There’s a scene in “Beyond the Lights” that hit me with unexpected, eye-watering emotional force. Noni (Gugu Mbatha-Raw), a hugely popular R&B singer with a massive fan base, stands in the bathroom mirror of a remote island hotel resort where few know her fame. Slowly, and seemingly on a whim, she starts to remove her trademark straight purple weave, the strands falling into the sink as she fashions the curly hair underneath into a shorter, more natural style. Writer-director Gina Prince-Bythewood shoots this with little fanfare, almost nonchalantly, yet I was overwhelmed by the scene’s quiet power. It exists on so many levels, and I responded tearfully to each of them because, by this point, “Beyond the Lights” had shown me so much of this character’s internal and external struggle that I felt I knew her. I understood that this was the first time Noni probably had any say in her appearance since she became famous. The simple act of choosing how she presented herself was a rebellious moment of true liberation, a crucial first step in her self-healing process.

A few minutes later, “Beyond the Lights” goes for a grander, operatic moment that serves as a more blatant, yet equally effective reiteration of Noni’s character rebirth. But I admired and respected Prince-Bythewood’s faith in the audience’s ability to pick up subtler nuances. As writer-director of “Disappearing Acts,” “The Secret Life of Bees,” and her masterpiece, “Love and Basketball,” Prince-Bythewood specializes in characters who are as complex as those residing in literature. The people she writes have lives that exist separately from their romantic and societal entanglements. The audience tags along with each of her creations down their separate pathways, so when a character reacts to a certain situation, we know why. Sometimes we can even predict what they’ll do before they act.

Prince-Bythewood is unafraid of both the quiet moment and those of melodramatic grandiosity. The trailers for her films do them quite a disservice, for they contain scenes that, out of context, appear hokey, but in context bear an effectiveness that stings and stuns. “Beyond the Lights” makes unapologetically damning statements about the music industry’s treatment of women, yet it never feels preachy. It strikes a risky, though successful balancing act between being immensely entertaining as a musical feature and making dramatic, important statements about depression, self-worth and female empowerment.

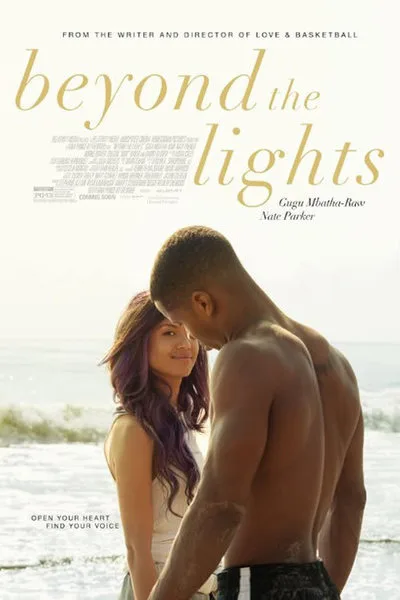

At the center of “Beyond the Lights” is Gugu Mbatha-Raw, who does her own singing and embodies Noni so fiercely that she sears the screen. This is a star-making performance; Noni is a complete 180-degree turn from the titular character she played in “Belle.. “Beyond the Lights” gives her complicated song and dance numbers, scenes of immense strength and overpowering weakness, and a romance that plays like a less tragic “A Star is Born” or “Mahogany,” had “Mahogany” been any good. This is an incredibly rich role and Mbatha-Raw commands every second she’s onscreen.

Assisting her is Nate Parker, who plays Kaz, her love interest and bodyguard, and Minnie Driver, who plays Noni’s driven stage mother, Macy Jean. Macy Jean is the meanest, most complex stage mother since Mama Rose in “Gypsy.” Kaz is soulful and suave, yet possesses a vulnerability that is sometimes comic and always sweet. Both actors give outstanding performances and have scenes where they rise to the challenge and match Mbatha-Raw’s ferocity. Prince-Bythewood’s script is extremely charitable, giving Driver a knockout of a speech about her struggles in England as “a poor White mother with a Black baby” and allowing Parker an equal share of the film’s most powerful moment with Mbatha-Raw.

“Beyond the Lights” opens with Macy Jean taking the young Noni (a fantastic India Jean-Jacques) to a talent contest. Noni sings Nina Simone’s “Blackbird,” which becomes her unofficial theme song. “Why you wanna fly, Blackbird?” Noni sings. “You ain’t ever gonna fly.” Noni wins second place when she clearly deserves the winning trophy, and Macy Jean not only makes a scene but she cruelly forces the briefly proud Noni to discard the trophy in the street. Prince-Bythewood has Noni sing “Blackbird” again later at the island resort, an adult version mirroring her youthful one in both style and situation. Mbatha-Raw replaces the innocence of Jean-Jacques’ version with the adult Noni’s sense of cathartic release, and the effect is hauntingly beautiful.

Before she gets to that romantic island getaway, which she shares with Kaz, Noni has to navigate a horrific amount of the sexist behavior that comes with being a singer of hooks in rap songs and appearances at the BET and MTV awards. Noni is dressed to sell sex, and she sings about it with Rihanna-like aplomb. She’s teamed with an Eminem-like rapper whom she’s dating, and her success is at first directly tied to his. “Beyond the Lights” paints a dark picture of the music industry; at one point, on live TV, the rapper practically sexually assaults Noni because she’s “being disrespectful.” Kaz leaps to her aid, and his chivalry doesn’t go unrewarded.

“We’re practically babysitters,” Kaz’s police officer dad (Danny Glover) tells him. Dad wants Kaz to run for office, and we spend enough time with Parker and his subplot to flesh out his character. This enriches his romance with Noni, a romance that Dad thinks is detrimental. It’s to Prince-Bythewood’s credit that Kaz’s first run-in with Noni is far from a Meet Cute. She’s on a balcony about to kill herself, and Kaz is called upon to do his job. This scene is so delicately written that the slightest misstep would have made it collapse. Parker’s old-school leading man charm is akin to Billy Dee Williams’ in “Lady Sings the Blues”; coupled with Mbatha-Raw’s naked vulnerability, it helps turn some potentially ripe melodramatic dialogue into one of the most powerfully rendered two-hander scenes of 2014.

“Beyond the Lights” is an epic movie, crammed with comedy, drama, music and romance, yet it never feels overstuffed. It makes its important statements while being immensely entertaining. At the Toronto Film Festival premiere I attended, the director stated she cut the film’s extremely hot sex scene down to obtain a PG-13 because she wanted teenage girls to experience the film’s strong female empowerment vibe. The film has that, and it has two Black people in a romance, but that doesn’t mean it’s just for women or African-Americans. “Beyond the Lights” includes elements that speak to those groups within a much bigger scope that appeals to all viewers.

During the Q&A after the film’s TIFF screening, Prince-Bythewood talked about how difficult it was to get this film made. Given her talent, one should find this hard to believe. Hopefully, “Beyond the Lights” will draw the attention to her that “Love and Basketball” should have. That film has a permanent place in my heart, and while “Beyond the Lights” won’t replace it, there’s enough room in there for it to nest. I haven’t been able to shake this movie, or Gugu Mbatha-Raw’s performance, since I saw it two months ago. This is a fantastic film. Drop what you’re doing and go see it.