Editor’s note: The first “Unloved” of 2015 is here and it is a timely, phenomenal piece about Michael Mann’s “Public Enemies,” a week before the release of his first film since the Johnny Depp drama, “Blackhat,” on January 16th, 2015. Scout makes the case that cinema had to catch up with the vision of the pioneer of digital photography in order for him to make a follow-up, and he does so with a precise examination of “Public Enemies.” As this video indicates, Mann’s rather prankish comfort with video-as-video (as opposed to video that’s going out of its way to mimic the texture and flicker of film) makes this movie a strange, at times unnerving experience. We’re not used to seeing 1930s period pieces that look like footage from the nightly news, complete with often-shaky handheld camerawork, blown-out bright spots, and slivery light trails. But it fits once you get used to the idea of “Public Enemies” as a movie that’s not about history per se, but about how the modern mind views history through movies—as well as the question of whether people really were somehow “different” in earlier times, and if so, in what way; and what, if anything, technology has to do with the change in self-perception.

Mann’s 2009 gangster drama retells the rivalry of gangster John Dillinger (Johnny Depp) and FBI agent Melvin Purvis (Christian Bale), with a side trip into Dillinger’s romance with Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard). It’s a tale we’ve heard many times before in movies and TV programs, fiction and history books, but as is so often the case with Mann, the film approaches the whole thing through eyes that are, in more than one sense, fresh. There are actually three love stories happening in the movie (more if you count the trademark Mann love affair between hard men and their jobs). Dillinger-Frechette is one. Purvis and Dillinger’s faintly Howard Hawks-like cat-and-mouse game might be another, considering it’s a cat-and-mouse rivalry based on one-upmanship and mutual respect in which two formidable individuals seem to be trying to both obliterate and awe each other. The third is Dillinger’s burgeoning love affair with his own image as fed back to him through newspaper and radio coverage and newsreels chronicling his bank robbing, Fed-taunting exploits. And it’s the third love story that lingers in the mind.

As written by Mann, Ronan Bennett and Ann Biderman (who created the excellent cop series “Southland”), “Public Enemies” is as much a consideration of fame and the construction of an alternate, “virtual” self as it is a dreamy, at times languorous cops-and-robbers picture wherein terse conversations and lovey-dovey interludes are periodically interrupted by beatings, car chases and deafening bursts of machine-gun fire. The structure apes Mann’s 1995 potboiler “Heat,” which divided its time nearly equally between a crew of thieves and the major crimes officers trying to ensnare them. It’s not as good at the basics, mainly because Purvis’s bloodless, micromanaging obsessiveness just can’t compete with Dillinger’s iceberg cool. Part of the problem is Bale’s acting, which consists mainly of variations on tight-sphinctered righteousness, but to be fair, he isn’t given much to work with. His Purvis might be the least fascinating lead male character in Mann’s entire filmography, and absent the sort of easily parodied yet undeniably hypnotic hamming that Al Pacino brought to a functionally similar role in “Heat” (“Cuz she’s got a greeeaaaaaat ass!”) there’s not much for a viewer to latch onto. One wonders if Mann realized this at some point during production; it might explain why Purvis recedes in the film’s second half, becoming a glorified supporting player. And it would explain why Texas Ranger Charles Winstead (played by Stephen Lang, one of the great utility infielders in film and TV) looms larger as the story unfolds, culminating in his face-to-face encounter with Frechette in a holding cell, the square-jawed cop doing his best to intimidate the little woman, failing miserably, and regarding her with genuine, earned respect.

Dramatic uncertainty on the law-enforcement side of the ledger lets Depp dominate the picture. He’s both perfect and perfectly cast. From his career-redefining work with Tim Burton in the ’90s, he’s always been a bit of a question mark as a leading man (like a handsomer Peter Sellers, maybe). Our sense of him as a private performer, closed off and often inscrutable, works brilliantly with Mann’s conception of Dillinger as a thief and killer who never entirely feels as though he’s a part of the world he travels through, and who regards the media-constructed image of Dillinger with curiosity, amusement, and occasional alarm. Like Bonnie and Clyde in Arthur Penn’s landmark 1967 drama, this Dillinger is part of the first wave of public figures transformed into entertainment via mass media. A big part of the film’s fascination comes from watching him toy with fame’s possibilities and wonder (silently, for the most part) what it means to be an icon as well as a person.

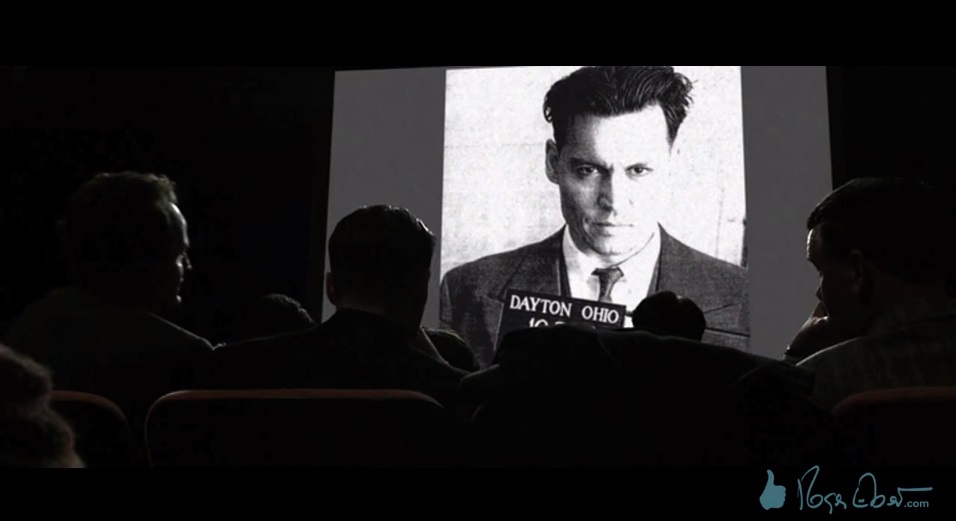

The film’s dramatic and conceptual high point isn’t an action scene, but a relatively quiet moment in which Dillinger sneaks into a police station and inspects an FBI organizational chart. Confronted by a black-and-white photo of himself as Public Enemy #1, he locks eyes with his still-framed reflection. In this complex moment, an autonomous man contemplates a second self envisioned by people he barely knows, and reckons with the troubling fact that they’re both him, and that the Dillinger in the papers and on the radio and on the silver screen is Dillinger, too. — Matt Zoller Seitz

(To read my 2009 review of the film for IFC’s web site, click here.)

Sequence 1-Public Enemies-Carax from Scout Tafoya on Vimeo.

To watch more of Scout Tafoya’s video essays from his series The Unloved, click here.