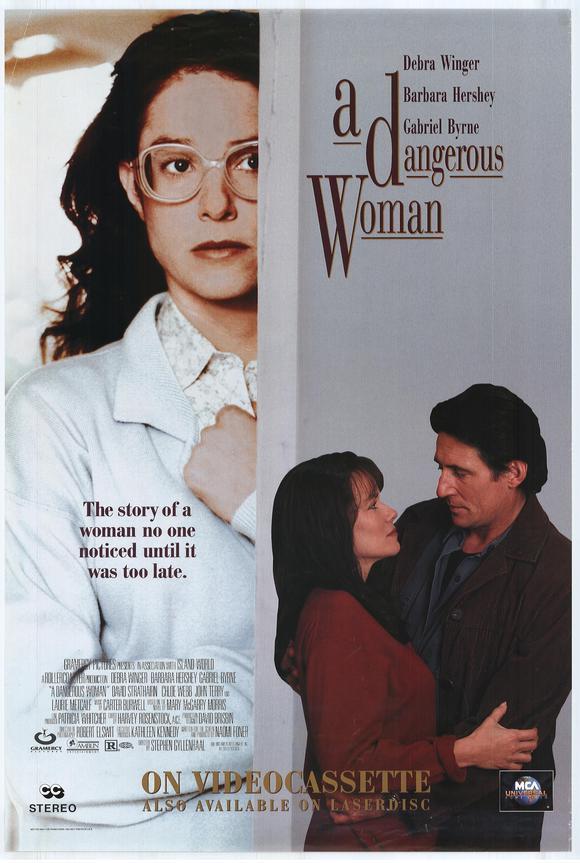

Observe the way Debra Winger plays her character in “A Dangerous Woman,” and you will learn something about the alchemy of acting. She doesn’t look particularly different in this film – aside, of course, from the details of makeup or hair style that help women express their beauty. You can always see that it’s Debra Winger. But she projects such a different essence in the film, so profoundly different, that you wonder how she’s doing it.

She plays a woman named Martha, who is slow, or somewhat retarded, or whatever word you want to use. She can function in the world, and even hold a job at the dry cleaners, but she is odd in her behavior, and children in the street feel safe to follow and mock her. Her home is the guest cottage next to the big house occupied by a close relative, Frances (Barbara Hershey), who has sort of inherited Martha as a responsibility.

Winger must have studied women like Martha in preparing for her performance. She must have lived beside them, observing a hundred different details. She puts them all together into a portrayal that never seems made up of those details, however; everything is of a piece, and after a time we are simply watching Martha, identifying with her. Look at the way Martha studies the movements in the faces of people she’s talking to. She all but peers at them, looking for clues, trying to read emotions and meanings. Look at the way she walks, filled with purpose, concerned with getting from here to there without false effort. Look at the way she stiffens when she is treated unfairly. Look at how proudly she insists that she always tells the truth.

The women live in a small town where everybody knows each other, more or less. Frances is a bit player in local politics, and it gradually becomes clear that she’s the victim of a series of affairs, that she tries to find herself through the assistance of men, and usually fails. As for Martha, she hardly seems aware there is such a thing as a sex life. Then one day an alcoholic handyman named Mackey (Gabriel Byrne) comes drifting into their lives, looking for work. It so happens that Frances’ frame porch has been caved in by an automobile driven by a jealous wife who thought, correctly, that her husband was inside the house. Frances sends the handyman away, but Mackey comes back anyway, and starts the job; he needs the work so badly he has no choice.

Eventually Mackey will become involved with both women. But it is not as simple as it might sound, because he isn’t bad – none of these people are bad – and in the loneliness and desperation of these lives many things can happen. His moral carelessness is fueled by alcoholism, which he acknowledges, although the movie in general doesn’t take it very seriously.

Mackey’s involvement sets a plot into motion, a plot that eventually involves another local man, Getso (David Strathairn) a worthless petty thief at the dry cleaners. Things happen. The movie is not really about the things that happen – it’s about the two women – but it’s as if the screenplay gets seized by a desire to tell the superficial story, and forgets to tell the real one. There is a pregnancy and a killing and a secret that cannot be shared, and it’s all really just melodrama.

I guess human stories have to be linked up to the mechanics of a plot in order to get financed, or to find an audience. No one would have wanted to see a movie that simply watched and listened with sympathy to the events in the daily life of a moderately retarded woman. But why is it that violence has to be involved? Why do so many plots depend on violence as the shortcut for creating dramatic tension. What do Martha and her job and her simple hopes have to do with all these distraught scenes in the police station, and all that blood? Look at another current movie, “Ruby in Paradise,” which by setting itself free from the contrivances of sensational plotting allows itself to be deep and true.

“A Dangerous Woman” raises more questions than it answers.

The handyman character is well-played by Byrne, and surprisingly sympathetic, considering he sometimes behaves in an unprincipled way.

But he functions too much as an invention of the plot, dropped into the story to busily make speeches and love. He doesn’t have much to do with the real lives of the two women. Then there is another character handled carelessly: the wife of Frances’ politician lover, who drove her car into the porch. This woman reappears in the movie at an important juncture and takes her husband back, and it’s all handled in long shots, without explanation, so that we can see she’s just a convenience for the screenwriter.

The movies are so seldom perfect that it’s enough to find something perfect in them. What’s nearly perfect in “A Dangerous Woman” is the Debra Winger performance. Her Martha seems to float above the inventions of the plot, in a world of her own. She may not know everything, but she knows what she knows, and acts on it to the best of her ability. She does not lie. She will not hurt another. She deserves her chance at happiness, and she knows it. It’s quite a performance.