in reverence. But otherwise, sure, I’m good with locations. I know how to do it. It is not just buildings; I direct landscapes.

RE: Would you say that Murnau was your true predecessor?

WH: Yes. I believe he certainly was because I’m still convinced that there’s no better German film than “Nosferatu,” his silent film, and since we were the first postwar generation and we had no fathers, we had no mentors, we had no teachers, we had no masters, we were a generation of orphans. Many of us actually were orphans. Same thing with me but in many other cases a father just died in captivity, in the war, whatever. And those who make movies, the majority, the vast majority, died with the Nazi regime. A few were sent to concentration camps and the best left the country like Murnau and others, so the only kind of reference in my case was the generation of the grandfathers, the silent era of expressionist films. [The film critic and historian] Lotte Eisner was a great mentor of mine, who knew the entire film history, I mean she knew every single person that had worked in cinema and had an important part. She knew the brothers Lumiere, she knew Melies, who made films between 1904 and 1914, and she knew Eisenstein and all the younger ones. The young friends, the young German ones. So she was one of the very last people on this planet who had known all of them and seen all of their films, and there was not one who did not bow his or her head in reverence to her.

RE: The story that I love is that when you finished your first film, you put it in a knapsack on your back and you walked from Germany to Paris to give it to Lotte Eisner.

WH: No, that is not…

RE: Didn’t you really do that?

WH: Actually, with “Signs of Life,” my first film, I sent it by mail and she actually saw it and she sent it to Fritz Lang, saying “Finally they have cinema again in Germany.” He liked the film but the story of the walk to Lotte is kind of different. I got a call a couple of years later, a friend calls me and the phone wakes me up early in the morning. And she says, “Come quickly, come quickly, do you sit? Do you sit?” And I just said, “Yes, I’m sitting.” “Come quickly, Lotte is dying, she had a massive stroke and she is dying. Come quickly, you must come.” So I put the phone down, and I thought for a moment. I said, “I am not going to fly, I refuse to take a plane, refuse to take a car, I refuse to do anything else, I will come on foot,” because I didn’t want her to die. And I was absolutely convinced — I am not superstitious — I was totally absolutely convinced that while I was walking from Germany to Paris to see her, she would not have a chance to die, I wouldn’t allow her to die, I didn’t want her to die, it was too early. She was still needed too badly. So that was beginning of winter, that year was really bitter because we had violent storms, snow storms, rainstorms coming from the west. I took a compass reading and I took the straightest line that I could across fields, across rivers, and I arrived at Paris and she was out of hospital. She was out of hospital and survived. Eight years later, she must have been 90 years, nobody knows exactly how old she was because she started to cheat from 75 on, I think she celebrated her 75th birthday a couple of times. And very casually, we were having tea, and she said to me, nibbling on a cookie, she said to me, “Listen, listen to me, I’m almost blind, I cannot read any more, I cannot see any more films, I cannot walk any more, I’m tired of life” — she actually even said it “sucked” and she was saturated of life, and she said to me, “but there’s still this spell on me, that I must not die” and I said to her very casually “The spell is lifted” and two weeks later she died. And she died at the right time then, it was good, it was good to die then. So I didn’t carry a print on my back.

RE: It is a wonderful story.

WH: Actually I do like to carry prints, because it somehow verifies a strange fact which is hard for me to believe. Very often I think I might just be dreaming; could it be my brother who made the film, and I tried to claim that it was me? I don’t really know. I had a strange father who didn’t impact at all in my life. When I met him once in a while, he was living a completely invented sort of life. He spoke about some sort of universal scientific study that he had written but I knew he had never written one line. And he kept on studying and studying in I don’t know how many fields, and he would talk to visitors, even his own boys, to his own children, he would talk about his study, even though we would know he had never written it. And I remember one moment I touched his shoulder and said, “Yes, but you’ve never written it.” And he looked at me and somehow realized in a moment he hadn’t written it, but five minutes later he was raving about it again. So very often I think “Yeah, have I really made films or not?” And I carry a print once in a while; you feel the weight of it, weight like fifty pounds.

RE: You have made the film.

WH: (laughs) Yeah.

RE: This film “Invincible” begins with the little boy and his relationship with his brother, and him telling the story about the rooster. And that fable sets the stage for the film because this films plays to me like a fable, like one of those stories about giants and strong men and about how they come to the city and how they save the maiden and vanquish the villain. Its simplicity is so beautiful. The hero has a misplaced trust in strength, muscles are not going to be the answer, but his mind, his purity, is so clear about that. The story affects me on a level of fable and allegory.

WH: Yes, I liked the rooster story a lot and I knew it had to be in the film. It’s good to open the film like that. And of course what makes a lot of difference in stories like this is, he’s in love with the young pianist, but there’s an equal love story with his younger brother. In something like, I don’t know exactly, like 50 films, I’ve never filmed a kiss. And in this film all of a sudden it’s a very tender, very fleeting kiss. I’ve never done a kiss in my life in a movie. Nor telephone calls, do they occur in my movies. People driving in cars do not affect me much; very few times do you see people driving. In a few of my films you see some cars. It probably reflects the fact that I grew up in a very remote place, the most remote place in the Alps mountains, and until I was 11 I had not seen films, I actually did not even know of the existence of movies. And we would run when we saw a motorcar. Like in the film, we would really run when a motorcar was passing, we wanted to look. I made my first phone call at the age of 17.

RE: I don’t want to prompt you with another story that I probably have wrong, but when you mention being 11, I’m trying to remember the details of something you told me once of having seen Klaus Kinski. When you were young.

WH: I was 13 then.

RE: Thirteen. And knowing, somehow. You saw him and you knew something.

WH: We had moved to Munich, and we lived in some sort of a boarding house, the four of us, my mother and my two brothers, so it was four persons in one room. One day, the owner of the place, an elderly lady who had a heart for starving artists, picked up Kinski literally from the street, well, actually from an attic that he had occupied, he had squatted in an attic and filled it up with autumn leaves, and made huge scandals, and would climb up to the roof and defy policemen who would try to arrest him. And she picked him up and fed him and gave him a very small room in our boarding house. She did his laundry, fed him, everything, for free. And from the very first moment I was terrorized. Everyone was in sheer terror. It took him only 48 hours and the entire bathroom was in smithereens.

He would yell and scream, and the only one that was not afraid — who was just in amazement and wonderment — was a young peasant women, something like 17 or 18 years old. She was not afraid at all and she had a tray and Kinski flung the tray against the wall and all the dishes left a mess and I still see her, she bends down, slowly picks up the empty tray, and smacks him in the face with it. And he would calm down for a moment, but it was only fleeting, because he would be like, how should I say, like a hurricane. Laying waste two apartments, movies, he would wreck cars, he would wreck Ferraris, no it was not Ferraris, it was Rolls-Royces, at a rate of a Rolls Royce a week.

Later when he was in Italy and earned a lot of money, there was always a trail of devastation behind him, and some of it was not funny because part of him was really, really, really bad. So he may rest in peace and make his peace with the creator if ever he encounters him. So then I was 13. And of course one day I asked him to do “Aguirre.” When I sent him the screenplay, 12 years later, I knew if he would accept it, what I had to expect, but I was never afraid.

RE: Many directors do not hire someone that they believe is going to be trouble.

WH: No, it was much more.

RE: It was much more than trouble. You were going take him into the middle of the rain forest hundreds of miles from anything and live with him there for months. And it was a film that you could not possibly start again if anything went wrong. And you bet everything on that. When we think of “Aguirre” we think of Kinsey, so yours was the right decision, but what a chance you took.

WH: When you know that there is only one option that you have, there is no alternative. There is absolutely no alternative. But Kinsey doing Aguirre must not be afraid of actually doing it, and no matter what comes along you will prevail as long as it’s a secure vision.

RE: The legend is that Kinski accepted movies entirely on the basis of convenience and location.

WH: Money.

RE: Money.

WH: He would even do hard-core pornos for money. Money, money, money! And if for any reason he would start to scream, he would scream until he had frost on his mouth. He would scream about this pig who didn’t offer him decent money, who was this psychopathic asshole. Obviously he made some distinctions, because I obviously paid him much less than others would offer him. I mean a fraction of that. I didn’t have the budget. Kinski the bastard won a third of the entire budget.

And then, there’s an interesting thing, the real good version is the German version, it’s the authentic version, but since we filmed a lot in rapids there was such a huge noise that — of course we did have some direct sound — but you could hardly understand a word. We had to post-synch it, so I said to Klaus, “We need you for looping, for one and a half days.” He said, “Yes, I’m coming, but it will cost a million dollars.” And there was absolutely no way. He knew, of course, I didn’t have a thousand dollars, everything was gone, my wrist watch was gone, everything, and he asked for a million dollars, he hated the film so badly you could not believe it. And he didn’t show up for looping so I looped it with a different voice, and the voice is as good as Kinski. I took a lot of effort; nobody, nobody would ever know. But you know it now. Can you please not… do not leak to the press.

RE: But you have just told 1,600 people. (Laughter) What is astonishing, you returned to the jungle for “Fitzcarraldo,” and it seemed like you both wanted to do this.

WH: We were not mad I think. He understood that there was a higher duty that both of us had to accept. That was actually the most dangerous of all, because of course I could tolerate all sorts of things, and it was not only Kinski that was hard to take. Moving the ship over the hill was something you could not imagine, and we had all sorts of catastrophes. We had two plane crashes. We had people shot with huge arrows at the throat that almost killed them and we operated on them on kitchen tables. Everything in the book happened, with now Kinski on this location. Everyone in the crew after two days would turn against me: “How can you have the guts to bring in this pestilence again? We are refusing!” The actors on a daily basis would threaten to terminate with a strike. For me there was one borderline, it was duty, a high duty. High duty on which he stood and I stood.

In “Aguirre,” at the end, ten days before the end of shooting, Kinski, I believe as usual, didn’t learn his lines. They were very short lines anyway, and he all of a sudden interrupts everything and throws everything around and he screams in a tantrum and destroys half the set and screams that the still photographer had smiled and had to be dismissed on the spot. Of course I wouldn’t dismiss him because everyone else would have walked out in solidarity.

I said “No, I’m not doing it, let’s calm down and we’ll continue.” And he left the set. And I knew why he had done it because he had done it 35 times just within the last five years. And because of that, movies were canceled and destroyed. It was too well documented. He packed his things into a speedboat and screamed and screamed. And it was somehow not correctly reported in the press, but I have witnesses that I was unarmed, and did not point a gun at him, but I walked up and I said to him, “Klaus, I don’t have to make up my mind. I’ve had months of deliberating where is the borderline that we will not transgress. This would be the transgression, the borderline. This is something that you will not survive.”

I said to him, “I do have a rifle,” very calmly. He could try to take the boat and he might reach the next bend of the river but he would have eight bullets through his head. But of course there were nine bullets, and I said, “Guess who gets the last one?” And he looked at me and he understood it was not a joke anymore. I would have done it. He understood he better behave, and it was kind of hostile for the next couple of days. But what I’m trying to say is, the incident may sound funny now, and it seems funny and bizarre to me; if I sat out there I would laugh with you. But what I’m trying to say is that there’s always been a very clear borderline, a line that must not be stepped over. So once you accept the duty you have to understand the duty that is upon you. I’ve always understood it myself.

RE: In “Invincible” you have the opposite kind of actor; I think your star [Jouko Ahola] was actually from Scandinavia.

WH: Twice he was named the strongest man in the world.

RE: He seems like the sweetest man alive, and his smile is so warm.

WH: He is the opposite of Kinski; he’s a very sweet man. And you could tell instantly, the first moment that you would see the man, you have that feeling in a particular woman’s sense, you sense the confidence and weakness of the man, from five miles away. No it’s true, they love him. And he somehow had a way with for example with Anna Gourari, who plays the pianist in Tim Roth’s show.

The strong man was reluctant to accept the role, because he’d never been in a movie and he said, “Well, can I do that?” and I said, “Yes, you can do it. I know my job and I know how to make you into a convincing actor; you just have to have the confidence in your physical strength and you have to have the confidence in who you are. And you should trust your own eyes, so if you lift 900 pounds off the ground, you believe it is actually 900 pounds.”

He showed up and he can lift more, so-called dead lifting. He bowed down and lifted it up off the ground on to his knees and he held it up in Los Angeles, where all the muscle men are working out, including Schwarzenegger, a hundred of them. He brought his own bar because he needs an elongated bar to put on weight after weight after weight. And he does that, he starts pumping iron and they surround him and then he has nearly 400 men around him and just staring at the 1000 pounds. He crouches down. Lifts it, drops it, walks away and takes a shower.

RE: And at the opposite end of the physical scale, Tim Roth, the ninety pound weakling, one of the best actors in the world.

WH: Yes he is, yes he is.

RE: The sensation I’ve had each time I see the film is that if I wanted to, if I didn’t actually didn’t decide not to, I would be hypnotized by him. He’s looking directly at me through the screen.

WH: That’s actually happened, I taught him how to hypnotize, because I did once an entire feature film that…

RE: “Heart of Glass!”

WH: “Heart of Glass,” yes, I did that film with the entire cast under hypnosis. And so I taught Tim Roth how to do it and the funny thing was that the cinematographer was looking through the eyepiece and sitting that close and all of a sudden started to weave, and I grabbed him by the hair while the scene was still running and softly shook him. So yes, if the audience will be willing, it can be hypnotized from the screen. And that was what I actually had planned to do in “Heart of Glass”; I actually had the idea that I would appear on screen myself, and explain that I was the director and the scenes were shot under hypnosis. “And if you are willing to see the film under hypnosis, you should follow my advice now. I will ask you to look at something like a pencil, and don’t remove your eyes, and listen to my voice and follow my words and follow my instructions.”

And of course I would tell the audience that at the end of the film they will return to the screen and softly wake up again. I have actually shown films to audiences who were hypnotized, including for example “Aguirre.” With “Aguirre” it was very strange because I remember that one young women who saw the film was constantly circling around “Aguirre” as if she was a helicopter and she could see behind.

RE: “Heart of Glass” is a great film about a community that looses the secret of making rose-tinted glass.

WH: Ruby Glass.

RE: Ruby glass that has sustained this community for many generations. The shot that I always remember is the two guys looking at each other from across the table and drinking beer and one reaches up and breaks his bear stein over the other one’s head. And the other one make no reaction.

WH: Yeah, but I’ve seen things like that when I grew up in the country, and I could predict that in 10 minutes there would be a fight. And they would be all quiet and just stare at each other. I would know the ritual of how they would finally take up the steins and break them over each other’s heads. Actually in Bavaria there’s a law that there must be two grooves on either side of a stein so that it breaks easier when you hit, because it can fracture your skull.

RE: It is impossible to ask you anything without being fascinated by the answer. It’s 2 a.m. and no one has left; you’ve got them hypnotized.

WH: It’s gotten very late.