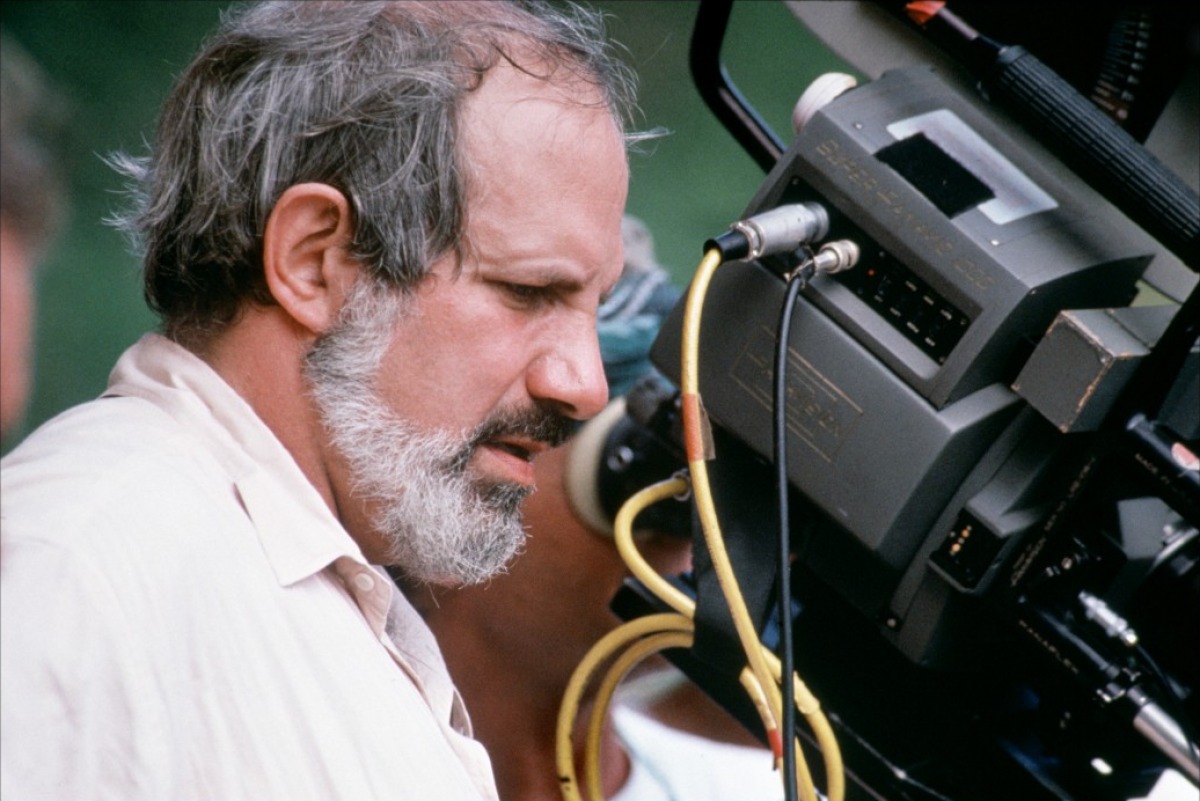

Veteran director Brian De Palma is the subject of the new documentary “De Palma,” a film by directors Jake Paltrow and Noah Baumbach that opens Friday. We spoke to him about his career in movies, the controversy over his depiction of violence and women, the question of whether TV is in the new cinema, and whether any great popular art has been made in the superhero movie genre.

Matt Zoller Seitz: What made you decide to participate in this documentary? I’m sure you get a million requests to do very long interviews.

Brian De Palma: Well, it didn’t start as a documentary. It sort of evolved because of the many dinners that [Baumbach and Paltrow and I] had together, talking about the kinds of things that directors talk about at dinner, in relationship to the movies they’ve made. And Noah and Jake were interested in a new digital camera, so they bought it, and they thought it might be interesting to record some of the stories I had told them over dinner.

So we went back to Jake’s apartment, and Jake operated the camera and Noah did the sound and they just basically asked me questions, recounting things that had had happened to me throughout my career.

I think they did a very good job illustrating what I was talking about. I did those interviews over five years ago, the footage sat around for a couple of years while [Jake and Noah] were making movies. And then they had some time to get back to illustrating what I was talking about, and did kind of a remarkable job. I don’t know if it’s good because I’m pretty honest about what happened to me, and I guess it’s very instructive to people getting involved in making movies, in Hollywood and elsewhere.

In the film, you talk a lot about the reception that different films of yours received, and also how well you thought they worked as movies, how good you thought they were. And two of the films that you seemed particularly proud of were “Casualties of War” and “Carlito’s Way.” I was heartened to hear that you think those movies are as good as many of your fans do, even though they weren’t necessarily your biggest hits.

Well, “Casualties of War” took, I don’t know, a decade to get made. I read the story in the ’60s and was later given the option to develop that turned around, and an option to develop that turned around. And it was only after the success of “The Untouchables” that I was finally able to get control of the property. It was the best story, it illustrated a tragedy in the Vietnam war, and I was very fortunate to have a very talented screenwriter, David Rabe, who also had been fascinated by this story that he had read in The New Yorker, as I had, 20 years earlier.

And I had a lot of power because I was coming off a huge hit, and we were able to put together this cast, and because Dawn Steel, who had left Paramount and gone over to Columbia, wanted a prestige movie, we were able to get a studio to finance it, and made a very good movie about the Vietnam War. Unfortunately, it was not well received, it was maybe too late. There had been many Vietnam movies, and it was a great personal tragedy for me, because I spent a long time trying to get it made.

And “Carlito’s Way” was again, treated like another Al Pacino gangster movie kind of business. But it was really a great script, based on two novels written by Edwin Torres. Again, at the time it came out, not much attention was paid to it, though I thought it was a very skillfully made movie from a very good script.

You talk a little bit in the documentary about the controversy that greeted some of your films—in particular, the idea that you like to put women in jeopardy. You talk about how it’s just more interesting for you to see women in jeopardy because they’re more physically vulnerable than men. I wonder if you think that some of your films that were criticized as sexist on those grounds, like “Dressed to Kill” or “Body Double,” could be made today, released today, with people being so much more sensitive to things like that?

Oh, I don’t know. They make a lot more violence in terms of torture porn, putting women in excruciatingly painful situations. I just was making those movies when women’s liberation movement was at its political peak, and they focused on violence in particular. It’s a kind of basic element of the genre, and just because the political atmosphere changes doesn’t make it any more valid.

I recently saw “Blow Out” again, on a big screen, at Roger Ebert’s Film Festival, and Nancy Allen was there, and I was struck by the John Lithgow character—not just how sadistic he was, but the really unsettling way that you portray him. He really gets off on terrorizing women. The movie doesn’t, though; the movie is appalled by him, I think. You have a lot of men in your movies who are macho, who are very macho, who are very often military, or they’re cops, or they’re a hyper-masculine sort of role model, and you seem really, really disgusted by their conditioning, by their behavior. Is part of your movies kind of a critique of the sorts of masculinity that other movies celebrate?

I don’t know. I don’t know if you can make a sweeping statement about these types of characters. John Lithgow’s character was very much based on G. Gordon Liddy. That was a very specific reference point, and I don’t think I ever had something quite like that again in a movie.

But in “Casualties of War” and some of the characters in “Carlito’s Way” and certainly in “Scarface” you see a kind of a ridiculousness to machismo.

They’re gangster movies; they’re war movies! Movies like that tend to be very masculine.

But you don’t glamorize them, even though you sometimes find them funny or horrible. I was just curious about that, because I have read a lot about your work and have seen a lot of critiques of the kinds of stories you tell, and that’s one aspect I’ve always wondered about: your attitude about machismo, which feels like it’s related to the way men terrorize women. You seem like somebody who is maybe not a political filmmaker in a way that some filmmakers are, but I wonder, could there be a political aspect to the way that you portray men and women?

It all came from the genre! You know? I don’t think there’s any through line, basically. I’m basically interpreting the material.

The movie opens with Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” and returns to Hitchcock, many, many times throughout its run. You talk about yourself as a filmmaker who speaks in Hitchcock’s vocabulary, and you seem to wonder why more people don’t.

It seems quite obvious to me, but I studied Hitchcock’s movies and some of his techniques and vocabulary because they’re so cinematic! He had some excellent ideas, whether it be with “Rear Window,” of a guy watching somebody across the yard in the apartment, or the crop duster in “North by Northwest.” These are stunningly visual ideas. These types of things excited him because they’re so cinematic. And a lot of that is sort of banished is present day filmmaking, because a lot of stuff is driven by dialogue scenes, and the screens have gotten smaller. This kind of visual storytelling has kind of gone out of style.

Do you think that it’s harder for people like you, of your generation or your sensibility, to get well-budgeted personal films made in the system, than it was when you were starting out, or even than it was five years ago?

Well, it depends on what film you’re going to make. If it just requires a couple of people in live locations, and you don’t require too many elaborate visual sequences, sure, it’s a lot easier to make movies like that now, because you need [a lot of] equipment, and what you’re shooting on is so inexpensive. But it might be harder if you’re going to make elaborate visual sequences, and you need all that stuff that larger budget movies give you.

Have you thought of going to television? Does that interest you?

No. I worked on a project once for HBO but it didn’t work out.

There have been people in the industry who have made rather extravagant claims for television, and said things like “television is the new cinema.” What do you think about that?

Television is not cinematic. It’s shots of people talking to each other.

Is it possible that the kind of language you define as cinematic could exist on a smaller screen, though? Has it ever?

It would be difficult, because television is basically controlled by the producers and the writers. The directors are brought in to a series or a ten-part story, and the template has already been set. It’s shot very quickly, and you don’t have the time for sort of elaborate sequences, you can only shoot so many pages a day, the characters are all set, the story lines are all plotted out for the next four or five years, it’s like the old studio system.

Is there a movie of yours that you feel has still not gotten its due, that has still not been discovered or appreciated in a way that you would like?

Well, it’s hard to say. The way they land, where you see them after they have been initially been, really—a lot of my movies appear in retrospectives and on television. So: which ones appear over and over again? It’s “The Untouchables” that seems to be playing all of the time somewhere. That’s basing the power on being seen a lot, and enough movies seem to be confidently being viewed in one form or another.

It almost sounds like you’re saying the audience makes its choice, and you’re OK with it?

A movie is a work of art. It either exists and people keep looking at it, or it vanishes. So, I have very little to do with it, and a movie has basically got to find its own way. And many of my movies, people are still looking at 30 or 40 years later, so I guess there’s some value in it, because they’ve existed through the ages.

Do you still feel like a low-budget filmmaker sometimes? You’ve made some very big productions but the way you talk about them, I don’t necessarily see money playing a whole lot of role into the difficulties you face creatively.

Well, the bigger the budgets, the more meetings you have. And if you have a very small budget you have a lot of control, and you don’t have any meetings. So, it depends on the material and what you need in order to make the story effective.

Are you actively working on a movie now, or more than one movie?

I am developing material, and you get to an experience where you’ve done the script and it’s in pretty good shape, and you go out and try to get a cast and then you try to get it financed.

What was the first scene that you directed where you were 100% happy with every aspect of it?

I don’t think you evaluate your work that way. You try to do the best you can under the circumstances it’s intended with. And if you’re fortunate, and if everything is clicking that day, you might come up with something remarkable. I can’t think of many instances where I left the playing field and not accomplishing what I set out to do.

Do you think that there’s anybody out there working in the suspense or thriller vein whose work is really top-notch? Somebody who is new, who has come along in the last five or ten years?

Nothing springs to mind.

Do you go to the movies a lot?

I go to film festivals and see movies, and I watch a lot of stuff on TCM, and I’m exploring an actor that I might think might be right for something I’m working on, I go and look at all their movies.

Do you write for particular actors?

Well, when I was doing for “Dressed to Kill” and “Blow Out,” I wrote those girl parts for Nancy. And when I did “Sisters” I wrote the parts for Margot [Kidder] and Jennifer [Salt].

What do you think is the most useful advice you can give an actor who wants to act for the camera, to be a movie actor as opposed to a stage actor?

It’s very difficult, because actors are all trained very differently. And it’s difficult to get a handle on what exactly works on film. A lot of the times, because so much of film is a cult of personality, I don’t think anybody had to give Steve McQueen any acting concepts, he was just a presence. And a lot of that works in cinema, when you crowd material around a certain movie star.

But you have to be very patient and loving with your actors, because they’re putting everything on the line, and you have to try to get everything out of the way to not hurt their performances or distract them.

Your films are often remarked upon as examples of extraordinary control over image and sound, but throughout this documentary you also talk about the things that are not in your control: when a movie is shot, how much of a budget you get or don’t get, things that go wrong, actors that maybe you’re stuck with even if you know that they’re not quite right for the part. Do you think there’s some truth to this idea that part of what a director does is preside over accidents? Or at least manage things that aren’t in their control?

Well you have to be incredibly prepared, because you have to have a plan when you go to shoot. But things happen: the weather, how the actor feels, what somebody ate the night before. You have to be aware and you have to be able to improvise, depending on what is happening in the moment.

There’s nothing like preparation for dealing with situations like that, so that you can shift from one thing to another painlessly.

Can you give me an example from your movies of something not going to plan, that satisfied you? Where you didn’t get to do what you wanted to do, but you still liked the result?

For “The Fury,” there was a very complicated panning shot that Carrie [Snodgrass] didn’t want to do, because she had to hit certain marks for it to work. She just couldn’t get her head around why she had to be at a certain place at a certain time, because it didn’t seem natural to her. So I had to sort of carefully adjust the shot to something that she understood in order to make it work, so that what I wanted to do and what she wanted to do was in harmony. And it all worked out fine. And she didn’t quite understand it until she saw the rushes.

The great disadvantage of directors of my generation, as opposed to directors working in the studio system, is that you don’t get to direct as many movies as they did. They were under contract, they were directing 52 weeks out of the year. So we think about what we’re doing and maybe get our chance out and do it once a year, if we’re lucky. Sometimes many years pass before you are directing [again]. You can learn a tremendous amount by just practicing your craft. And obviously the great directors of the generations before, either Hitchcock, Ford or Hawks, directed a tremendous number of pictures, nowhere near the number that we’ll ever get a chance to do.

Are there moments in which you wish you were directing in the 1930s or 40s, where you’d have that opportunity you describe, to direct three of four films a year, under contract?

I don’t know. It was a different time and a different system. I’m sure there are directors that are doing hour-long television series that are directing all of the time, too. And the directors of the television generation that came before I did, who did a lot of television, had a lot of experience in directing live television shows, like Sidney Lumet. So, it’s hard for me to say.

I just know that you should practice your craft as much as possible, and not just be sitting around waiting for the time when you get the cast and the money together, so you can go out and make the film you’ve been thinking about for three or four years.

Is there anything that you think can be done to make film more hospitable right now, to artists or people who have an idiosyncratic sensibility, so that they could make more movies?

Well, there are a tremendous number of movies being made, but at a certain budget which limits them. And there’s a tremendous amount of television being made. Big movies that require a lot of digital design are basically comic book movies now. Or they have the kind of budget that you need to carry out these incredible suspense sequences, like in “Mission: Impossible,” stuff like that.

Have there been any movies made in the superhero genre recently that you thought were artistically interesting?

I was never interested in comic books. This whole sequel-and-comic-book era of movies doesn’t really interest me much. But, you know, I’m in my 70s, why should it?