Check back for Roger Ebert’s dispatches from the 58th Festival de Cannes, May 11 – 22, 2005.

The official Cannes Film Festival web site is here.

Roger Ebert has been attending the Cannes Film Festival, the most celebrated and glamorous such event on our planet, since 1972. On the occasion of the festival’s 40th anniversary, Ebert published a book of Cannes memoirs, Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook (Andrews and McMeel, 1987), which we have reprinted, in part, here. Packed with festival folklore — humorous anecdotes and legendary characters that invariably swirl around the world’s glitziest and most famous film festival — Ebert offers you his own personal tour of Circus Cannes, explaining bizarre rituals and colorful local customs, and capturing the frenzied, star-struck, jet-lagged atmosphere of the Scene (and Be Seen) By the Sea. You’ve never “seen” Cannes quite like this — recounted as only Ebert, an observant critic and reporter who has shared such a rich history with the festival, possibly could. Bon appetit! (And be sure to check out Roger Ebert’s own pictures from past festivals in the photo gallery.)

Ritual “jet lag”

I always awaken very early on my first morning in Cannes, just at dawn, and pull on my jeans and a sweater to walk down by the old port for a cup of coffee at the all-night cafe. The street-cleaners are washing away the debris of the night before with fire hoses, and sometimes they will direct a spray into the air so that it catches the rising sun and creates a rainbow. I am always very tired when I choose my table on the sidewalk—it must be the same table I have taken for the past 12 years—but I am happy. I tell myself it is jet lag that makes me rise so early, but in fact it is ritual. I must sit just precisely here, across from the park with the stubby sawed-off city trees that look so desperate and forlorn, and compose myself for the ordeal ahead.

It sounds like great fun to cover the Cannes Film Festival. It is one of those events, like the Super Bowl, Wimbledon, or the Kentucky Derby, that comes cloaked in its own legend. But if the Super Bowl were two weeks long, that would be more like Cannes. I have in my hand the first issue of Screen International, fresh from the presses, the daily English-language newspaper of Cannes, and it is 158 pages long. Most of the pages are given over to ads for movies that will be shown here, in and out of the competition, and as I riffle through them my annual case of gnawing insecurity begins to form. I will not be able to see more than a fraction of these films. I will miss some of the good ones. I will waste my time at the bad ones. I will never be able to find all of the stars and all of the directors I should interview, and if I do succeed, say, in tracking down someone really interesting like Barbara Hershey or Dusan Makavejev, my editors will want to know why I didn’t have lunch with Elizabeth Taylor.

For the next two weeks, I will be covering a story with no end and no shape. Every morning at 8:30 there will be the first of the day’s press screenings, and every night at midnight another party will be just beginning. My job will be to think in two ways at once: To be a critic, evaluating the film I see and trying to find some sort of pattern in them, and to be a gossipmonger, trying to discover the real reason why Bo Derek has made only two films since “10” (1979). The only constant will be my battle with my computer. The people will drift in and out of focus, on the screen and at lunch and dinner and poolside at the Majestic and on the Carlton Beach and out at the Hôtel du Cap d’Antibes and on the sidewalks and in the cafes, and it will all be disconnected, and I will convert it all somehow into copy that will make the Cannes Film Festival sound like a jolly round of glamorous interviews.

If I am lucky, however, something extraordinary will happen to me during this festival. I will see a film that will make my spine tingle with its greatness, and I will leave the theater speechless. There is no better place on earth to see a movie than in the Palais des Festivals at Cannes, with its screen three times the size of an ordinary theater screen, and its perfect sound system, and especially its audiences of 4,000 people who care passionately about film.

Anyone who goes to Cannes in search of masterpieces will, however, be frequently disappointed. There are Dantean levels to this festival. At the top level is the Official Selection, the films chosen from all over the world by Gilles Jacob, the director general, and Pierre Viot, the president of the festival. Then there are the lesser levels, the sidebar events, the marketplace screenings, all the way down to the fire sales of forgotten videos. The morning press screenings of the Official Selections are followed by chaotic press conferences, the stars and directors assaulted by television lights, paparazzi, and idiotic questions (“I just want to know, is Mr. Newman free for lunch?”). The evening premieres, where formal wear is required, are a spectacle of sound and light. While loudspeakers endlessly blare, “Thus Spake Zarathustra,” thousands of movie fans crush up against police barricades while the filmmakers and the stars alight from limousines and walk a city block to the vast flight of outdoor stairs leading up to the Palais. They stop on the first landing, turn, wave, climb up to the second landing and wave again, into thousands of flashbulbs.

It would be easy to bring the stars in by a back entrance, but alien to the whole idea of the festival. At the old Palais, down at the other end of the Croisette, the nightly processions up the stairs became a world-famous ritual, and when they designed the new Palais they made the stairs wider and taller. Indeed, they also made them too steep, and in the first season of the new Palais, there was the danger that a photographer would trip and fall, starting a human tidal wave to tumble down and crush the stars below. So they rebuilt the stairs to reduce the angle, but they still required the stars to run an obstacle course, arriving in limousines, walking down the red carpet, climbing the stairs, all in full view of the thousands of fans who have arrived, some of them, from all over Europe because they know they will be given a fair chance to see their heroes in the flesh. Many movie stars have not appeared on the stage for years, and, although their fame is vast, they may never have received a great ovation; their arrival at Cannes is the nearest they may ever get to scoring a winning touchdown. Some of the French stars seem addicted to the ritual, and attend every year; Gerard Depardieu is such a familiar sight, cruising the Croisette on his motorcycle, that he’s one of the institutions of Cannes, like Edy Williams, that you expect to see.

Sometimes the crowd scenes turn ugly. When the star is someone of truly great magnitude—Catherine Deneuve, say, or Clint Eastwood—the crowds spill out over the plaza and into the street and the trees are filled with photographers, and there is always the possibility that things will get out of hand. The air is charged. The night that James Stewart came to Cannes, in 1985, the mob was so enthusiastic that the old man got jostled about inside his cordon of policemen, while the loudspeakers played “Tuxedo Junction.” There is always the possibility of a riot whenever Jerry Lewis comes to Cannes, and when he was here in 1983 with Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy” he told me how he works the crowds: “You have to always walk slow. What they want is a good look at you. If you walk fast, they’re afraid they won’t see, so they run to keep up, and mob psychology snowballs, and there’s a riot. In a crowd, I always walk nice … and … slow. Hello! Here I am! Hi there! Look how slow I’m walking! Hi there, buddy! How are you?”

Levels of the inferno

The grand entrances at the Palais des Festivals are mirrored, in a grubbier and more informal way, down at the older festival palace, which was built right after the war. The Palais Croisette, as it is now called, has been threatened with demolition to make way for another of the squat luxury hotels which line the beach, but so far it has been spared as the home of the Quinzaine, an event inspired by the riots of 1968, when radical filmmakers shut down the festival on grounds that it represented reactionary establishment tastes. Now the Director’s Fortnight is programmed with smaller films from around the world, and it has been a sendoff for the careers of several American directors recently: Susan Seidelman came here with “Smithereens,” and Spike Lee with “She’s Gotta Have It,” and Jim Jarmusch with “Stranger Than Paradise,” and their success here helped get their films launched in the U.S. When the directors arrive for the Director’s Fortnight, there is a repeat of the mob scene at the new Palais, with the difference that the crowds look like street people instead of bourgeois fans, and the directors are likely to be wearing T-shirts instead of tuxedos.

On successively lower levels of the Cannes inferno, after the official selections and the Quinzaine, there is Un Certain Regard, a category for films the festival has “a certain regard” for—and only in France would that be considered a compliment. Somewhere below that is the Marché du Film, the marketplace, where movies are bought and sold after being screened from morning to midnight in the little commercial theaters that line the rue d’Antibes. And then, down at the very bottommost level, there are the nameless videos that are retailed from small booths in the basement of the Palais, where I met a man named Ken Hartford, who cheerfully explained that he sold movies by the pound.

The marketplace is often the scene of some of the festival’s greatest vitality. Here the movies have no pretensions of artistic greatness; they promise only to sell tickets. Three years ago in the marketplace, I came up on Stuart Gordon’s “Re-Animator,” a horror film inspired by Lovecraft and filled with images so strong and shameless that the movie took on a crazy, inspired dementia. A year before that, there was Mark Lester’s “Class of 1984,” a high-school horror movie that, to borrow an expression from Mel Brooks, rose below vulgarity. Until five or six years ago, the marketplace also featured a lot of porno films, but that market has disappeared because of home video. Now the stars of the marketplace are likely to be titles and ad campaigns, which for a certain kind of product are more important than the movie itself.

Most press conferences at Cannes are worth missing, which you cannot easily do, since they are carried by closed-circuit television to every hotel lobby and public area. The routine is always the same. The director and the actors file onstage, followed by various assistants, costars, translators, and flunkies. Dozens of cameramen instantly stand on their chairs and begin to shoot photographs. The writing press immediately sets up a chant: Asseyez vous! Asseyez vous! Down in front! A festival spokesman makes dire warnings that the photographers will be ejected if they do not comply. The star of the press conference lights a cigarette or pours a glass of water. Then it is time for the questions, which come in several languages and usually include at least one political speech, one job application, one attempt at shameless flattery of the subject, and one completely insane remark that no one can understand. It is traditional for the subjects of the press conference to appear bored, and slightly irritated, as if they are not sure why they must subject themselves to this bombardment. These doubts have occurred to them, of course, after they have spent thousands of dollars and flown thousands of miles in order to be here.

Some answers are absolutely standard. No matter who is being interviewed, you can be sure that (1) everyone sharing the dais with the speaker is an absolutely marvelous and talented human being; (2) the film has been a pet project for years; (3) it doesn’t matter if it wins a prize, because being here at Cannes is honor enough; (4) nobody has the slightest idea what the message of the film is, or indeed if it has one; (5) all interpretations of the film by the journalists are quite plausible; and (6) it is just a shame the filming had to end, and everybody is looking forward to working together again as soon as possible.

The Palais was guarded by thin-lipped security experts, who are veterans of the annual tradition of bomb threats, and by ushers in matching uniforms, whose duty is to lock the doors to a screening until a riot is threatened, and then open them briefly so that hundreds or thousands of people can try to crush through them. This seems like a dangerous and illogical system of crowd control, but actually it is inspired by the French national attitude toward queues—which is that they are intended for chumps, preferably English-speaking ones.

The Americans and British at Cannes dutifully stand in line for everything, and the French habitually walk right past the line and in through the door. If you protest, you get the sort of blank look they reserve for the lower orders. They seem to think that anyone stupid enough to stand in line deserves to be made to wait.

Over the years, this has become a personal issue with me. I become hyperalert to anyone who is trying to push ahead of me, and on occasion make loud protests. But the French simply do not understand. Alexander Walker, the film critic of the London Evening Standard, once explained to me: “The reason we British have the word queue is that the French had no further need of it.”

There is always a certain hysteria anyway when people are crowded up at the door of a screening at Cannes, especially a press screening. Many of them absolutely must see a given film in order to write about it, or interview someone in it, and so they arrive early so they can spend half an hour gazing through glass doors at imperturbable guards inside. Finally the guards open the doors, responding to some festival timetable not discernible to anyone else, and then people push violently toward the opening. One year the crush was so bad at the premiere of Bertolucci’s “1900” that a man was literally pushed through a plate glass window. Alexander Walker had a door slammed on his hand in 1979, while trying to show his press card to one of the uniformed goons. I personally set some sort of unique record, by failing to ever successfully attend a Henry Jaglom film at Cannes. The doors were slammed in my face four different years, and at the premiere of “Can She Bake a Cherry Pie?,” Jaglom saw me at the back of the crowd, moved forward confidently to use his director’s clout to get me in, and heard the doors slam shut behind him.

“Roger Eggplant!”

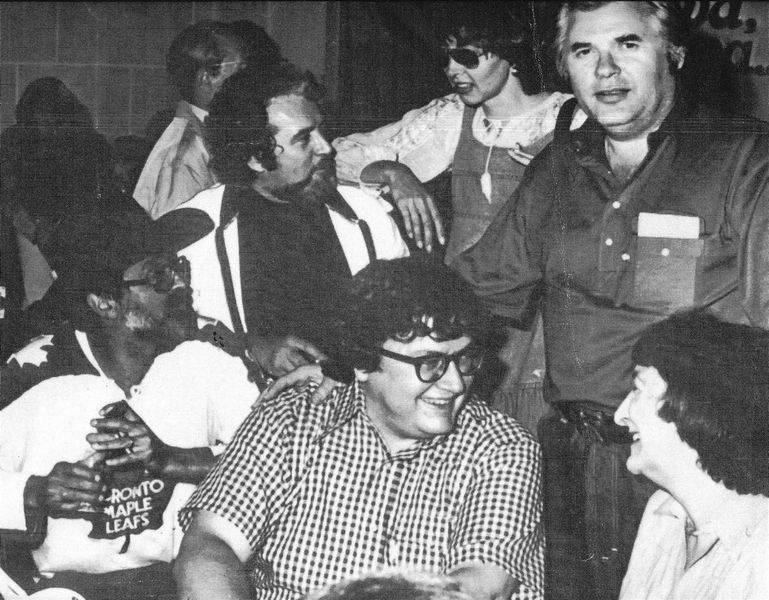

Billy (Silver Dollar) Baxter is the most interesting character I’ve ever met at Cannes, and indeed he helped introduce me to the festival. The first time that I walked into the Majestic Bar in 1977, I had little notion of how anything worked, except that however it worked, I could not afford it. Everybody was very slick and European and rich, and they all knew each other, and they belonged in a movie by Antonioni and I belonged in one with Huntz Hall. I was standing inside the door of the bar, looking at the beautiful people, when I heard a voice, loud and clear, not six feet from me.

Irving! Brang ’em on!

I turned and saw a man with silver hair, a complexion pink as a baby’s skin, a yellow golf shirt, a Marlboro gimme hat, blue jeans, Hush Puppies, and a diamond-studded belt buckle big as a paperback book.

Irving! Brang ’em on! Johnny Walker! Red label! Generous portion! Clean glass! Pas de soda! Pas de ice! And clean up this shit and get some olives and potato chips over here, on the double!

Billy saw me in the doorway. He was sitting with Kathleen Carroll, the film critic of the New York Daily News, and she told him who I was.

“Roger Eggplant!” he shouted. “Have a seat! Irving!”

Ruder than French

In America, Billy Baxter might perhaps have been considered loud, even rude. In France, he had found the way around the French tendency to ignore or patronize visiting speakers of English. He was so loud, so outrageous, and so uninhibited that there was only one thing to do with him, and that was to serve him, so that he would shut up. After a few years, the Majestic waiters actually seemed to develop an affection for Baxter; other customers might tip better, but none tipped more visibly, or demanded more service. Perhaps they could identify with Billy’s chutzpah more than with the smarmy ingratiations of the Americans who are intimidated by Cannes and actually try to be nice to the waiters.

For several years, until he finally stopped attending Cannes in 1984, Billy Baxter was the epicenter of the festival for many people. His gift was that he cut through the crap. Snotty foreign directors, uncertain exactly who he was, allowed themselves to be led by the elbow or sometimes by the ear to a table where Billy would introduce them to obscure film critics, would-be starlets, and maître d’s from restaurants he had visited earlier that evening. In the casinos of Cannes, Billy explained his various unbeatable systems to anyone who would listen, and once caused a crisis at the Casino des Fleurs when he walked out with a 40,000-franc chip in his pocket. The administration of the casino sent a cropuier in a tuxedo into the bar of the Majestic to ask Billy to cash in the chip so that they could balance their books for the night, and Billy tried to buy the man a drink while explaining that he planned to keep the chip as a memento and have it laminated and turned into a belt buckle.

I still do not fully understand how Baxter convinced Lord Lew Grade, then the millionaire boss of England’s largest film conglomerate, to take Billy and a group of his friends on the inaugural cruise of his lordship’s brand new yacht. But there are a lot of things I do not understand about Silver Dollar Baxter, one of them being how a character from out of the pages of Damon Runyon could survive and even flourish in these pale days of ordinary people.

The origins of Silver Dollar Baxter

Silver Dollar Baxter got his nickname because for many years he arrived at Cannes with 2,000 American silver dollars, which he bestowed as tips. “You think this is something?” he once explained. “You shoulda seen what I paid in air freight to get them over here. I gotta send them in advance, because you try to get through customs with 2,000 silver dollars, you’re gonna be explaining things for hours. My banker handles it.”

“Do you call your banker Irving?”

“Yeah. Irving Trust.”

Baxter’s silver dollars are still held as lucky charms in the pockets of many of the waiters in Cannes, who have waited in vain in recent years for his return. At the Majestic, he brought excitement to the room. Even during the darkest days of the 25-cent franc, when a round of drinks at the Majestic could easily run $100, Billy grabbed the checks.

So great was his generosity that certain other customers began to take his hospitality for granted, and would sign his room number to their bar bills. To stop such fraud, Billy appeared at the 1982 festival with a small rubber stamp, which reproduced his signature and added underneath, “None genuine without this mark.”

Impeccable credentials

Billy’s genius was to boldly cut through bureaucracy with his own loud personality. In 1980, he pulled off his single greatest stunt by issuing his own credentials to the festival. This was in connection with a Cannes television special that he had convinced Lord Grade to underwrite.

“These guys over here are all hung up on anything that looks official,” he said. “They issue you a permit to take a shit. But half of the guards can’t read, and besides, they don’t got the time, because there’s always a riot going on.”

Taking advantage of this situation, Billy had a New York job shop print up dozens of official-looking credentials for the “World International Television Network” (“I shoulda added ‘Global,'” he moaned). He attached the photographs of his friends to the cards, had the cards laminated, and strung them on a chain so they could hang it around their necks. Only guards with sharp eyes might be expected to read the personal details on the cards, and learn that each and every one of Billy’s friends was exactly the same height, weight, and age, and had the same hair and eye color. Billy signed all of the credentials himself. “What this document certifies,” he chortled, “is that it is worn by the bearer.” I still have mine. It got me into screenings where the guards were waving away people with genuine tickets.

Miss Boop-a-Doop-a-Dee

Billy had a genius for sweeping up people who had no idea who he was, and introducing them to other people he wanted to meet. “Sir Lord!” he boomed one night to Lord Grade, “meet Miss Boop-a-Doop-a-Dee from Venezuela.” Instead of remembering names, he often simply improvised them, along with identities, credits, and national origin. “She directed the winning film in last year’s festival. That’s why she gets to come to the bar in her underwear.”

Miss Boop-a-Doop-a-Dee was, in fact, Edy Williams, the starlet who has become famous for traveling all the way to Cannes every year to take off her clothes while standing in the public fountains. Lord Grade looked prepared to believe that she was a director from Venezuela. Indeed, he looked prepared to believe almost anything about her. The only thing the 75-year-old lord couldn’t believe was that he had walked into the Majestic Bar.

Booing and hissing

It is a good question … whether a director would really want his film to be seen for the first time by critics at Cannes. It will be one of dozens of films the critics will view in a short space of time, it will be seen with highly vocal audiences much given to booing and hissing, and if it is English it will have French subtitles, if it is French it will have English subtitles, and if it is any other language it will have French subtitles and other language groups will have to listen to an ad-libbed simultaneous translation through portable earphones.

And yet when a movie is really good, and really working, there is possibly no better audience for it than at Cannes. There aren’t any civilians out there in the dark: Everyone at this festival makes a living in one way or another from the movies, and so presumably loves them. My peak experiences with Cannes audiences were at the world premieres of Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” and Spielberg’s “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial,” and in both cases the audiences broke into tumultuous applause at the end, cheering the directors with an enthusiasm usually reserved for opera stars.

On the Amazone

On the evening before the world premiere of “Apocalypse Now,” Coppola sat aboard the yacht Amazone, anchored offshore. The yacht was the largest at Cannes, was illuminated at night by strings of lights, and was reached by motorboat from the Carlton pier, where on this night, six or eight critics had gathered to pay Coppola a visit. We watched as the motorboat circled lazily to pick us up.

The Amazone had been in the bay all week, a large, gray presence, and as festivalgoers hurried to their screenings they would sometimes glance out at Coppola, riding at anchor. He had gambled five years and his personal fortune on a film that was now entered in the official competition at Cannes (which meant that it could come home as a loser). He was no doubt sitting out there even now, thinking what private thoughts no one could guess. By renting the yacht and anchoring it in solitary splendor at the end of everyone’s view, he had dramatized his presence and his isolation.

Coppola’s war stories

If he was nervous that night, after we climbed aboard the Amazone, he did not show it. While the ship’s crew arranged a huge bouquet of flowers, while the steward poured wine from Coppola’s private vineyard in California, while Coppola’s parents, in evening clothes, left to attend the evening’s events ashore, the director slouched comfortably on an overstuffed sofa. He began to talk about his movie that had become a legend even before its premiere, a movie that began as a simple little war story, and grew and grew as millions of dollars were poured into the jungle locations in the Philippines, and millions of feet of film were shot, and whole villages were blown up for scenes that were later not even used. He spoke about the heat sickness, and the expensive sets that were blown away by monsoons, and the injuries and heart attacks and divorces and intrigues that had plagued the production. What it came down to, he said, was that his film itself had become an undertaking like the Vietnam War: Americans pouring men and money and sophisticated machinery into a jungle that implacably overwhelmed them.

One of the critics took out a notebook and a ballpoint, and Coppola’s publicist, Pierre Rissient, hurried over to whisper in his ear. There were to be no notes and no direct quotes. The war had taken over Coppola’s movie in more ways than he realized: He was the general giving an off-the-record backgrounder.

The End(ing)

When Coppola sneaked the film, he said, he still wasn’t sure of his ending. He defended that. He had started in theater, directing plays when he was 16 or 17 years old, and he’d learned then that when a play was almost right, you showed it to an audience, and let them re-experience it for you. When you got too close to the material, an audience could see it freshly, and you could look through their eyes. With “Apocalypse Now,” he had several different endings, some of them just a shading apart, as a shot or a line of dialogue was adjusted, but one of them was a more conventional Hollywood ending.

He talked some more, about the jungle and the movie and his ambition to found his own studio, and then it was time for us to take the speedboat back to shore. I did not suspect at the time how touchy Coppola was on this business of his ending, and what bizarre events it would inspire on the next day, the day of the official screenings.

“Apocalypse Now” played three times, to full and enthusiastic houses, and it eventually shared the Palme d’Or that year with Volker Schlöndorff’s “The Tin Drum.” When Coppola began his press conference after the morning press screening, he was already a winner in the eyes of the journalists. But then he began to make extraordinary statements. One of them was a blanket condemnation of the entire American press—not just critics, but the press as a whole—as “decadent, unethical, and lying.” Not one word of truth, he said, had ever been printed about his film during its entire troubled production history.

What inspired this amazing outburst? The week before, Coppola had scheduled three sneak previews of his film, each slightly different, in Los Angeles, and had agreed to allow critics to attend them if they would honor an embargo—no reviews until the official opening of the Cannes version. But most of the critics went ahead and wrote about it, and Rona Barrett had panned it. Variety had then formally announced the embargo was broken, and reviewed the film from Los Angeles, instead of waiting for the Cannes cut. In the movie business, the Variety review is often the “money review,” the one that sets the tone for a film’s commercial history, and so of course Coppola had reason to be angry. But what he did a week later in Cannes was remarkable in any context. After the press conference for print journalists, he held a later session for television. Badgered again by questions about his endings, he was finally inspired to announce that on the next day, at noon, in a local theater, he would show them his “other” ending.

The End(ing), Part 2

Nothing like this had ever been heard of at Cannes. He had the other ending back on his yacht, he said—a few more shots in which, after the passage of mystery and the solemn insanities of Kurtz, the surviving members of the riverboat crew return to their boat and move back downstream, away from the heart of darkness. This was a more conventional Hollywood resolution. During the production of the film, Coppola also shot scenes in which Kurtz’s jungle temple was destroyed by an air strike—and this scene, never in any of the final versions at Cannes, was used months later in the closing credits of the 35mm version of the film (leading to further confusion over the ending, since the 70mm road-show version came with printed credits and had no end titles).

The amazing thing was not that Coppola had another ending; key scenes are often shot in several different ways. What was amazing was the impulse that led him to bring that other ending to Cannes, and to show it. Perhaps he wanted to vindicate himself by demonstrating that the traditional Hollywood ending was unnecessary, that it was better just to leave the characters stranded there in darkness. But even if that was the case, what can be made of the public nature of Coppola’s final waffling on the film? Coppola couldn’t seem to let go. He had no ending, he had several endings, he didn’t have an ending that he was satisfied with, he had two endings that both worked. At one point (he told us on the yacht) he was shooting an ending a week.

The fact is that the “original” ending, the one Coppola showed in the official screenings at Cannes, and which was eventually seen all over the world, was a magnificent ending to a magnificent film. “Apocalypse Now” remains the best of the Vietnam movies, more effective even than “Platoon,” because while “Platoon” did a powerful job of recreating the reality of combat in Vietnam, Coppola’s film was a statement on the whole state of mind that led us into that war and kept us there—the river journey into darkness was our own national search for a goal we could never define, and thus could never discover.

Coppola’s strategic error was to ever mention that he had any sort of a problem with any ending of “Apocalypse Now.” If he had settled on an ending and released it, and kept quiet, no one would have been alerted to the “problem” and no one would have looked at the ending as if it were a problem. My theory is that he went a little bananas, out there in the bay on board the Amazone. He had worked on this film for years. He had mortgaged his home, his vineyard, his family’s future, to complete it. He had taken the supreme risk of placing it in competition—something he did not need to do, since his 1974 film “The Conversation” was a Cannes winner, entitling him to play out of competition. His hour of truth was approaching, and some obsessive streak of honesty forced him to blurt out that he just didn’t know which ending to use. So he showed them both, one in the Palais, one in a little rented theater on the rue d’Antibes. It was one of the strangest episodes in the recent history of Cannes.

From Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook (1987) by Roger Ebert. All rights reserved.