“Everybody Knows… Elizabeth Murray” is an intentionally ironic title for a documentary about a contemporary artist who had to fight longer and harder for recognition than any male counterpart of similar ability in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. So it is both bitter and sweet that the year before Murray died from lung cancer at the age 66, she would become one of a few women to ever be granted their own retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

And yet she never achieved much fame beyond her devoted admirers and peers in the art world. Invariably, it was other women who gave her a boost—a high-school teacher who paid for her to attend the Chicago Institute of Arts, powerful Soho gallery owner Paula Cooper, who provided invaluable exposure. Her gender at least came in handy when she was a single mother in the ‘70s, struggling to make a living wage. That is when CalArts decided to recruit female visiting artists to its campus. As she says about that period, “The recognition is soul food. I never knew I could make money from it.”

Her work now permanently graces such hallowed museums as the Hirshhorn in Washington, D.C., and the Guggenheim. But she also proudly provided a 120-foot mosaic mural for the Lexington/ 59th Street subway stop in Manhattan—something not touched upon in the doc. Highbrow was just not her thing. Speaking to the masses as they commuted each day—that appealed to Murray.

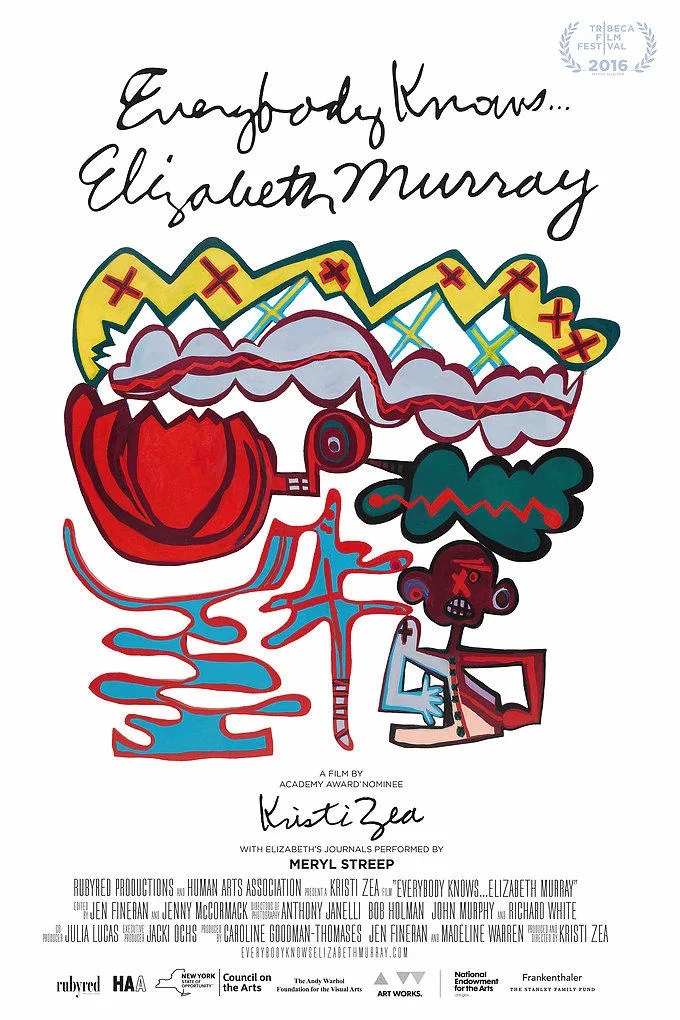

But once you see the incredible late-career billboard-size pieces that Murray left behind—unwieldly and intentionally broken canvases willed into unique, brightly hued designs that often incorporated recognizable objects such as coffee cups, shoes and even human shapes amid abstract forms—you will grasp how distinctly disarming her moody yet playful vision was with its stylistic echoes of jigsaw puzzles, graffiti, pop art and cartoons. What is even better is how these bold and bulky pieces with their splashes of color and often biomorphic shapes offer not just a uniquely feminine point of view but also a humanistic one that attempts to reflect the emotional chaos of our everyday existence.

First, we must learn how Murray got to this marvelous point of acclaim in her career just before her demise. Directed and produced by Oscar-nominated production designer Kristi Zea, a friend of Murray’s who has frequently collaborated with Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme (both of whom have made their share of acclaimed documentaries), this engaging hour-long tribute regularly serves as a microcosm of what it is like for a woman to fight for attention in a historically male-dominated field.

Murray, who had a miserable childhood and grew to crave domesticity, actually made the decision after remarrying to have two more children in her 40s, while pursuing a healthy balance between her work demands and her family obligations. Luckily, she had the forethought to be filmed while preparing for her MoMA show, despite her failing health—a topic that she is open about but does not dwell on. While the photos that are used to fill in the blanks of her earlier life reveal she has always had a slim physique, the artist in this footage looks especially gaunt, and what is left of her white hair barely covers her head. But when she speaks on camera, her large blue eyes grow animated and her broad smile confirms the healing joy that she felt during the act of creation.

Zea also makes good use of her access to Murray’s journals, which reveal her philosophy about her profession and state of mind during her earlier years. We should all be so lucky to have Meryl Streep to express our thoughts for us. The actress does her job with such finesse, you might forget it isn’t Murray talking when she makes incisive observations on such topics as why male artists resent women: “If we can give birth to real babies, then why should we be able to create art? Isn’t the real thing enough?”

An artist doesn’t just want to produce art. They want to share that gift and have it be understood. By those standards, Zea’s homage definitely is a success, especially given the way she bookends her film. We begin with Murray toiling over her final masterpiece—which just happens to be called “Everybody Knows”—and we witness her apply her finishing strokes of paint by the end. Thanks to a visit to her farm in Upstate New York that was her refuge, a source of inspiration and where she would eventually die, I could see that glorious landscape represented in the multi-hued pieces that formed her canvas: a red tulip-like shape, blobs of blue that represented a lake, a road that led to the farm along with white clouds, a green tree, an azure sky and yellow sun. And off to the side is a human figure taking it all in.

Despite the compact running time, it is easy to feel that you have come to know—and likely admire—Elizabeth Murray. So, mission accomplished.

Also worth seeing is “The 100 Years Show,” named in honor of its too-long-unsung painter subject, Carmen Herrera, who is shown celebrating her centennial birthday by the time this half-hour companion short concludes. Prepare to be appalled yet again at how rampant misogyny along with world events kept this Havana-born, New York-based artist—whose dynamic yet minimalist geometric designs are energized by the ingenious pairing of simple shapes and vivid colors that can hold its own against the likes of Frank Stella—from getting her full due as a talent until she was 94.

Too bad her first solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum recently closed. But just seeing this small sampling of her output and meeting the no-nonsense Herrera herself, who doesn’t let her need for a wheelchair interfere with her desire to create (as she wisely states, “You cannot talk about art. You have to art about art”), will likely make you a devoted fan.