No movie has ever been able to provide a catharsis for the Holocaust, and I suspect none will ever be able to provide one for 9/11. Such subjects overwhelm art. The artist’s usual tactic is to center on individuals whose lives are a rebuke to the tragedy. They sidestep the actual event and focus on a parallel event that ends happily, giving us a sentimental reason to find consolation. That is small comfort to the dead.

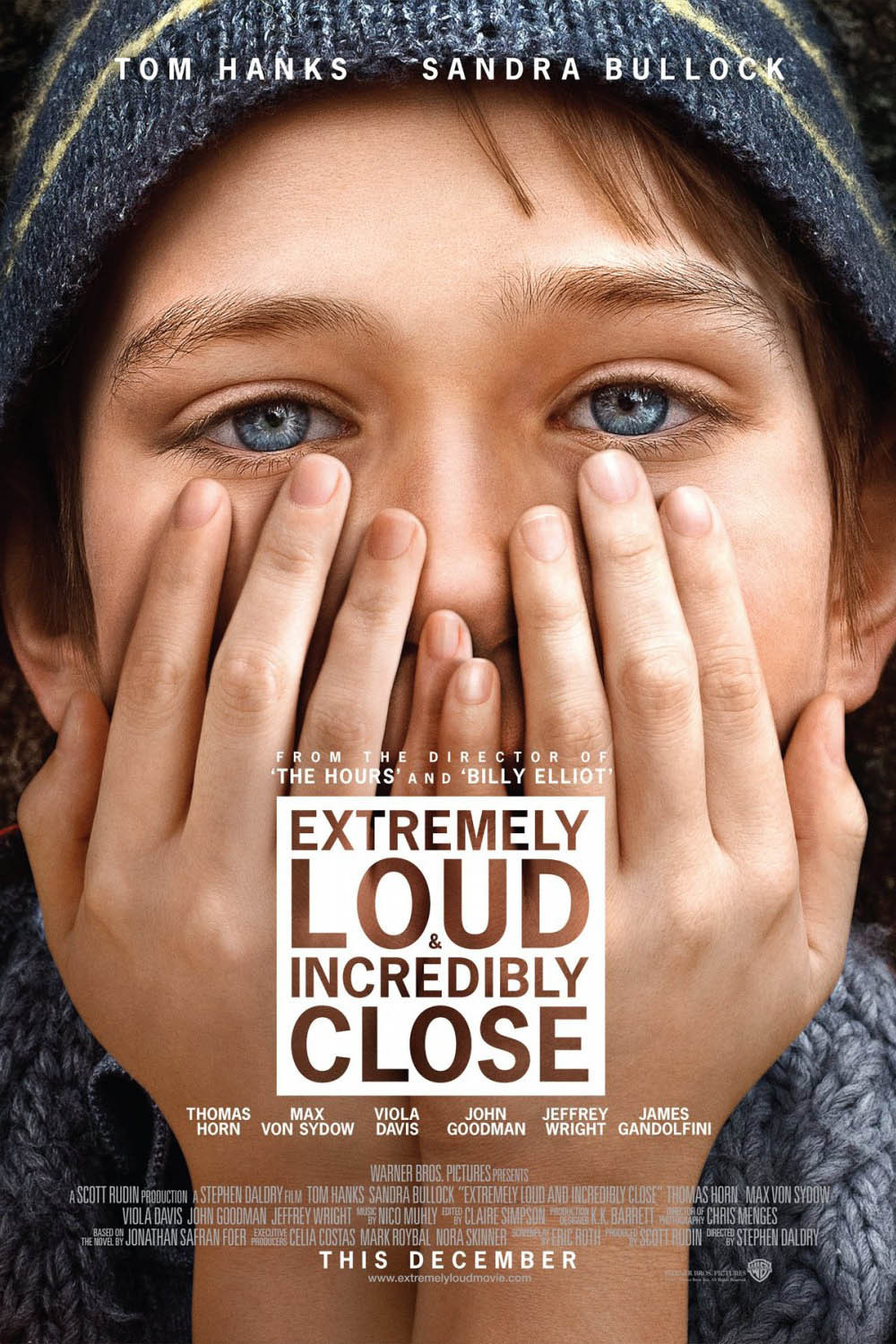

“Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close” tells the story of an 11-year-old boy named Oskar Schell, who is played by the gifted and very well cast Thomas Horn. His father was killed in 9/11. Indeed, intensely scrutinizing videos of bodies falling from one of the towers, Oskar fancies he can actually identify him. We see a lot of Thomas, his father, in flashbacks, and he is played by Tom Hanks, who has come to embody an American Everyman. As a father, Thomas was a paragon, spending countless quality hours with Oskar and involving the bright kid in ingenious mind games. Perhaps he suspected what Oskar now tells us about himself: He may have Asperger’s syndrome, a condition affecting those who are very intelligent but lack ordinary social skills. For a kid like that, driven to complete tasks he has set for himself, his dad’s challenges are compelling.

The film opens with the father’s funeral (the casket is empty). We meet Oskar’s mother, Linda (Sandra Bullock), who Thomas feels distant from and resents for being the parent who is still alive. He has no idea how much he hurts her. He is close with his grandmother (Zoe Caldwell) and learns that his paternal grandparents were Holocaust victims.

In a vase on the upper shelf of a closet, Oskar finds an envelope with the word “Black” on it. It contains a key. Oskar decides that the key might unlock a secret of his father’s past — perhaps a message. Because the word is capitalized, he decides it is a name, and he sets out to visit everyone named Black in New York City. From a city phone book, he comes up with a list of 472 of them. Oskar sets out on foot, because one of his peculiarities is that he won’t use public transportation. To boost his confidence, he takes along his tambourine. That he is able to undertake this task while apparently keeping it a secret from his mother is a tribute to his intelligence. That he thinks it’s safe for an 11-year-old to walk alone all over New York is not.

We don’t follow him on every visit, but the first one makes a big impression. He knocks on the door of Abby Black (Viola Davis), who invites him in, hears his story and tries to help him. Oskar’s social skills don’t extend to noticing that Abby is in the middle of a marital crisis with her husband (Jeffrey Wright). Davis and Wright are so good here, in roles that work mostly by implication, that Oskar’s quest starts off on the right foot emotionally.

What do we learn during this quest? That more than 4,000 may have died in the 9/11 terrorism, but millions more still live? That those named Black form a cross-section of the metropolis? That life goes on? Oskar is not entirely alone. He is seen off by his building’s doorman (John Goodman), and soon he makes a new friend. This very old man, known only as the Renter (Max von Sydow), has moved in with Oskar’s grandmother. He cannot or will not speak, communicating only with written notes, but he is a tall and reassuring companion. (Some will observe that von Sydow played chess with Death in “The Seventh Seal,” a connection that might appeal to Oskar’s analytical mind.) You will discover if the key unlocks anything, or if the search for its lock is itself the purpose.

The screenplay is by Eric Roth, whose “Forrest Gump” and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” also were about strange journeys in life. The director is Stephen Daldry, whose “The Reader” also approached the Holocaust obliquely. There may be some significance in the name Oskar, from Jonathan Safran Foer’s original novel; that was the name of the hero of Gunter Grass’ The Tin Drum, about a boy who travels around Europe during World War II and carries not a tambourine, but a drum.

You will not discover, however, why it was thought this story needed to be told. There must be a more plausible story to be told about a boy who lost his father on 9/11. This plot is contrivance and folderol. The mysterious key, the silent old man and the magical tambourine are the stuff of fairy tales, and the notion of a boy walking all over New York is so preposterous we’re constantly aware of it as a storytelling device. The events of 9/11 have left indelible scars. They cannot be healed in such a simplistic way.