Kevin Spacey believes he was born to play Bobby Darin. I believe he was born to play more interesting characters, and has, and will, but I can see his point. He looks a little like Darin and sounds a lot like him, and apparently when he was growing up he formed one of those emotional connections with a performer where admiration is mixed with pity.

Darin’s own emotional connection was apparently with Frank Sinatra, a pop singer he hoped to displace. That wasn’t going to happen; there is a point beyond which talent cannot be extended into genius. He died young, at 37, having lived most of his life on borrowed time. After rheumatic fever at 7, he wasn’t expected to live past 15. That he found 22 more years, had great success and made recordings that are still popular today is an achievement, but not one that makes a biopic necessary, unless the filmmaker is moved by a personal obsession.

Kevin Spacey was, and “Beyond the Sea” is at least as much about Spacey playing Darin as about Darin himself. Is Spacey too old to be convincing as a singer in his teens, 20s and 30s? Yes, but not too old to play an actor in his 40s who feels driven to play such a role. Perhaps there are parallels. Spacey has struggled, been misunderstood, had triumphs and disasters, has recently been the target of malicious coverage in the British press (his sin was to presume to contribute to the London stage even though he is a Movie Star).

In his own best work, Spacey has achieved genius; he is better as an actor than Darin ever was as a singer, but there must have been a time when Spacey identified strongly with Darin’s disappointments and defeats, and “Beyond the Sea” is about those feelings.

It is also probably relevant that Spacey, in preparing the project, knew something we could not guess: He is a superb pop singer. In a rash ad lib on “Ebert & Roeper,” I said I thought he was probably even a better singer than Darin. A statement like that has an apples-and-oranges foolishness; Darin was himself and nobody else ever will be, and it’s enough to observe that although many actors think they are wonderful singers, Spacey is correct.

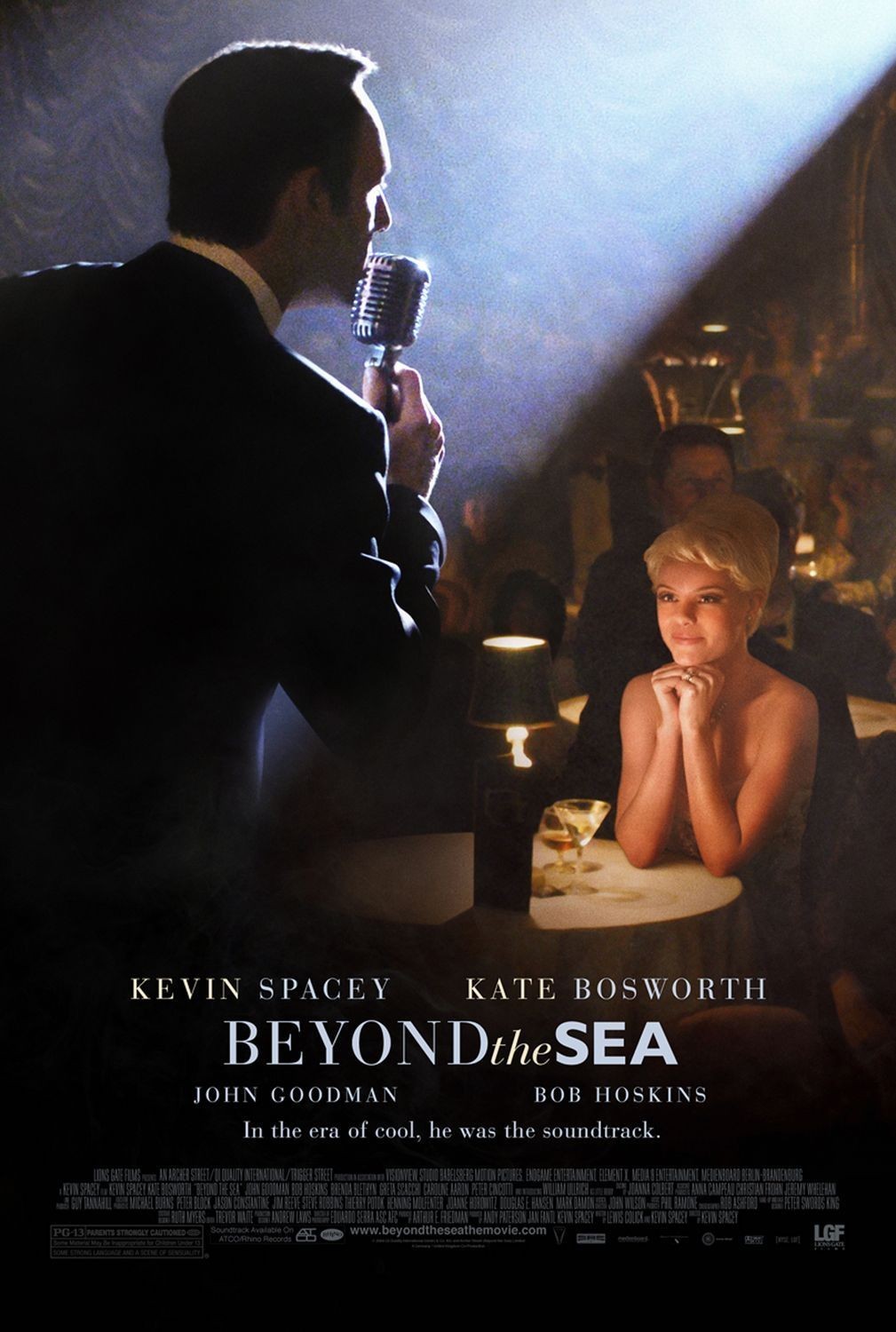

He constructs the picture as a film within a film, to provide an explanation for the spectacle of an older man playing a much younger one. The film begins with Darin onstage at the Copacabana nightclub, and then pulls back to reveal that we’re on a sound stage; the adult Darin is confronted by himself as a young boy, arguing that he’s gotten it all wrong, and in a weird way the whole movie will be an argument among the various ages of Bobby Darin. There is a parallel with “De-Lovely,” in which the ancient Cole Porter reviews a musical about his life; in both cases, the POV is essentially posthumous.

Darin as a boy is the darling of his mother (Brenda Blethyn) and sister Nina (Caroline Aaron), although his relationship with them is not quite what he believes. Nina’s husband, Charlie (Bob Hoskins), helps start his career, a manager (John Goodman) signs aboard and, with big teeny-bopper hits like “Splish Splash,” he becomes a star.

Darin hungers to grow, and moves into the mainstream of popular music with hits like “Mack the Knife” and “Beyond the Sea.” On a movie set, he falls in love with Sandra Dee (Kate Bosworth) and marries her, at a time when their careers were both soaring. The marriage goes wrong for reasons that seem to have more to do with biopic conventions than real life; their careers keep them apart, etc., although there is a moment with the hard truth of “A Star Is Born” when Darin is nominated for an Oscar, loses, goes ballistic and screams: “Warren Beatty is there with Leslie Caron and I’m there with Gidget!”

Darin’s career collapse led at one point to exile in a house trailer, and then to a comeback in which he tried to cross over into politically-conscious acoustic folk singing, which was not a good fit for his talent. (“Sing ‘Dream Lover!'” the jerks in the audience shouted. “Sing ‘Splish Splash!'”) His Vegas debut flops, but he returns in triumph after re-staging his show to include a black gospel choir, which brings a lot of energy onto the stage. He is advised of audiences, “Remember — they hear what they see,” and he nods at this wise insight, although I am not sure exactly what it means.

Bobby Darin’s life provides a less-than-perfect template for a biopic because he achieved success up to a certain point, then failed, then did not really have much of a comeback, then died young. Not precisely the inspirational ascent of a biographical Everest. But the movie possesses genuine feeling because Spacey is there with Darin during all the steps of this journey, up and down, all the way into death. Not all stories have happy endings. Not all lives have third acts. This was a life, too, and although it was a disappointment, it also contained more success and maybe even more happiness than Darin could have reasonably expected at age 15, his presumed cut-off date. What I sensed above all in “Beyond the Sea” was Spacey’s sympathy with and for Bobby Darin. There have been biopics inspired by less worthy motivations.