The opening shots inform us with authority that “DIVA” is the work of a director with an enormous gift for creating visual images. We meet a young Parisian mailman. His job is to deliver special-delivery letters on his motor scooter. His passion is opera, and, as “DIVA” opens, he is secretly tape-recording a live performance by an American soprano. The camera sees this action in two ways. First, with camera movements that seem as lyrical as the operatic performance. Second, with almost surreptitious observations of the electronic eavesdropper at work. His face shows the intensity of a fanatic: He does not simply admire this woman, he adores her. There is a tear in his eye. The operatic performance takes on a greatness, in this scene, that is absolutely necessary if we’re to share his passion. We do. And, doing so, we start to like this kid.

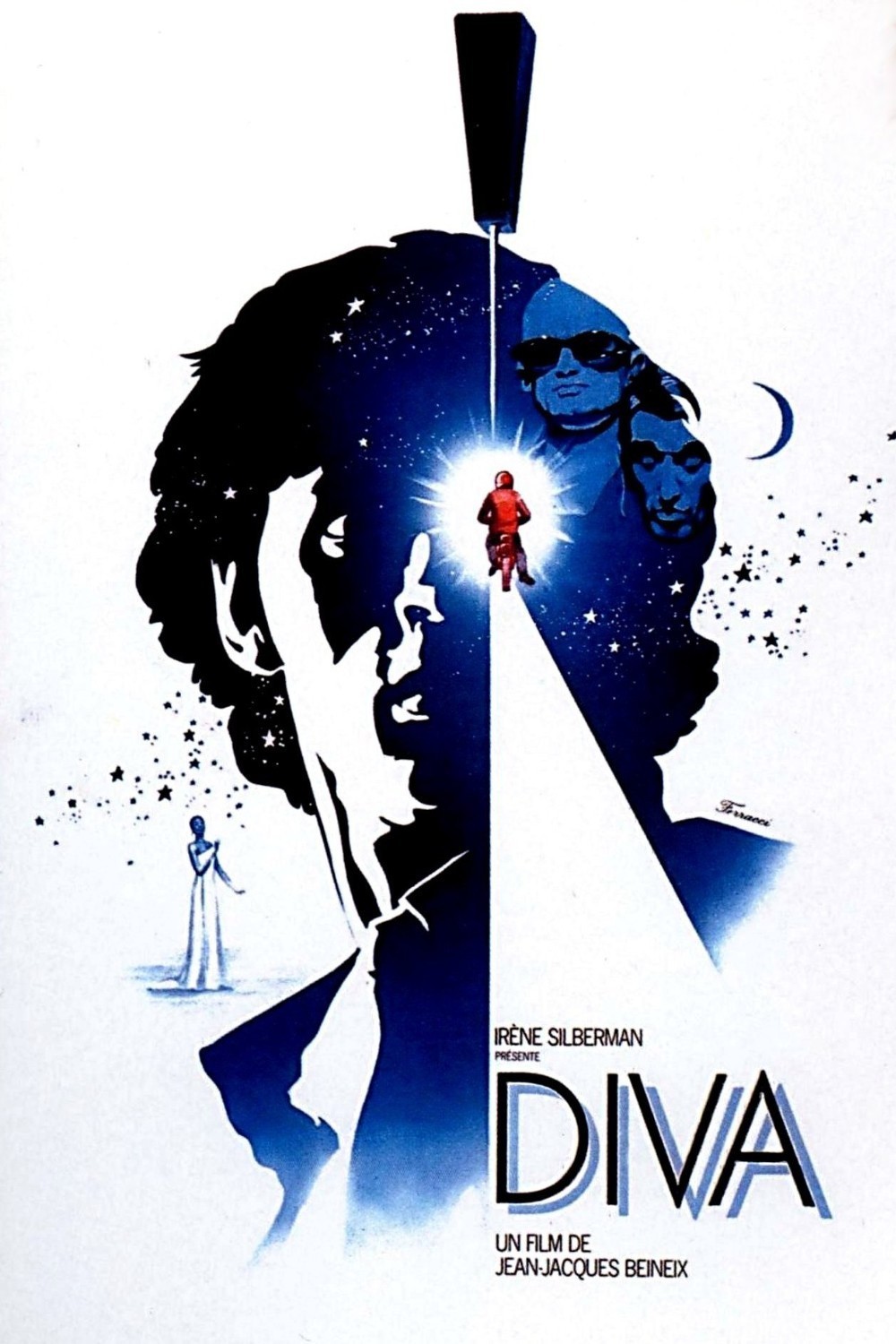

He is played by Fredric Andrei, an actor I do not remember having seen before. But he could be Antoine Doinel, the subject of “The Four Hundred Blows” and several other autobiographical films by Truffaut. He has the same loony idealism, coexisting with a certain hard-headed realism about Paris. He lives and works there, he knows the streets, and yet he never quite believes he could get into trouble. “DIVA” is the story of the trouble he gets into. It is one of the best thrillers of recent years but, more than that, it is a brilliant film, a visual extravaganza that announces the considerable gifts of its young director, Jean-Jacques Beineix. He has made a film that is about many things, but I think the real subject of “DIVA” is the director’s joy in making it. The movie is filled with so many small character touches, so many perfectly observed intimacies, so many visual inventions from the sly to the grand that the thriller plot is just a bonus. In a way, it doesn’t really matter what this movie is about; Pauline Kael has compared Beineix to Orson Welles and, as Welles so often did, he has made a movie that is a feast to look at, regardless of its subject.

But to give the plot its due: “DIVA” really gets under way when the young postman slips his tape into the saddlebag of his motor scooter. Two tape pirates from Hong Kong know that the tape is in his possession, and, since the American soprano has refused to ever allow any of her performances to be recorded, they want to steal the tape and use it to make a bootleg record. Meanwhile, in a totally unrelated development, a young prostitute tape-records accusations that the Paris chief of police is involved in an international white-slavery ring. The two cassette tapes get exchanged, and “DIVA” is off to the races.

One of the movie’s delights is the cast of characters it introduces. Andrei, who plays the hero, is a serious, plucky kid who’s made his own accommodation with Paris. The diva herself, played by Wilhelmenia Wiggins Fernandez, comes into the postman’s life after a most unexpected event (which I deliberately will not reveal, because the way in which it happens, and what happens, are enormously surprising). We meet others: A young Vietnamese girl who seems so blasŽ in the face of Paris that we wonder if anything truly excites her; a wealthy man-about-town who specializes in manipulating people for his own amusement; and a grab bag of criminals.

Most thrillers have a chase scene, and mostly they’re predictable and boring. DIVA’s chase scene deserves ranking with the all-time classics, “Raiders of the Lost Ark“, “The French Connection“, and “Bullitt“. The kid rides his motorcycle down into the Paris Metro system, and the chase leads on and off trains and up and down escalators. It’s pure exhilaration, and Beineix almost seems to be doing it just to show he knows how. A lot of the movie strikes that note: Here is a director taking audacious chances, doing wild and unpredictable things with his camera and actors, just to celebrate moviemaking.

There is a story behind his ecstasy. Jean-Jacques Beineix has been an assistant director for ten years. He has worked for directors ranging from Claude Berri to Jerry Lewis. But the job of an assistant director is not always romantic and challenging. Many days, he’s a glorified traffic cop, shouting through a bullhorn for quiet on the set, and knocking on dressing room doors to tell the actors they’re wanted. Day after day, year after year, the assistant director helps set up situations before the director takes control of them. The director gives the instructions, the assistant passes them on. Perhaps some assistants are always thinking of how they would do the shot. Here’s one who finally got his chance.