The director Tim Burton wages a valiant battle to show us new and wonderful things. In a Hollywood that placidly recycles the same old images, Burton uses special effects and visual tricks to create sights that have never been seen before. That is the good news. The disappointment is that Burton has not yet found the storytelling and character-building strength to go along with his pictorial flair.

That was true even of his “Batman,” which was 1989’s box office champion, but could have been a better film, I believe, if there had been anyone in it to inspire our emotional commitment. Even comic characters can make us care. Unlike Richard Donner’s original “Superman,” which actually had a heart beneath its special effects, Burton’s “Batman” occupied a terrain in which every character was a grotesque of one sort of another, and all of their actions were inspired by shallow melodramatic motivations.

That movie was stolen by a supporting character – Jack Nicholson’s Joker – and now comes “Edward Scissorhands,” another inventive effort in which the hero is strangely remote. He is intended, I think, as an everyman, a universal figure like one of the silent movie clowns, who exists on a different plane from the people he meets in his adventures. One problem is that the other people are as weird, in their ways, as he is: Everyone in this film is stylized and peculiar, so he becomes another exhibit in the menagerie, instead of a commentary on it.

The movie takes place in an entirely artificial world, where a haunting gothic castle crouches on a mountaintop high above a storybook suburb, a goofy sitcom neighborhood where all of the houses are shades of pastels and all of the inhabitants seem to be emotional clones of the Jetsons. The warmest and most human resident of this suburb is the Avon lady (Dianne Wiest), who comes calling one day at the castle – not even its forbidding facade can deter her – and finds it occupied only by a lonely young man named Edward (Johnny Depp).

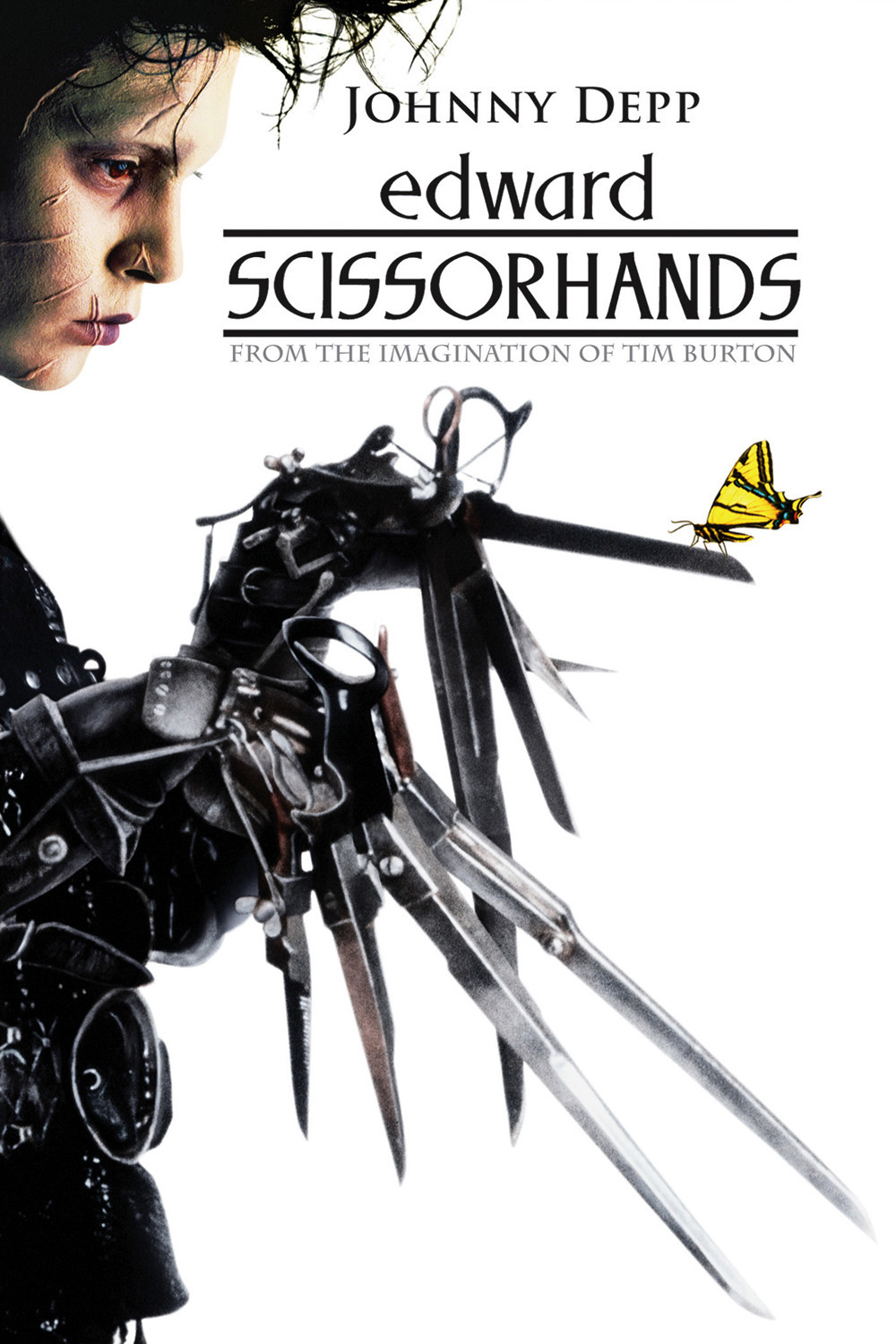

His story, told in a flashback, is a sad one. He was created by a mad inventor (Vincent Price), who was almost finished with his task when he died, leaving Edward with temporary scissors in place of real hands. One look at Edward and we see that scissors are inconvenient substitutes for fingers: His face is a mass of scars, and he tends to shred everything he tries to pick up.

The Avon lady isn’t fazed. She bundles Edward into her car and drives him back down the mountain to join her family, which includes daughter Kim (Winona Ryder) and husband Bill (Alan Arkin).

The neighbors in this suburb are insatiably curious, led by a nosy neighbor named Joyce (Kathy Baker). The movie then develops into a series of situations that seem inspired by silent comedy, as when Edward tries to pick up a pea.

Successful satire has to have a place to stand, and a target to aim at. The entire world of “Edward Scissorhands” is satire, and so Edward inhabits it, rather than taking aim at it. Even if he lived in a more hospitable world, however, it is hard to tell what satirical comment Edward would have to make, because the movie makes an abrupt switch in his character about two-thirds of the way through. Until then he’s been a gentle, goofy soul, a quixotic outsider. Then Burton and his writer, Caroline Thompson, go on autopilot and paste in a standard Hollywood ending.

You know what that is. The hero and the villain meet, there is a deadly confrontation, and no prizes for guessing who wins.

Except in pure action films, situations used to be solved by dialogue and plot developments. No more. Now someone is killed, and that’s the solution, and the movie is over. In “Edward Scissorhands,” the villain is a neighborhood lout named Jim (Anthony Michael Hall), who doesn’t like guys with scissors for hands, and picks on Edward until finally there is a trumped-up fight to the finish up at the castle.

This conclusion is so lame it’s disheartening. Surely anyone clever enough to dream up Edward Scissorhands should be swift enough to think of a payoff that involves our imagination.

All of Burton’s movies look great. “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure” was an unalloyed visual delight, and so was “Beetlejuice,” and “Batman” gave us a Gotham City that was one of the most original and atmospheric places I’ve seen in the movies. But shouldn’t there be something more? Some attempt to make the characters more than caricatures? All of the central characters in a Burton film – Pee-wee, the demon Betelgeuse, Batman, the Joker or Edward Scissorhands – exist in personality vacuums; they’re self-contained oddities with no connection to the real world. It’s saying something about a director’s work when the most well-rounded and socialized hero in any of his films is Pee-wee Herman.