Old Jimmie Langdon, the impresario who taught the young Julia Langdon much of what she knows about the world, refers at one point to “What civilians call the real world.” Theater people know better. All the world’s a stage, and Julia is but a player on it. At one point, when she’s asked for a loan, she replies with the same speech she used earlier in a play. Her marriage is “in name only.” Even her extramarital affair is a performance; her lover, Lord Charles, finally confesses, “I play for the other side.” Her son, Roger, says: “You have a performance for everybody. I don’t think you really exist.”

In “Being Julia,” she departs from the playwright’s lines and improvises a new closing act right there on the stage, and it’s appropriate that her professional and personal problems should be resolved in front of an audience. Like Margo Channing, the Bette Davis character in “All About Eve,” Julia draws little distinction between her public and private selves. She lives to be on the stage, and when, at 45, she perceives that her star is dimming, she fights back with theatrical strategies.

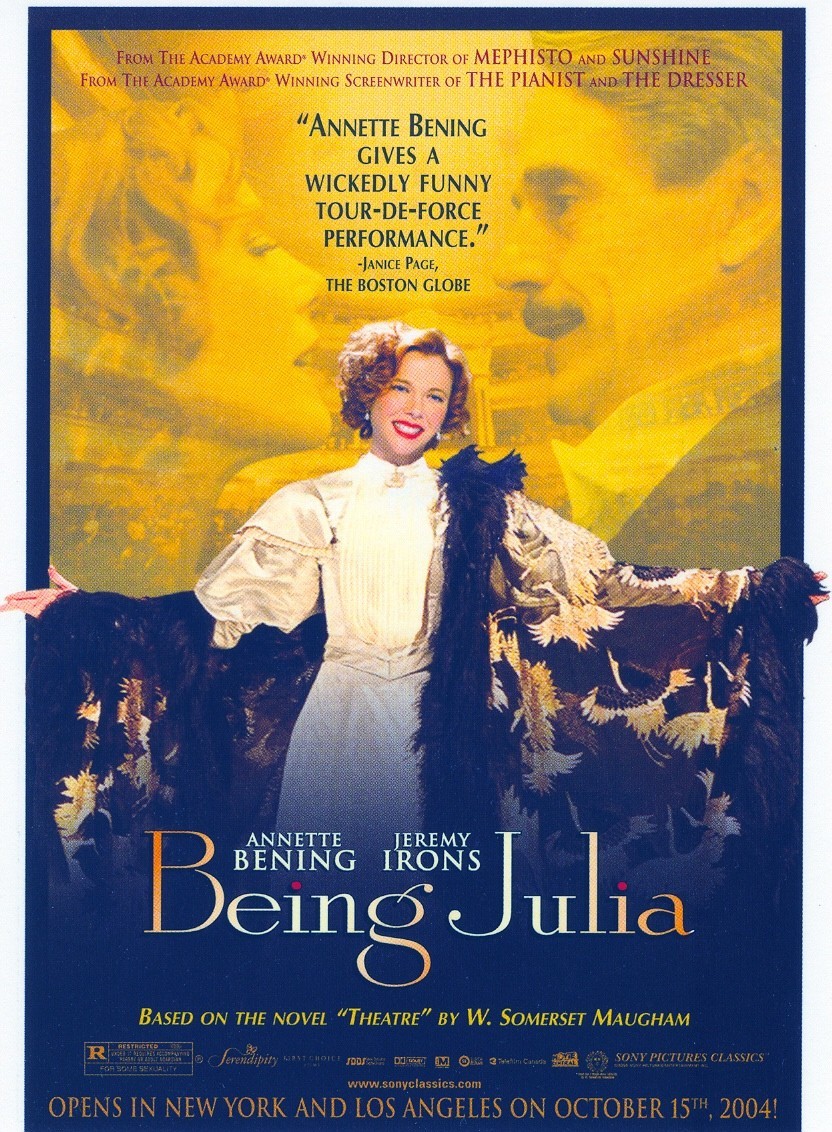

Annette Bening plays Julia in a performance that has great verve and energy, and just as well, because the basic material is wheezy melodrama. “All About Eve” (1950) breathed new life into it all those years ago, but now it’s gasping again. The film is based on Theatre, a 1937 novel by W. Somerset Maugham that was not one of his few great works, and has been adapted by a director and a writer who have separately created much more important fictions about the theater. Istvan Szabo directed “Mephisto,” with its brilliant performance by Klaus Maria Brandauer as an actor who sells out to the Nazis to protect his career, and Ronald Harwood wrote “The Dresser,” one of the most knowledgeable of backstage plays.

Here they all seem to have followed Maugham into a soap opera. Bening is fresh and alive (is there another actress who smiles and laughs so generously and naturally?), but she’s surrounded by stock characters. Jeremy Irons plays her husband and producer, Michael, who turns a blind eye to her lover, Lord Charles (Bruce Greenwood), and why should he not, since Charles actually decides to break up with her because of all the gossip — and isn’t gossip surely the best reason to have an affair with an actress?

They are all in the middle of an enormously successful play, but Julia has tired of it, complaining that the world is too much with her, she is weary and bored, she thinks she may retire. Circling her like moons, reflecting her light, are not only Michael and Charles but her loyal dresser Evie (Juliet Stevenson), her hopeful lesbian admirer Dolly (Miriam Margolyes), and the ghost of old Jimmie (Gambon), who advises for practical reasons that she sleep with her young leading man: “If that doesn’t improve your performance, then nothing will.”

What happens instead is that she meets the callow young American theatrical accountant, Tom Fennel (Shaun Evans), a man as exciting as the seed after which he is named. He’s seen all of her plays — some of them three times! — and Julia is flattered, not so much by his praise as by sex with a man half her age. In a world with few secrets, Lord Charles frets: “I trust she doesn’t tell the boy she loves him — that’s always fatal.”

She sort of does and it sort of is, especially after the arrival of the young ingenue Avice Crichton (Lucy Punch), in the Eve Harrington role. Not only does Avice feel warmly toward Tom, but she also sparks interest in old Michael, Julia’s husband, whose genitals may be able to revive for a farewell tour.

All of this is fitfully entertaining, but it only seems to be happening for the first time to the Bening character. The others seem trapped in loops, as if they’ve traveled these cliches before. All comes to a head during rehearsals for a new play in which Avice seems to have better lines and staging than Julia. (“I’m going to give my all in this part!” she gushes to Julia, who replies, “Mustn’t be a little spend-thrift.”) It’s by departing from the staging and the lines and improvising in an entirely different direction that Julia delivers Avice’s comeuppance.

But it doesn’t happen that way in the theater. An actor may improvise a line or two, or a bit of business, or communicate in an occult way with the audience, or if he’s Groucho Marx or Alfie even address us directly, but is it possible to improvise an entire act with the other actors on stage, and somehow incorporate them in such a way that they’re not left standing there and gawking at you?

I don’t think so. I think the movie leads up to a denouement that would work only if the improvisation (as it is here) were carefully scripted and rehearsed. There’s never the feeling that poor Avice is really out to sea, because even her discomfiture seems carefully blocked.

I liked the movie in its own way, while it was cheerfully chugging along, but the ending let me down; the materials are past their sell-by date and were when Maugham first retailed them. The pleasures are in the actual presence of the actors, Bening most of all, and the droll Irons, and Juliet Stevenson as the practical aide-de-camp, and Thomas Sturridge, so good as Julia’s son that I wonder why he wasn’t given the role of her young lover.