Hunter S. Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” is a funny book by a gifted writer, who seems gifted and funny no longer. He coined the term “gonzo journalism” to describe his guerrilla approach to reporting, which consisted of getting stoned out of his mind, hurling himself at a story, and recording it in frenzied hyperbole.

Thompson’s early book on the Hells Angels described motorcyclists who liked to ride as close to the line as they could without losing control. At some point after writing that book, and books on Vegas and the 1972 presidential campaign, Thompson apparently crossed his own personal line. His work became increasingly incoherent and meandering, and reports from his refuge in Woody Creek, Colorado depicted a man lost in the gloom of his pleasures.

Ah, but he was funny before he flamed out. “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” is a film based on the book of the same name, a stream-of-altered-consciousness report of his trip to Vegas with his allegedly Samoan attorney. In the trunk of their car they carried an inventory of grass, mescaline, acid, cocaine, uppers, booze, and ether. That ether, it’s a wicked high. Hurtling through the desert in a gas-guzzling convertible, they hallucinated attacks by giant bats, and “speaking as your attorney,” the lawyer advised him on drug ingestion.

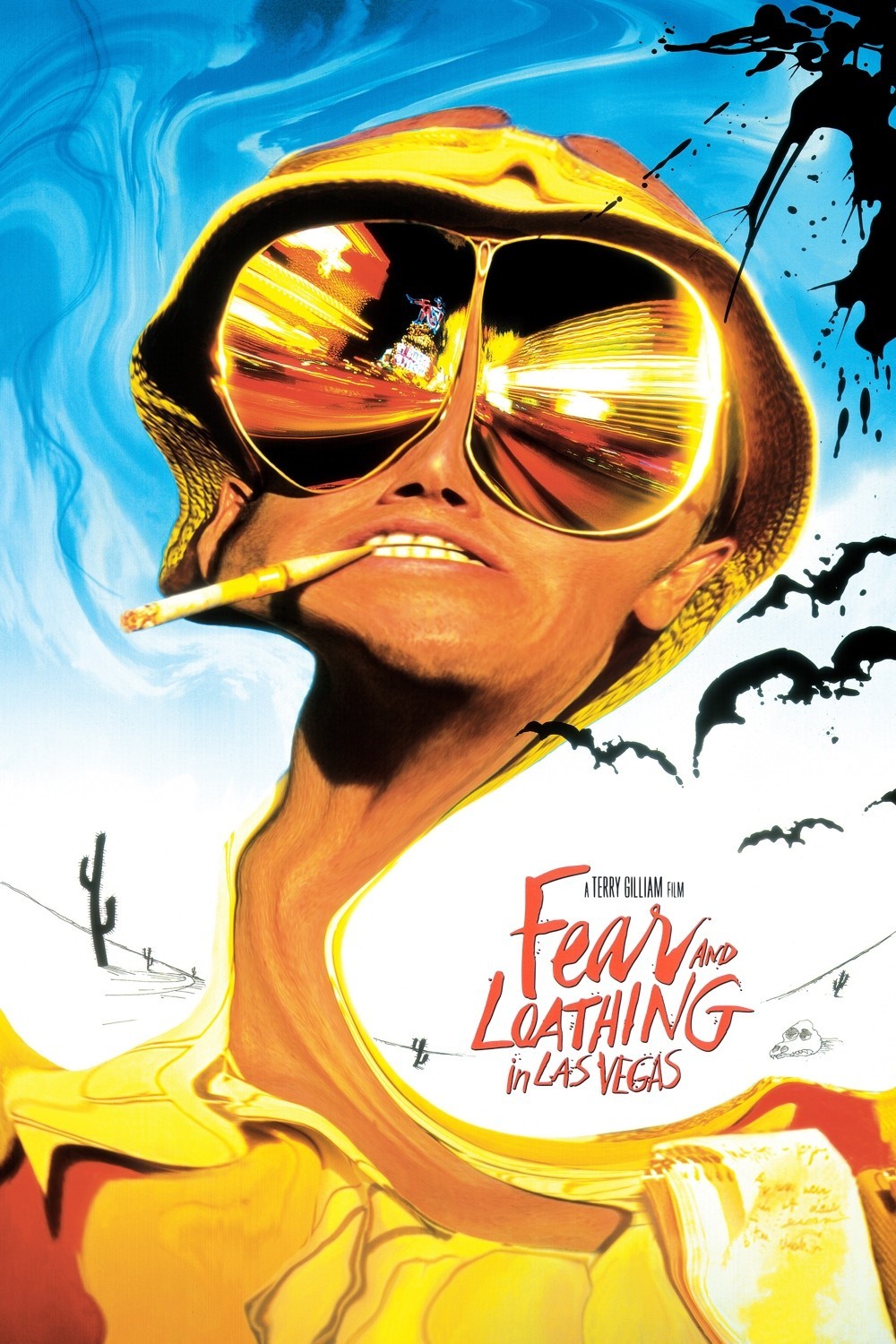

The relationship of Thompson and his attorney was the basis of “Where the Buffalo Roam,” an unsuccessful 1980 movie starring Bill Murray as the writer and Peter Boyle as his attorney. Now comes “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” with Johnny Depp and Benicio Del Toro. The hero here is named Duke, which was his name in the original Thompson book and is also the name of the Thompson clone in the Doonesbury comic strip. The attorney is Dr. Gonzo. Both Duke and the Doctor are one-dimensional walking chemistry sets, lacking the perspective on themselves that they have in both the book and the strip.

The result is a horrible mess of a movie, without shape, trajectory or purpose–a one joke movie, if it had one joke. The two characters wander witlessly past the bizarre backdrops of Las Vegas (some real, some hallucinated, all interchangeable) while zonked out of their minds. Humor depends on attitude. Beyond a certain point, you don’t have an attitude, you simply inhabit a state. I’ve heard a lot of funny jokes about drunks and druggies, but these guys are stoned beyond comprehension, to the point where most of their dialog could be paraphrased as “eh?” The story: Thompson has been sent to Vegas to cover the Mint 400, a desert motorcycle race, and stays to report on a convention of district attorneys. Both of these events are dimly visible in the background; the foreground is occupied by Duke and Gonzo, staggering through increasingly hazy days. One of Duke’s most incisive interviews is with the maid who arrives to clean the room he’s trashed: “You must know what’s going on in this hotel! What do you think’s going on?” Johnny Depp has been a gifted and inventive actor in films like “Benny and Joon” and “Ed Wood.” Here he’s given a character with no nuances, a man whose only variable is the current degree he’s out of it. He plays Duke in disguise, behind strange hats, big shades, and the ever-present cigarette holder. The decision to (ital) always (unital) use the cigarette holder was no doubt inspired by the Duke character in the comic strip, who invariably has one–but a prop in a comic is not the same thing as a prop in the movie, and here it becomes not only an affection but a handicap: Duke isn’t easy to understand at the best of times, and talking through clenched teeth doesn’t help. That may explain the narration, in which Duke comments on events that are apparently incomprehensible to himself on screen.

The movie goes on and on, repeating the same setup and the same payoff: Duke and Gonzo take drugs, stagger into new situations, blunder, fall about, wreak havoc, and retreat to their hotel suite. The movie itself has an alcoholic and addict mind-set, in which there is no ability to step outside the need to use and the attempt to function. If you encountered characters like this on an elevator, you’d push a button and get off at the next floor. Here the elevator is trapped between floors for 128 minutes.

The movie’s original director was Alex Cox, whose brilliant “Sid and Nancy” showed insight into the world of addiction. Maybe too much insight; he was replaced by Terry Gilliam (“Brazil,” “Time Bandits“), whose input is hard to gauge; this is not his proudest moment. Who was the driving force behind the project? Maybe Depp, who doesn’t look unlike the young Hunter Thompson but can’t communicate the genius beneath the madness.

Thompson may have plowed through Vegas like a madman, but he wrote about his experiences later, in a state which for him approached sobriety. You have to stand outside the chaos to see its humor, which is why people remembering the funny things they did when they were drunk are always funnier than drunks doing them.

As for Depp, what was he thinking he made this movie? He was once in trouble for trashing a New York hotel room, just like the heroes of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” What was that? Research? After River Phoenix died of an overdose outside Depp’s club, you wouldn’t think Depp would see much humor in this story–but then, of course, there *isn’t* much humor in this story.