The artist Ralph Steadman is a rather unprepossessing looking man; with a slightly stocky build and generous shocks of white hair about his temples, he resembles an arguably typical British man of a certain age. (In point of fact, his ruddy complexion and mostly amused but also sincere sense of self-possession make him seem a good deal younger than his 77 years.) These are all nice ways of saying he’s not exactly what immediately comes to mind when contemplating a dynamic onscreen presence.

But the work of Ralph Steadman—the art that he creates with splatters of India Ink among the other sometimes more arcane ingredients he keeps in his arsenal of aesthetic alchemy—that is stuff of great visual interest indeed. The hundreds of drawings, paintings, sketches, all almost savagely expressive, bursting with Swiftian indignation, hallucinatory imagery, and humor both dazzlingly sophisticated and scatology-obsessed-schoolboy crude, that’s all stuff for the eyes to revel in, and the signal virtue of “For No Good Reason,” a documentary about Steadman, is that it puts a lot of that work up on the big screen to galvanic effect.

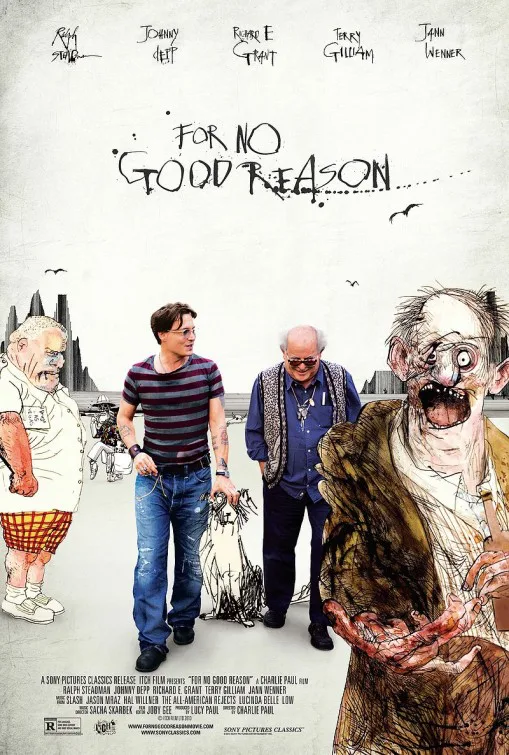

The signal defect of “For No Good Reason,” on the other hand, is that first-time director Charlie Paul appears to not know how good he has it merely in his ability to do that very thing. “For No Good Reason” gives a good beginner’s overview of Steadman, and both why he is important and why he is great, but it also doesn’t trust itself, or perhaps the audience it’s trying to reach, enough to not get too cutesy too often. The movie’s approach teems with visual trickery—making animated mini-films out of some of Steadman’s most famous drawings, an effect that is only worthwhile maybe a third of the times it’s tried—a lot of gratuitous background music by Famous Rock Persons, and its big-name interviews are presented in a rather arty and distracting way. Not that the big-name interviews are themselves gratuitous. “Rolling Stone” publisher and editor Jann Wenner provides, in a banal way that’s almost welcome, some context concerning Steadman’s famous collaboration with the gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, while record producer Hal Wilner recounts a Steadman teaming with William S. Burroughs with droll irony.

The movie itself is practically hosted by Johnny Depp, who of course incarnated Thompson in “Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas,” the amazing film adaptation of the Thompson book directed by Terry Gilliam (who also has a few words to say in this movie). He shows up at Steadman’s home and watches in (entirely justified) awe as Steadman improvises a few drawings for him, revealing a battery of technique that I reckon is practically unique in contemporary art. I infer that Depp’s onscreen participation is pretty important to this movie’s existence, and also not insignificant relative to the fact that it’s being distributed by Sony Pictures Classics. On the one hand, I say whatever works. On the other hand, there are several instances herein in which Depp’s presence feels, well, obtrusive.

That said, I learned more about Steadman than I had known, and was glad to do so. The documentary does keep a commendable eye on the work (you’d never figure out from “For No Good Reason” that he’s been married for over 40 years to the same woman, for instance), but I wish that it had done so without putting it into such a particularly gilded frame.