Who else but Werner Herzog would make a film about a retarded ex-prisoner, a little old man and a prostitute, who leave Germany to begin a new life in a house trailer in Wisconsin? Who else would shoot the film in the hometown of Ed Gein, the murderer who inspired “Psycho” (1960)? Who else would cast all the local roles with locals? Who else would end the movie with a policeman radioing, “We’ve got a truck on fire, can’t find the switch to turn the ski lift off, and can’t stop the dancing chicken. Send an electrician.”

“Stroszek” (1977) is one of the oddest films ever made. It is impossible for the audience to anticipate a single shot or development. We watch with a kind of fascination, because Herzog cuts loose from narrative and follows his characters through the relentless logic of their adventure. Then there is the haunting impact of the performance by Bruno S., who is at every moment playing himself.

The personal history of Bruno S. forms the psychic background for the film. Bruno was the son of a prostitute, beaten so badly he was deaf for a time. He was in a mental institution from the ages of 3 to 26–and yet was not, in Herzog’s opinion, mentally ill; it was more that the blows and indifference of life had shaped him into a man of intense concentration, tunnel vision, and narrow social skills. He looks as if he has long been expecting the worst to happen.

Herzog, who with Wim Wenders and Rainer Werner Fassbinder brought forth the New German Cinema in the late 1960s and 1970s, saw Bruno in a documentary about street musicians. He cast him in the extraordinary film “Every Man for Himself and God Against All” (1974), also known as “The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser.” It told the story of an 18th century man locked in a cellar until he was an adult, and then set loose on the streets to make what sense he could of the world. Bruno was uncannily right for the role, and right, too, for “Stroszek,” which Herzog wrote in four days.

Ah, but there is a reason why the screenplay came quickly. Herzog had the location already in mind. He and the American documentarian Errol Morris had become fascinated by the story of Ed Gein, who dug up all of the corpses in a circle around his mother’s grave. Did he also dig up his mother? They decided they had to open the grave to see for themselves. In Q&As we had during tributes at Facets in Chicago and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Herzog told me the story: Morris did not turn up as scheduled in Plainfield, Wis., the grave was never opened, but Herzog’s car broke down there and he met the mechanic whose shop provides a key location and character for the film.

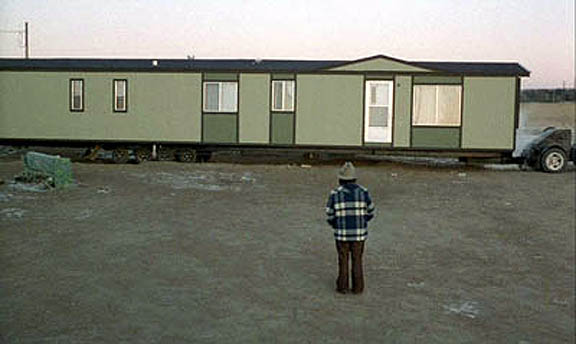

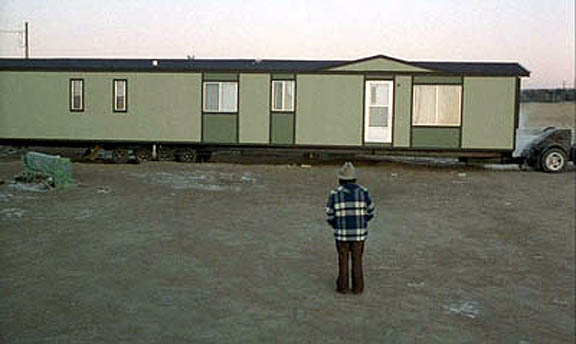

With the destination in mind, Herzog found the story writing itself. The film opens with Bruno (Bruno S.) being released from prison, walking into a bar, and meeting Eva (Eva Mattes), a prostitute whose pimp mistreats her. He offers her refuge in his apartment, which has been looked after by the elderly, tiny Mr. Scheitz (Clemens Scheitz). Mr. Scheitz announces that his nephew in Railroad Flats, Wis., has invited him to move there. It is time, Bruno announces, for them all to begin their new lives. Eva raises money through prostitution (her clients are Turkish workers at a construction site), and the three find themselves in Wisconsin and in possession of a magnificent new 40-foot 1973 Fleetwood mobile home.

But this plot summary sounds mundane, and the tone of the movie is so strange. “Stroszek” is not a comedy, but I don’t know how to describe it. Perhaps as a peculiarity. We get the sense that Herzog is adding detail on the spot: as Railroad Flats happens to the characters, it happens to the film. Mr. Scheitz’s nephew is played by Clayton Szalpinski, the very mechanic who repaired Herzog’s car, and he regales the newcomers with local color. A farmer and his enormous tractor have gone missing, and Clayton believes they are to be found at the bottom of one of the many local lakes. He has a metal detector, and on days when the ice is thick enough, he searches.

Bruno is sure the idyll cannot last. He is positive that the papers they signed at the bank will sooner or later require them to make payments, and he is right. Scott McKain plays a painfully polite bank employee who tries to explain that the TV set “might/would” have to be repossessed (he often uses two words to take the edge off of both; McKain perfectly captures the tone of a man embarrassed to be bringing up money). Eventually there is the unforgettable sight of the Fleetwood being towed off the land, leaving Bruno to stare at the forbidding winter Wisconsin landscape. He knew something like this would happen.

The thing about most American movies is that the actors in them look like the kinds of people who might be hired for a movie. They don’t have to be handsome, but they have to be presentable–to fall within a certain range. If they are too strange, how can they find steady work? Herzog often frees himself of this restraint by using non-actors. Clayton Szalpinski, for example, has an overbite and backwoods speech patterns, but he is right for his role, and no professional actor could play a small-town garage mechanic any better. And Bruno S. is a phenomenon. Herzog says that sometimes, to get in the mood for a scene, Bruno would scream for an hour or two. In his acting he always seems to be totally present: There is nothing held back, no part of his mind elsewhere. He projects a kind of sincerity that is almost disturbing, and you realize that there is no corner anywhere within Bruno for a lie to take hold.

Many movies end with hopeless characters turning to crime. No movie ends like “Stroszek.” Bruno and Mr. Scheitz take a rifle and go to rob the bank, which is closed, so they rob the barber shop next door of $32 and, leaving their car running, walk directly across the street to a supermarket, where Bruno has time to pick up a frozen turkey before the cops arrest Mr. Scheitz. Bruno then drives to a nearby amusement arcade, where he feeds in quarters to make chickens dance and play the piano. Then he boards a ski lift to go around and around and around.

This last sequence is just about the best he has ever filmed, Herzog says on the commentary track of the DVD. His crew members hated the dancing chicken so much they refused to participate, and he shot the footage himself. The chicken is a “great metaphor,” he says–for what, he’s not sure. My theory: A force we cannot comprehend puts some money in the slot, and we dance until the money runs out.

“Stroszek” has been reviewed as an attack on American society, but actually German society comes out looking worse, and all of the Americans seem naive, simple and nice, even the bank official. The film’s tragedy unfolds because these three people have nothing in common and no reason to think they can live together in Wisconsin or anywhere else. For a time Eva sleeps with Bruno, but then she closes her door to him, and in a remarkable scene he shows her a twisted sculpture and says, using the third person, “this is a schematic model of how it looks inside Bruno. They’re closing all the doors on him.”

Earlier in the film, in Berlin, after he loses his job and his girl, Bruno goes to a doctor for help. This man (Vaclav Vojta) listens carefully, is sympathetic, has no answers, and takes Bruno into a ward where premature babies are being tended. Look, he says, how tenacious the grip reflex is, even in this little infant. A child clings to the doctor’s big fingers. Bruno looks. We can never tell from his face what he is thinking. The baby cries, and the doctor tenderly cradles it, kissing its ear, and it goes to sleep. That is, perhaps, what Bruno needs.

“Stroszek” and several other Herzog films have been newly restored and released by Anchor Bay on DVD, with a commentary track by the director. Included: “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” (which is also the subject of a Great Movie essay), “Heart of Glass,” “The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser,” “Woyzeck,” “Fitzcarraldo” “Nosferatu,” and “My Best Fiend.”