The new “Annie” is getting kicked up and down Critic’s Row like an unwanted orphan, but if you see it with a big audience you’ll experience an emotion entirely different from the one being described in many reviews: unabashed cheer.

This new version of the Broadway musical is the first since the 1999 ABC TV version, and the only theatrical movie version since the 1982 John Huston picture that starred Aileen Quinn, Albert Finney and Carol Burnett. (The ’99 TV version is excellent, by the way—well worth seeking out; it’s easily the best thing director Rob Marshall has been associated with.) Judged purely in terms of its production and direction, this latest “Annie” is inferior to its predecessors; director Will Gluck, of TV’s “The Marshalls” and “Andy Richter Controls the Universe,” has envisioned it as a repository of 2014 music and musical performance cliches, the actors cavorting through indifferently composed widescreen vistas, and singing in voices that have been heavily AutoTuned.

And yet a quality of willfully naive optimism—of repeatedly neglected and disappointed goodness hauling itself up off the pavement, summoning a smile, and singing out—shines through anyway, and you might or might not be amazed to learn that it cancels out the movie’s many flaws. Bottom line: this “Annie” is a gigantic smiley face, arriving on screens at the tail end of one of the most miserable years in recent American history—a year whose uninterrupted flood of not just bad but national-identity-challenging, often racially toxic news made even some of the most optimistic among us want to crawl into bed, pull the covers up, and stay there until the calendar rolled over.

And now here’s little Quvenzhané Wallis, the youngest Oscar nominee in history, stepping into shoes that have previous been filled only by red-haired Caucasian girls, and striding through a present day New York City enclosed and in some ways superseded by the virtual world of the Internet and cell phones and satellite locators, singing and dancing opposite an African-American version of Daddy Warbucks, a self-made cell phone magnate played by Jamie Foxx—and it’s still “Annie,” a deeply American story about reinvention and striving, survival and dreams.

This Annie is a foster child living in an apartment with other foster children rather than an “orphan” as described in other versions. And she’s been situated within a universe that’s contemporary, but which nonetheless connects forcefully with the Depression-era landscapes of the stage musical, the ’99 and ’82 films, and the source material that inspired all them, Harold Gray’s comic strip. All were about maintaining one’s optimism in the face of personal misfortune exacerbated by a Grand Canyon-vast gap between rich and poor; they were about the difficulty of staying sensible, and sensitive, in world in which everyone but the very wealthy had to struggle constantly, and deny themselves pleasures, and some essentials. This is also the story of a heroine possessed of a specific kind of optimism: Annie’s signature ballad “Tomorrow” is not sung by an ignorant, stupid or naive child, but one who’s aware of how miserable things can get and how cruel the wheels of fate can be, yet squares her shoulders against whatever life might throw at her, and continues to dream of, and pursue, a better future.

Wallis is the first Annie to bring something both culturally and personally new to this role, and the film knows it: it even sets up her appearance by having a more typical Annie anchor an opening scene in a classroom, then letting Wallis take over (as, literally, a different Annie who happens to have the same name) and school her teacher and students with a lesson set to music with a bubble-gum R&B back-beat. Wallis seizes control of the film through sheer charm.

But the really beautiful thing is, like Foxx’s performance as Stacks—basically a germophobic Michael Bloomberg, shrinking from human contact and busting out antibacterial hand wash after every meet-and-greet—the point is not to rebuke any of the previous versions of “Annie,” but to say something more like, “Look, we changed the color of the leads, and revised the music to make it modern, and changed the plot so that the complications and resolutions are filtered through new technology, and yet it’s still the story you remember, with the same themes and messages.”

The movie is sharp in grasping how the plot of “Annie,” indeed most dramatic public interaction these days, must be reconfigured and re-thought, to take camera phones, YouTube, satellite tracking, and other technology into account. Stacks’ bid to be mayor of New York is DOA a the start of the movie, thanks to his extremely unlikable queasiness about human contact, but it’s resuscitated when a cell phone video of him rescuing Annie from a near-hit-and-run accident goes viral. (His advisor’s attempts to recreate this random event for political gain have a Preston Sturges feeling.) The movie is filled with knowing, playful acknowledgments that experience is becoming more theoretical than physical, such as the “starry sky” on the wall of Annie’s bedroom at Stack’s place, which is really a series of video screens; yet such touches only confirm that, no matter how physical or virtual the world becomes, love and the absence of love are real, and can save or wound us.

When you consider that such a project could have easily collapsed under the weight of its own self-created mandate, the film’s easygoing nature seems all the more remarkable. “Annie” is light on its feet, frothy, and always insistently, at times provocatively kind, determined to melt grumpy hearts like marshmallows.

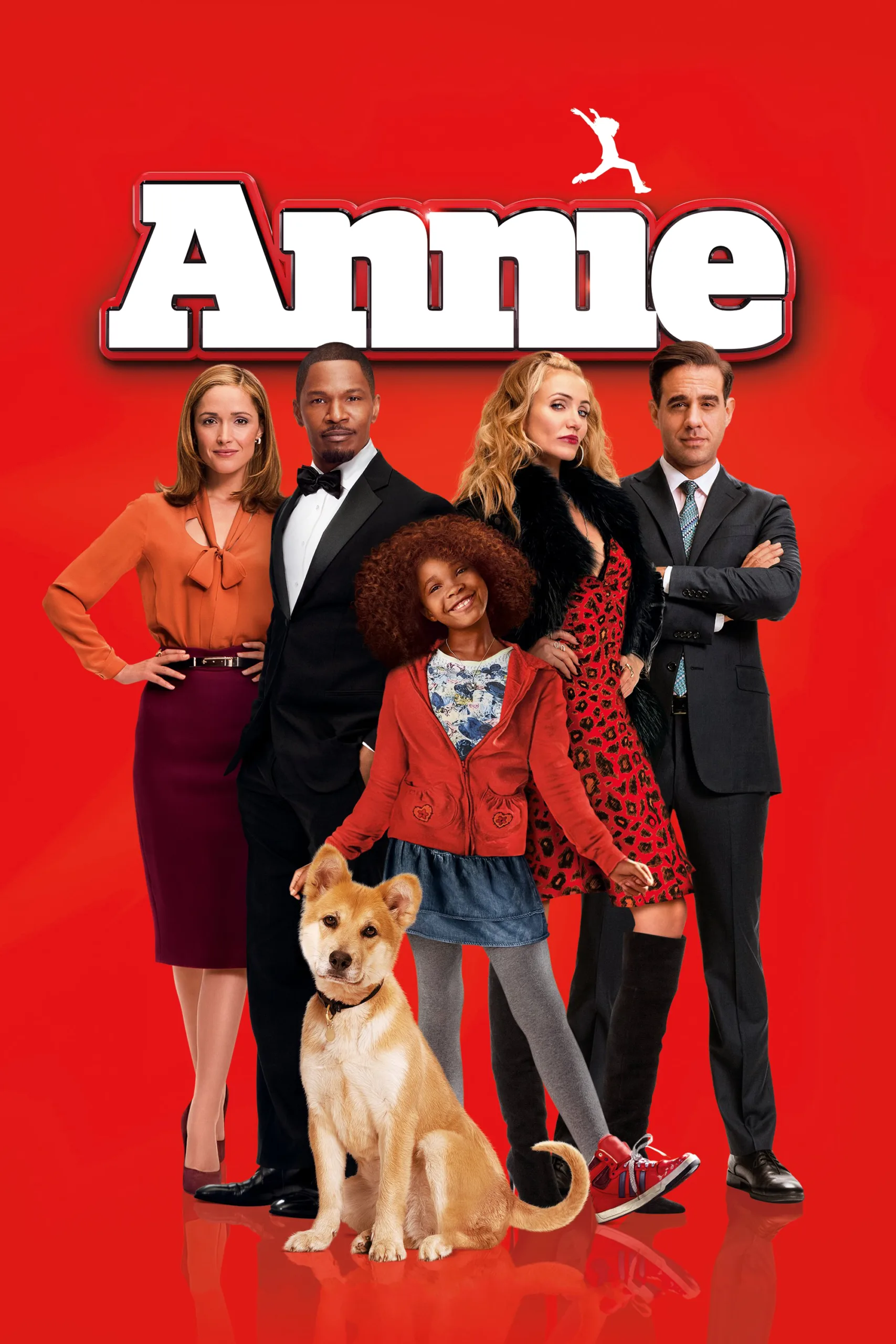

Wallis is impossible not to like; she plays Annie as she should be played, as a smart, tough kid without an unkind thought in her head, and when her resolve finally crumbles in the face of one disappointment too many, your heart sinks with hers. The supporting cast is equally fine. The cream of the crop includes Foxx, a handsome, brawny leading man whose acting convinces us that Stacks might actually be terrified of the world, and his own heart; Rose Byrne as Grace, Stack’s right-hand-woman and living, breathing conscience (and, of course, unacknowledged romantic option); David Zayas as Lou, a bodega owner who’s kind to Annie and has a crush on her harridan foster mom, and Bobby Cannavale as Guy, Stacks’s campaign advisor (the only character in the picture who’s not basically decent, and who therefore steals every scene he’s in).

The cast’s only weak link is Cameron Diaz as the cynical, cunning foster mom and system-gamer Miss Hannigan, a onetime wannabe R&B star. (The movie’s soundtrack has an urban contemporary coat of shellac, and there are pretty good new songs by compeer-producers Sia and Greg Kurstin.) Diaz is is a trouper who’s game for anything, and her big “Easy Street” number with Cannavale is enjoyable even though the director inexplicably hacks it to ribbons with unnecessary cross-cutting. But she lacks the exuberant crudeness and vampy joy that every other Hannigan has brought to the part. Diaz is not slinky enough or desperate enough, and she’s too wounded early on, which means we can’t be surprised when Hannigan reveals hidden, decent qualities.

This “Annie” won’t win any awards for subtlety, much less filmmaking elegance. But a great deal of imagination has been put into it, along with a lot of heart. This would be easier to see if the film were more of a self-regarding, art house showpiece, and less of a cotton candy multiplex confection—but what does it matter, really, when you’ve got Wallis deadpanning through a city of sugar? This “Annie” is so very, very welcome right now. Its easygoing, multicultural, can’t-we-all-just-get-along utopianism is a pop culture Band-Aid for a country with a bloodied sense of possibility. Judged purely on aesthetic merit, it is a two-and-a-half-star movie at best. The extra star is for sending people out of the theater wanting to hug and be hugged, then face whatever tomorrow may bring.