Burt and Verona are two characters rarely seen in the movies: thirtysomething, educated, healthy, self-employed, gentle, thoughtful, whimsical, not neurotic and really truly in love. Their great concern is finding the best place and way to raise their child, who is a bun still in the oven. For every character like this I’ve seen in the last 12 months, I’ve seen 20, maybe 30, mass murderers.

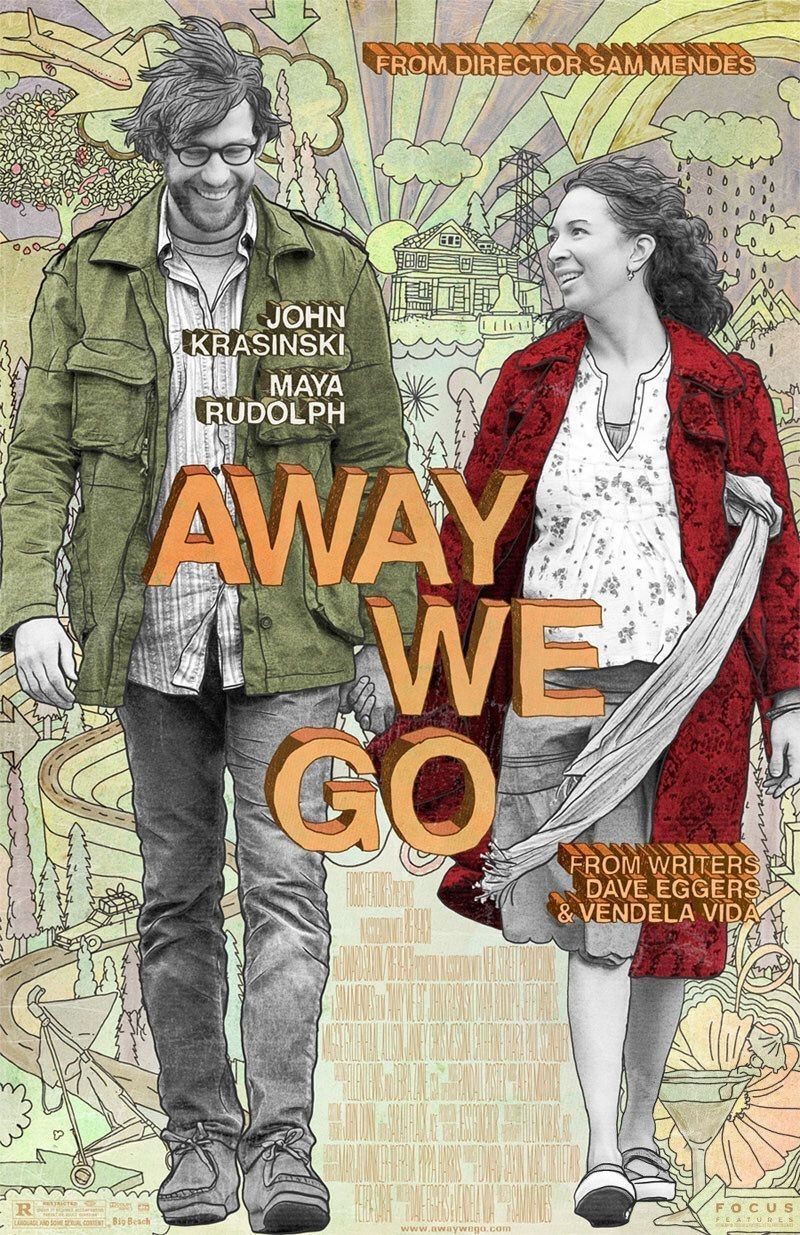

Sam Mendes’ “Away We Go” is a film for nice people to see. Nice people also go to “Terminator Salvation,” but it doesn’t make them any nicer. “Away We Go” opened last week in New York and Los Angeles, and now rolls out after lukewarm reviews accusing Verona and Burt of being smug, superior and condescending. These are not sins if you have something to be smug about and much reason to condescend.

Are the supporting characters caricatures or simply a cross-section of the kinds of grotesques we usually meet in movies? I use the term grotesque as Sherwood Anderson does in Winesburg, Ohio: a person who has one characteristic exaggerated beyond all scale with the others.

Burt (John Krasinski) and Verona (Maya Rudolph) live not far from his parents, in an underheated, shabby home with a cardboard-covered window. “We don’t live like grown-ups,” Verona observes. It’s not that they can’t afford a better home, as much that they are stalled in an impoverished student lifestyle. Now that they’re about to become parents, they can’t keep adult life on hold.

“Away We Go” is about an unplanned odyssey they take around North America to visit friends and family, and essentially do some comparison shopping among lifestyles. Her parents are dead, so they begin with his: Gloria (Catherine O’Hara) and Jerry (Jeff Daniels). The parents truly are self-absorbed, and have no wish to wait around to welcome their first grandchild. They’re moving to Antwerp.

Verona is of mixed race, and Gloria asks her conversationally, “Will the baby be black?” Is this insensitive? Why? Parents on both sides of an interracial couple would naturally wonder, and the film’s ability to ask the question is not racist, but matter of fact in a America slowly growing tolerant. In moments like that, the married screenwriters, Dave Eggers and Vendela Vida (both novelists and magazine publishers), reflect a society in which race is no longer the primary defining characteristic.

After the parents vote for Belgium, Burt and Verona head for Phoenix and a visit with her onetime boss Lily (Allison Janney) and her husband Lowell (Jim Gaffigan). Lily is a monster, a daytime alcoholic whose speech is grossly offensive, and her husband and children in shock. They flee to Madison, where Burt’s childhood friend Ellen (Maggie Gyllenhaal) has changed her name to “LN” and become one of those rigid campus feminists who have banned human nature from their rule book.

Then it’s off to Montreal for friends from college, Tom and Munch (Chris Messina and Melanie Lynskey), who are unhappily convinced they’re happy. And next down to Miami and Burt’s brother, whose wife has abandoned her family. There’s not a single example of healthy parenting in the lot of them.

The almost perfect relationship of the unmarried Verona and Burt seems to survive inside a bubble of their own devising, and since they can blow that bubble anywhere, they of course find the perfect home for it, in a scene of uncommon sunniness. They have been described as implausibly ideal, but you know what? So are their authors, Eggers and Vida. They are thirtysomethings. With two children. Novelists and essayists. He publishes McSweeney’s, she edits the Believer.

They are playful but also socially committed. Consider his wonderful project “826 Valencia,” a nonprofit storefront operation in San Francisco, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Seattle, Boston and Ann Arbor, Mich. It runs free tutoring and writing workshops for young people from ages 6 to 18. The playful part can be seen in San Francisco, where the front of the ground floor is devoted to a Pirate Store. Yes. With eye patches, parrot’s perches, beard dye, peg legs, planks for walking — all your needs.

I submit that Eggers and Vida are admirable people. If their characters find they are superior to many people, well, maybe they are. “This movie does not like you,” sniffs Tony Scott of the New York Times. Perhaps with good reason.