Allegories have trouble standing for something else if they are too convincing as themselves. That is the difficulty with “The Tin Drum,” which is either (a) an allegory about one person’s protest against the inhumanity of the world, or (b) the story of an obnoxious little boy.

The movie invites us to see the world through the eyes of little Oskar, who on his third birthday refuses to do any more growing up because the world is such a cruel place. My problem is that I kept seeing Oskar not as a symbol of courage but as an unsavory brat; the film’s foreground obscured its larger meaning.

So what does that make me? An anti-intellectual philistine? I hope not. But if it does, that’s better than caving in to the tumult of publicity and praise for “The Tin Drum,” which has shared the Grand Prix at Cannes (with “Apocalypse Now“) and won the Academy Award as best foreign film, and is hailed on all fronts for its brave stand against war and nationalism and in favor of the innocence of childhood.

Actually, I don’t think little Oskar is at all innocent in this film; a malevolence seems to burn from his eyes, and he’s compromised in his rejection of the world’s evil by his own behavior as the most spiteful, egocentric, cold and calculating character in the film (all right: except for Adolf Hitler).

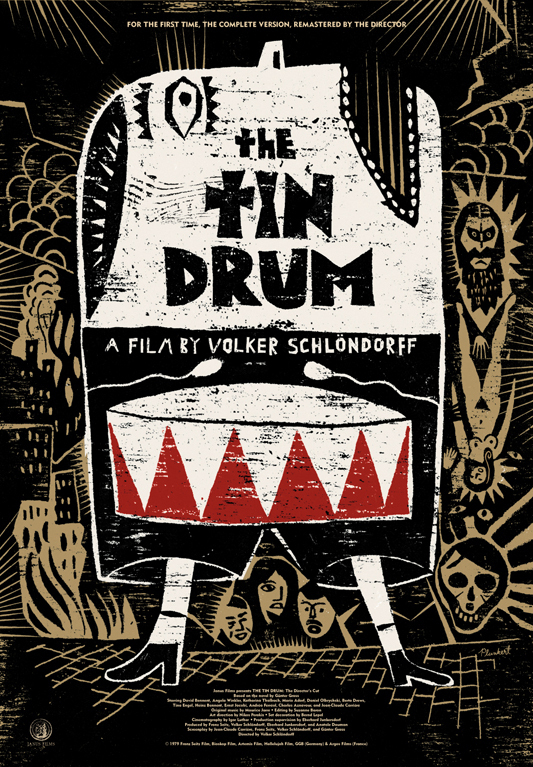

The film has been adapted by the West German filmmaker Volker Schlondorff from the 1959 novel by Gunter Grass, who helped with the screenplay. It chronicles the career of little Oskar, who narrates his own life story starting with his mother’s conception in a potato patch. Oskar is born into a world divided: in the years after World War I, both Germans and Poles live in the state of Danzig, where they get along about as well as Catholics and Protestants in Belfast.

Oskar has fathers of both nationalities (for reasons too complicated to explain here), and he is not amused by the nationalistic chauvinism he sees around him. So, on his third birthday, he reaches a conscious decision to stop growing. He provides a plausible explanation for his decision by falling down the basement stairs. And for the rest of the movie he remains arrested in growth: a solemn-faced, beady-eyed little tyke who never goes anywhere without a tin drum which he beats on incessantly. For his other trick, he can scream so loudly that he shatters glass.

There is a scene in which Oskar’s drum so confuses a Nazi marching band that it switches from a Nazi hymn to “The Blue Danube.” The crashing obviousness of this scene aside, I must confess that the symbolism of the drum failed to involve me.

And here we are at the central problem of the movie: Should I, as a member of the audience, decide to take the drum as, say, a child’s toy protest against the marching cadences of the German armies? Or should I allow myself to be annoyed by the child’s obnoxious habit of banging on it whenever something’s not to his liking? Even if I buy the wretched drum as a Moral Symbol, I’m still stuck with the kid as a pious little bastard.

But what about the other people in the movie? Oskar is right at the middle of the tug-of-war over Danzig and, by implication, over Europe. People are choosing up sides between the Poles and the Nazis. Meanwhile, all around him, adult duplicity is a way of life. Oskar’s mother, for example, sneaks away on Thursday afternoons for an illicit sexual interlude. Oskar interrupts her dalliance with a scream that supplies work for half the glassmakers in Danzig. Does this make him a socialist or an Oedipus?

Soon after, he finds himself on the road with a troupe of performing midgets. He shatters glasses on cue, marches around in uniform and listens as the troupe’s leader explains that little people have to stay in the spotlight or big people will run the show. This idea is the last Oskar needs to have implanted in his mind.

The movie juxtaposes Oskar’s one-man protest with the horror of World War II. But I am not sure what the juxtaposition means. Did I miss everything? I’ve obviously taken the story on a literal level, but I don’t think that means I misread the film as it stands.

If we come in armed with the Grass novel and a sheaf of reviews, it’s maybe just possible to discipline ourselves to read “The Tin Drum” as a solemn allegorical statement. But if we take the chance of just watching what’s on the screen, Schlondorff never makes the connection. We’re stuck with this cretinous little kid, just when Europe has enough troubles of its own.