Charles Bronson is said to be the world’s most popular movie star. Not America’s. He will grant you Robert Redford in America. But in the world it is Charles Bronson. There is a sign in Japan, his publicist says, that displays Bronson’s name a block long (one does not ask how high).

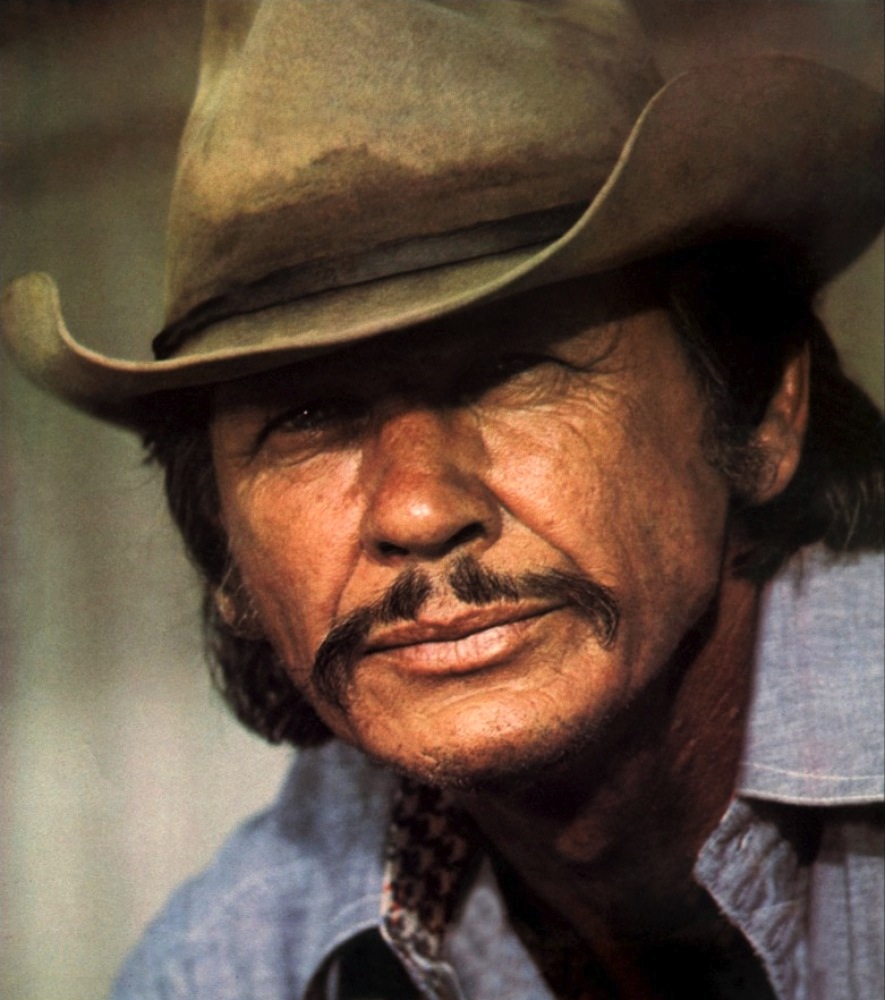

Bronson’s eyes are a cat’s eyes, watchful and guarded. They are the eyes of a man of fifty-one who once was a coal-town juvenile delinquent, spoke broken English, and embraced the draft in 1943 as away to escape from the mines. These eyes were watching me one afternoon from across the dining room of the Capri Motel in La Junta, Colorado. They pretended not to, but they did. Their owner knew that I was in La Junta to interview him. What other mission would have drawn me to the cantaloupe capital of Colorado, where Bronson was shooting “Mr. Majestyk,” a movie about a melon farmer with union troubles? He had no great eagerness to be interviewed. He seemed to be sizing me up, with a sort of survivor’s instinct.

It is conventional to say of movie stars that they are very private people, but Bronson has contructed a privacy so complete that it seems out of keeping with his occupation as a performer. He exudes an aura of privacy; I did not feel like approaching him. He sat at the head of a table with his wife of six years, Jill Ireland, at his left hand. Their children ranged around them: three by Jill’s previous marriage to David McCallum, two from Bronson’s first marriage, and their daughter, a perfect little blonde born in 1971.

Bronson finally sighed and handed his daughter to his wife. He came to be interviewed, after all. He does not mean to be difficult, but it is in his nature. He does not volunteer information, does not elaborate, and has no theories about his films (“I’m only a product like a cake of soap, to be sold as well as possible”).

To make everything harder, Time magazine had printed a hostile review only that week of Bronson’s latest movie, “The Stone Killer.” The writer, Jay Cocks, dismissed it as another “Charles Bronson-Michael Winner picture.” To Bronson, that was a personal attack. “First it was a novel, then it was a screenplay, and there was a cinematographer involved and a lot of other people. That makes it personal, when he picks on just two people, and that gets me mad.” An ominous pause “One way or another,” he said, “sooner or later, l’ll get that man. Not physically, but I’ll get him.”

There is that about Charles Bronson, and it is unsettling. He really does seem to possess the capacity for violence. It is there in his eyes, and in his muscular forearms, and in the way he walks. Other actors can seem violent in their roles; Lee Marvin, certainly, and Robert Mitchum and Clint Eastwood. But they don’t seem violent in person. Bronson does. Maybe that’s because he has been there, and violence isn’t strange to him: back when he was Charles Buchinsky from the coalfields of Ehrenfeld, Pennsylvania, he did time twice, once for assault and battery and once for robbing a store. There were hard times early on in Ehrenfeld, and in the Air Corps, and working in mob gambling joints in Atlantic City. Director Michael Winner once told me: “After we’ve been on a picture a few weeks, the crew starts coming around and asking, When does it happen? When does he blow up? Actually I’ve never seen him blow up. But he seems to contain such a capacity for it that people tend to brace for it.”

The breath of menace blows over as Time is forgotten, and in a moment Bronson is talking about his favorite pastime, which is painting. “When I was a kid,” he says, “I was always drawing things. I’d get butcher paper or grocery bags and draw on them. And at school I was the one who got to draw on the windows with soap. Turkeys for Thanksgiving, that kind of thing. It seemed I just knew how to draw I could draw anything in one continuous line without lifting the crayon from the paper. I had a show of my stuff in Beverly Hills and it sold out in two weeks – and it wasn’t because my name was Charles Bronson, because I signed them Buchinsky.”

He will talk about his painting, but not about his acting. In action pictures like Winner’s, he says there’s not that much time for acting. “I supply a presence. There are never any long dialogue scenes to establish a character. He has to be completely established at the beginning of the movie, and ready to work. Now on this picture, ‘Mr. Majestyk,’ there’s something I haven’t done for a while — acting. It has that, too, besides the action.”

This sounds like modesty, but one senses it is not; it is just Bronson’s description of what he does. He seems to consider himself a professional who can get the job done without investing a lot of ego in it. And apart from his pride of craft, the job is important not because it produces great movies but because it permits him to provide an extraordinarily comfortable life for his family.

He points out that as the eleventh of fifteen children of an illiterate coal miner who died when Bronson was ten, as a coal miner himself between the ages of sixteen and twenty, and as mailman, baker and onion picker at various other times, he has had great good fortune to arrive at his current condition: He is allegedly the highest-paid movie actor in the world. That is a claim more than one actor is usually making at any given time, and so later I put the question point-blank to producer Walter Mirisch, who was paying him. Is he?

“Some of the other guys might make more per picture,” Mirisch said, “but Charles makes more pictures. And they never lose money.” How much does Charlie make? I asked “On this picture,” Mirisch, sounding like the afternoon market report from Hornblower and Weeks-Hemphill, Noyes, “Charlie is making twenty thousand dollars a day for a six-day week, plus ten percent of the net, plus twenty-five hundred a week walking-around money. On his next picture, he’ll probably make more.”

I saw Bronson again several months later in New York, where he was working once more with Winner (who also directed him in “Chato’s Land,” “The Stone Killer,” and “The Mechanic”). The new movie was “Death Wish,” about a middle-aged New York architect who is repelled by violence until his own daughter is raped and his wife murdered. Then the architect becomes an instrument of vengeance. He goes out into the streets posing as an easy mark, and when muggers attack, he kills them.

“Death Wish” was being shot in New York in late, cold February, and for openers I observed that the character seemed to have the same philosophy that’s been present in all of Bronson’s work with Winner: He is a killer (licensed or not) with great sense of self, pride in his work, and few words.

Bronson had nothing to say about that “I never talk about the philosophy of a picture,” he said. “Winner is an intelligent man, and I like him. But I don’t ever talk to him about the philosophy of a picture. It has never come up. And I wouldn’t talk about it to you. I don’t expound. I don’t like to overtalk a thing.”

We are in the dining room of a Riverside Drive apartment that is supposed to be the architect’s home in the movie. Bronson is drinking one of the two or three dozen cups of coffee he will have during the day and, having rejected philosophy, seems content to remain quiet.

Could it be, I say, that it’s harder to play a role if you talk it out beforehand?

“I’m not talking in terms of playing a role,” Bronson said. “I’m talking in terms of conversation. It has nothing to do with a role at all. It’s just that I don’t like to talk very much.”

He lit a cigarette, kept it in his mouth, exhaled through his nose, and squinted his eyes against the smoke. Another silence fell. All conversation with Bronson has a tendency to stop. His natural state of conversation is silence.

Why?

“Because I’m entertained more by my own thoughts than by the thoughts of others. I don’t mind answering questions. But in an exchange of conversation, I wind up being a pair of ears.”

On the set, I learned, he doesn’t pal around. He stays apart. Occasionally he will talk with Winner, or with a friend like his makeup man, Phil Rhodes. Rarely to anyone else. Arthur Ornitz, the cinematographer, says. “He’s remote. He’s a professional, he’s here all the time, well prepared. But he sits over in a corner and never talks to anybody. Usually I’ll kid around with a guy, have a few drinks. I think there’s a little timidity there. He’s a coal miner.”

Later in the day, Bronson is sitting alone again. I don’t know whether to approach him; he seems absorbed by his own thoughts, but after a time he yields. “you can talk to me now. I wouldn’t be sitting here if I didn’t want to talk. I’d be somewhere else.”

I was wondering about that.

“I had a very bad experience on the plane in from California yesterday. There was a man on the plane, sitting across from me, and they were showing an old Greer Garson movie. He said, Hey, why aren’t you in that? The picture was made before I even became an actor. I said, Why aren’t you? I think I made him understand how stupid his question was.

“When I’m in public, I even try to hide. I keep as quiet as possible so that I’m not noticed. Not that I hide behind doorways or anything ridiculous like that, but I hide by not making waves. I also try to make myself seem as unapproachable as possible.”

More silence. Phil Rhodes, the make-up man, is leafing through a copy of Cosmopolitan. Suddenly he whoops and holds up a centerfold of Jim Brown.

“Will you look at this,” he says.

“Would you ever do anything like that, Charlie?”

“Are you kidding?” Bronson said. “What a bunch of crap. Look at that. Old Jim. People are so hung up on sex.”

And, inexplicably, that sets Bronson talking “I’ve been trying to make it with girls for as long as I can remember,” he says. “I remember my first time. I was five and a half years old, and she was six. This was in 1928 or 1929. It happened at about the worst time in my life. We had been thrown out of our house . . .”

The house was in Ehrenfeld, known as Scooptown, and it was a company house owned by the Pennsylvania Coal and Coke Company. When the miners went out on strike, they were evicted from their homes, and the Buchinsky family went to live in the basement of a house occupied by another miner and his eight children. “This would have been the summer before I started school,” Bronson says. “I remember my father had shaved us all bald to avoid lice. Times were poor. I wore hand-me-downs. And because the kids just older than me in the family were girls, sometimes I had to wear my sisters’ hand-me-downs. I remember going to school in a dress. And my socks, when I got home sometimes I’d have to take them off and give them to my brother to wear into the mines.

“But, anyway, this was a Fourth of July picnic, and there was this girl, six years old. I gave her some strawberry pop. I gave her the pop because I didn’t want it; I had taken up chewing tobacco and I liked that better. I didn’t start smoking until I was nine. But I gave her the pop, and then we . . . hell, I never lost my virginity. I never had any virginity.”

He remembers Ehrenfeld well, and has written a screenplay with his wife about life in the mining towns. He worked in the mines from 1939 to 1943, and getting drafted, he says, was the luckiest thing that ever happened to him: “I was well fed, I was well dressed for the first time in my life, and I was able to improve my English. In Ehrenfeld, we were all jammed together. All the fathers were foreign-born. Welsh, Irish, Polish, Sicilian. I was Lithuanian and Russian. We were so jammed together we picked up each other’s accents. And we spoke some broken English. When I got into the service, people used to think I was from a foreign country.”

Five boys in his family were drafted into the Army. An older brother, the one who took him into the mines for the first time, was part of the European invasion. “He was a Ranger, and he won a medal,” Bronson said. “He was under fire constantly. And he said he’d rather do that than go into the mines again.”

Bronson would not talk about his hometown screenplay, called $1.98, except to say it was fundamentally a love story with a mining town as the environment, but the next afternoon he met with two VISTA workers to discuss possible locations in Appalachia for the film. The towns he had scouted, he told them, looked too good. There were streets, there were lawns where things grew . . .

“I remember the old company towns. There was no neon, except for the company store. Nothing was green. The water was full of sulphur. There was nothing to put a hose to. There were unpaved streets covered with rock and slag. You had the rock dumps always exploding. They were always on fire, down inside, and if it rained for a long enough time, the water would seep down to the fires and turn to steam and the dump would explode.”

The VISTA volunteers asked if Bronson’s movie would deal with black lung disease.

“No, it’s a love story. But it will be . . . beneficial to the miners, I hope. Right now it isn’t a finished script. There are too many empty, dull places. And it’s naive. But it will be accurate about mining. You had a feeling about mining. It was piecework; you didn’t get paid by the hour, you got paid by the ton, and you felt you were the hardest-working people in the world.

“When I worked, the rate was a dollar a ton. You spent one whole day preparing so you could spend the next day getting it out. The miners felt bound together; they knew how much they could get out, how much they could do. And they worked. With the new machines, it’s easier. Not more pleasant, but easier. But in those days, that was pure work. It wasn’t a man on a dock with a forklift or any of that bullshit. It was pure work.”

After the war Bronson went back home, but not to the mines. The veterans were given three months, he recalled, to decide if they wanted their old jobs back. Bronson did not. He picked onions in upstate New York, and then got his card in the bakers union. He worked on an all-night shift at a bakery in Philadelphia and took art classes in the evenings. He decided he knew more about drawing than the instructor did. He dropped the classes and quit his job (he still holds cards in both the miners and bakers unions), and went to New York City with the notion that he might try acting. Why acting?

“It seemed like an easy way to make money. A friend took me to a play, and I thought I might as well try it myself. I had nothing to lose. I hung around New York and did a little stock-company stuff I wasn’t really sure at that time if l even wanted to be an actor. I got no encouragement. I was living in my own mind, generating my own adrenaline. Nobody took any notice of me. I was in plays I don’t even remember. Nobody remembers. I was in something by Moliere — I don’t even know what it was called.

“I have no interest in the stage anymore. From an audience point of view, it’s old-fashioned. The position I’ve been in for the last eight years, I have to think that way. I can’t think of theater acting for one segment of the population in just one city. That’s an inefficient way of reaching people.”

After New York, he tried the Coast. Spent some time at the Pasadena Playhouse. Got his first movie role in You’re in the Navy Now because he could belch on cue, a skill picked up during Ehrenfeld days. He worked for years as the heavy, the Indian, the Russian spy. He had two TV series, “Man with a Camera” and “Meet McGraw.” And he was getting nowhere fast, he decided, so he went to work in Europe, where they didn’t typecast so much and he had some chance of playing a lead or getting the girl.

His first great European success was in Farewell, Friends, opposite Alain Delon. That made him a lead, and then movies like “The Dirty Dozen” and “Rider on the Rain” made him a star. Although he worked for years in Europe, he refused to live there; he always maintained his home in America. He met Jill Ireland on a set in Germany in 1968, three years after her separation from McCallum and a year after her divorce. And now, he says, “I don’t have any friends, and I don’t want any friends. My children are my friends.”

And in Europe, Asia and the Middle East, he is said to be the top box-office draw. “One of the ironies,” he observed, “is that I made my breakthrough in movies shot in Europe that the Japanese thought were American movies and that the Americans thought were foreign.”

That night in New York, the Death Wish company gathered to shoot a scene outside a grocery store on upper Broadway. Bronson said that, since he was here anyway, he would do some shopping. He began with a box of cookies. An old man, a New York crazy, was berating a box of Hershey bars because it wouldn’t open. What the hell’s going on here? he shouted at the box. Bronson opened it for him. The man hardly noticed.

While the location was being prepared, Michael Winner drank coffee across the street and talked about his enigmatic star.

“It’s unnecessary for him to go into any big thing about what he does or how he does it,” Winner said, “because he has this quality that the motion-picture camera seems to respond to. He has a great strength on the screen, even when he’s standing still or in a completely passive role. There is a depth, a mystery — there is always the sense that something will happen.

I mentioned a scene in “The Stone Killer” in which Bronson has a gunman trapped behind a door. The gunman fires through the door, and Bronson, with astonishingly casual agility, leaps to the top of a table to get out of the line of fire.

“Yes,” said Winner. “His body projects the impression that it’s coiled up inside. That he’s ready for action and capable of it. You know, Bronson is, as a human being, like that. That’s not to say he goes about killing people. I’m sure that he doesn’t”

A pause. “That’s not to say he hasn’t, in his day. Now he seems to have gotten a reputation for blowing up and hitting people on pictures. In my experience, he’s not like that. He’s a very controlled and reasonable person.” Pause. “But there is a great fury lurking below.”

The next afternoon, Bronson taped an interview for exhibitors with some people from the publicity department at Paramount. Bronson described the character he plays in “Death Wish”: “He’s an average guy, an average New Yorker. In wartime, he would be a conscientious objector. His whole approach to life is gentle, and he has raised his daughter that way. Now he has second thoughts, and he becomes a killer.”

Did you prepare for this character in any special way?

“No, because to play him I draw upon my own feelings. I do believe I could perform this way myself.”