Look,

I’m tired of him, too.

I’m

even more tired of defending him—to myself, most of all. Armond White doesn’t

make it easy on those of us who like, or at least tolerate, him. He’s

needlessly combative, explosively arrogant and self-defensive in equal

measures, and disingenuous in his argumentation against those who disagree with

him. Your Latin dictionary should probably have a picture of him next to the

definition of ad hominem. Over the last decade, his writing has

become increasingly opaque, often to the point of incoherence, while he’s

become more and more caustic and condescending about his vagaries. (“If

you can’t understand my florid ineloquence and inarticulate profusions,

it’s your fault,” he seems to say.) He’s grandiose in his

opinions while offering few substantive details to buttress said opinions. His

sentences seem coated in butter; the more you try to latch onto their meaning,

the messier and more slippery they get.

But a defense is still required. Here it is.

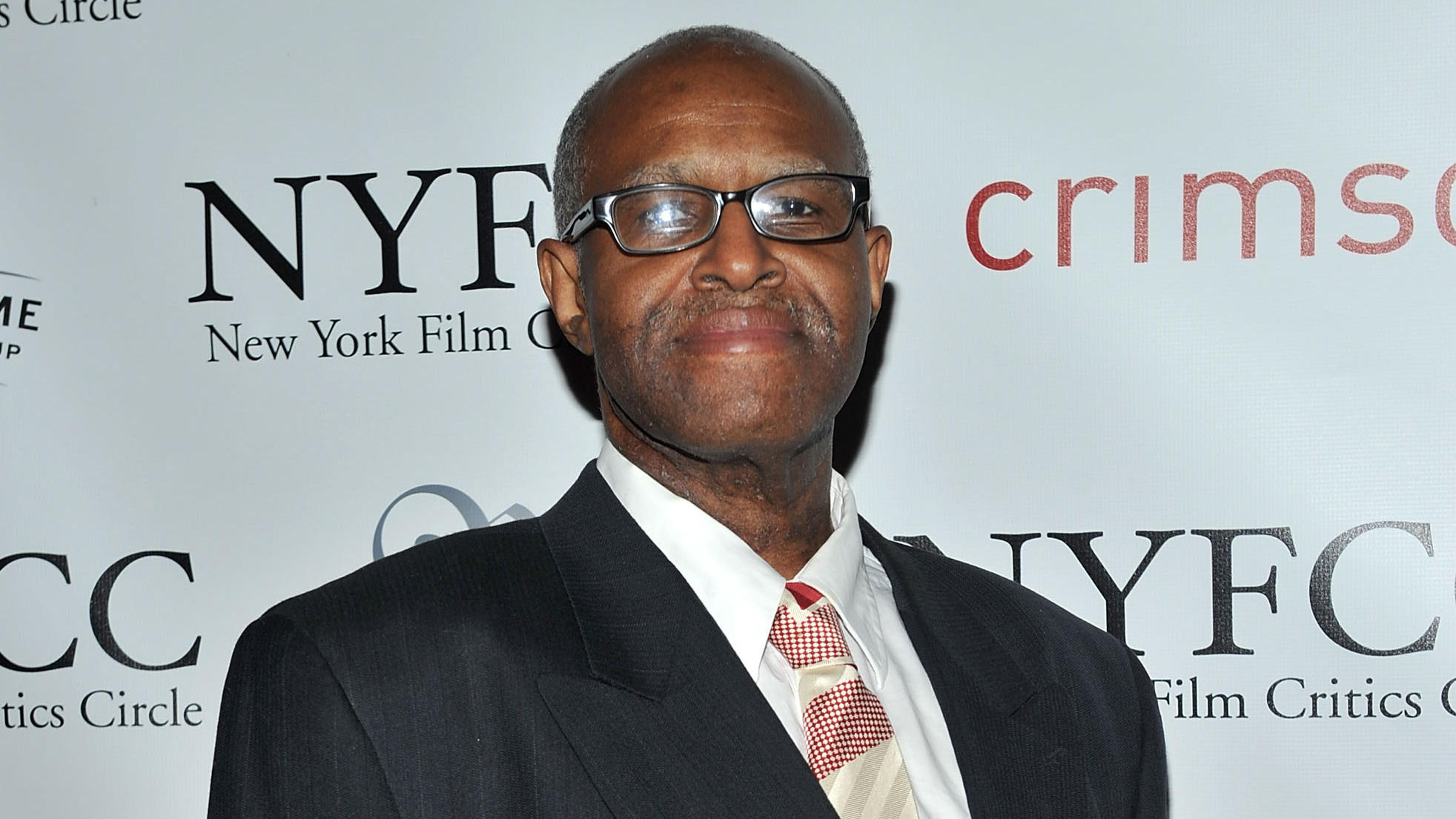

Armond White is an important, distinctive, and (okay, I’ll

say it) necessary voice in film criticism. He’s no troll, and he’s one of the

few critics capable of noting the inherent—and latent—racism of much of cinema

and its discourse. In his writing at City Arts, Film Comment and the now-defunct City Sun and New York Press (where he wrote alongside Matt Zoller Seitz and Godfrey Cheshire), he has provided a rare black voice, and perhaps an even rarer conservative voice, to film/video commentary. White is fluent in pop culture outside of

cinema, academic theory, religion and politics, and brings it all into his

writing. He throws brickbats at stuff I

love, sure, but I’ve got thick skin, and his provocations serve to

jostle me out of received opinions and consensus feedback.

If

nothing else, Armond White—like almost no one else in today’s mainstream

American film criticism—makes me consider why I like what I like, and to

learn to defend it against his attacks. In his essays, he points the way to

classics (American and otherwise) that I might not have otherwise considered,

and unearths underdog gems on a regular basis. He makes seemingly bizarre

juxtapositions that, more often than not, grow to feel correct upon reflection,

and that show the ways in which cinema is itself a bizarre concatenation of

different modes, technologies, discourses, and genres. Just as White’s chosen

art form is hybrid, so too is his criticism, and it’s odd to note how rare this

trait is in film commentary.

And

now, after serving as its chair more than once, Armond White has been kicked out of the New York

Film Critics Circle, basically

for making an ass of himself at the NYFCC awards banquet during a presentation

for “12 Years A Slave.” (White was not a fan.) Now, to be fair, he probably was disruptive and

uncivil. He’s made a habit of that in his prose for 30 years, calling those who disagree with him “fools,”

“charlatans,” and “simpletons.” He’s no stranger to

personal attacks and look-at-me theatrics.

But

I don’t actually know what went down at that banquet and neither, in all

likelihood, do you. Accounts vary. White’s denial of the allegations is predictably self-serving and incoherent. Available recordings aren’t

conclusive.

Still,

let’s be honest. Dude’s being kicked out for heckling?

Are

we adults here?

A

rundown: A Very Important Movie About A Painful Subject—that I admittedly have

not seen, so have no dog in that fight—gets booed by a dissenting critic, a

position that said dissenting critic is entitled to take. Dissenting critic

then sees the film critics association to which he belongs extol the movie’s

virtues, and decides to sneer further at the obtuseness of those who praise the

Very Important Movie at an event that happens to have an open bar. He then gets excommunicated from said

society for heckling a film and director that

he’s made it clear that he hates.

All

of this is complicated by the fact that said Painful Subject is slavery, and

thus intrinsically tangled up in race, and the trauma that this country has

inflicted upon itself from its genesis. The dissenting critic is

black. The filmmaker is black. The film’s subject is, largely,

blackness. Almost everyone else in the story is white.

Presumably,

of course, the dissenting critic (Armond White) is overly rude, disrespectful

and, when responding angrily to allegations that he denies about himself,

sensitive. Of course. Because no white critic has ever responded overbearingly

to a black writer’s criticisms of white discourse. No black critic has ever had

reason to think whites praise a “black” movie for all the wrong,

patronizing, soul-crushing reasons.

I’m

not defending White’s awards banquet razzing of

“12 Years a Slave,” which I have every reason to think happened, based on White’s own record of rowdiness at these dinners, and as a public figure generally. From a public-relations standpoint, the man

is his own worst enemy, and his assertion that his peers’ censure is “a shameless attempt to squelch the strongest voice that exists

in contemporary criticism” makes my head hurt. Even among prominent

African-American critics, I’m not convinced White is the most incisive. There’s Elvis Mitchell, Steven Boone, Odie Henderson and Wesley Morris, formerly of

The Boston Globe, now of Grantland, and one of a handful of film critics of any

color to win the Pulitzer for criticism.

Nevertheless,

no other African American critic incites, either through their writing or their

public remarks, the kind of ire that has accompanied White throughout his

career.

There’s no point arguing whether White’s writing or his public persona

is the bigger irritant, because his entire career—beginning with his 1980s run

at the City Sun—has been based on

conflating the two. Following the model of Pauline Kael, whom White

acknowledges as a key influence, he makes his personal investment in his

criticism part of the package.

But it is still worth considering, however briefly, the notes that White strikes in

his writing, and the actual arguments that he makes, and then compare them to

similar sentiments expressed by other people who aren’t as widely reviled, and

are in fact beloved precisely because they challenge conventional thinking.

When we do that, we may have to admit that, however self-serving it may be,

there’s something to White’s protestation that he’s being held to a unique

standard and treated with singular harshness—that perhaps, as Nirvana sang,

“just because you’re paranoid / doesn’t mean they’re not after you.”

Which brings us to Jonathan

Rosenbaum, formerly of The Chicago Reader and one of the most politically

concerned and globally trenchant of working critics. Rosenbaum called McQueen’s film “an arthouse exploitation gift to masochistic guilty liberals

hungry for history lessons, some of whom consider any treatment of American

slavery by a black filmmaker to be an unprecedented event, thus overlooking

Charles Burnett’s far superior ‘Nightjohn.'”

This sentiment’s pretty much what White wrote about McQueen’s movie, down to the

Burnett reference. But Rosenbaum wrote it two months after White, and had the

privilege of being, um, white, and so he wasn’t blamed for wrecking

the film’s Rotten Tomatoes percentage, much less written off as a troll who was playing contrarian to generate page clicks.

Speaking

of which: White is often blasted as a critic who doesn’t believe

half the things he writes, and intentionally goes against the critical grain

to garner attention for himself. This claim is belied by the NYFCC’s own

evidence. Yes, McQueen may have jeered McQueen’s nod as Best Director. But

“American Hustle“, the group’s choice for best film, is one that White praised highly.

And as a commenter on the Hollywood Reporter’s story about the brouhaha pointed out, it’s not as if White’s list of

canonical films is absurd, or even terribly adventurous.

Here is the

contrarian White’s Top 10 list from the 2012 Sight & Sound poll:

“L’Avventura'” (1960) Michelangelo Antonioni

“Intolerance” (1916)

D.W. Griffith

“Jules

et Jim” (1962) François Truffaut

“Lawrence

of Arabia” (1962) David Lean

“Lola” (1961)

Jacques Demy

“Magnificent

Ambersons, The” (1942) Orson Welles

“Nashville” (1975)

Robert Altman

“Nouvelle

Vague” (1990) Jean-Luc Godard

“The Passion

of Joan of Arc” (1927) Carl Theodor Dreyer

“Sansho

Dayu” (1954) Mizoguchi Kenji

We

can quibble over lists, and critics make entire careers out of doing such

things, but White’s canon seems respectful and mainstream enough to my eyes.

Antonioni, Dreyer, Mizoguchi, Godard, Truffaut, Welles—these aren’t outré choices. Even if they were, are we seriously claiming White as a

knee-jerk contrarian because he dared to dislike “12 Years a Slave”,

and to (allegedly) say so publicly? Or because he goes against the number-crunching

at Metacritic?

Again,

are we actually adults here?

I

know, I know. The knee-jerk to White’s knee-jerk is that he (gasp!) actually likes Michael Bay’s cinema, especially “Transformers“. And, yeah, I

think that franchise is crappy, too. But he’s entitled to think otherwise, and

we shouldn’t dismiss White’s entire critical oeuvre just because he likes a guy

whose reputation is being rehabilitated as the vanguard of “vulgar auteurism,” anyway. If we can still anoint Roger Ebert

as a critical saint after giving three stars to “Tomb Raider” none to Alex Cox’s “Walker” (a film that’s now part of the Criterion

Collection), then perhaps we should let White own a few outlying

opinions without relegating him to the dustbin.

Critics

make mistakes. They like movies that popular audiences dismiss. They go against

the grain, in part because they have a deeper knowledge of cinema than most

audiences. Sometimes they’re wrong. But sometimes they know things, and see

things, that the rest of us don’t.

White is informed about cinema. More importantly, he cares

passionately about it. If he contends in his initial review that “12 Years

a Slave” is so hateful that it “didn’t need to be filmed this way and

I wish I never saw it,” why should we be surprised that he excoriates the

praise heaped upon it? And why, given his revulsion, should we insist that he

pretend he’s all right with the praise, solely to preserve decorum at a

tuxedoes-and-canapés event?

And

even if you accept that White—or if not White, the tablemates that he failed to

control—behaved

badly at an awards ceremony, does that offense necessitate an emergency

meeting, much less an outright dismissal from a group in which was a three-time president and dues-paying member? Isn’t this a behavioral issue that could have been solved

by disinviting White and his entourage from future dinners, or perhaps asking the wait

staff and security at next year’s dinner to keep an eye on White’s table and

nip any problems in the bud before they had a chance to become problems?

Even

if we agree that rude behavior at awards dinners is unacceptable—and I do—what

does it have to do with anything beyond the dinners themselves?

Nothing.

White

has always lacked decorum, often to his detriment. He can be appallingly

childish. But this contretemps exposes a deeper, more systemic childishness, an

unwillingness to tolerate dissenting opinion under the guise of promoting

“respect” and decorum. Sometimes it is decorum itself that is

stifling, that shuts down debate, that maintains a harmful status quo, and that needs to be dismantled so that rigorous,

full-bodied, multifaceted criticism can flourish. Isn’t that what a critics’

circle should be striving toward?