The world lost one of its most beloved comedians this past Sunday with the death of Jerry Lewis. Scott Jordan Harris penned our obituary, but we wanted to let other members of our staff share their thoughts on such an influential, legendary director.

PABLO VILLAÇA

Jerry Lewis was one of the main reasons I fell in love with the movies. When I was a kid, his movies were a fixture of Brazilian TV during the afternoons—and I can vividly remember how they made me feel; it was fascinating to watch that man-child and his grown-up, charming, singing best friend living so many adventures and facing adversities by supporting each other. Lewis' solo movies were also a reason of constant delight and I soon began to associate Cinema with pleasant, happy feelings. However, it didn't take long for them to also start teaching me how film involved more than just a script and a few actors: watching "The Ladies Man," I became aware of the importance of production design; with "The Bellboy" and "Who's Minding the Store?," I realized how sound could be powerful; and with most of the rest I understood how comedy could also break your heart. Lewis was a genius as a comedian, as an actor, as a director—well, as an artist. He was 91 years old, but he left us too early. This loss stings me deeply and that shows his force and his legacy as a human being. I wish I believed in an afterlife just so I could imagine Lewis finally reunited with his "pardner" once again.

DONALD LIEBENSON

In 1963, I was seven years old. Our family was on vacation in California. There was a two-screen movie theatre near our hotel. On one screen, "Bye Bye Birdie." On the other, "The Nutty Professor." The poster for "The Nutty Professor" made it look like a horror film ("What did he become? What kind of monster?") I was scared to go into that theatre, but my father said to me, "That's Jerry Lewis. If Jerry Lewis is in it, it's going to be funny." Much of my love for movies and comedy can be traced directly to Jerry, whose Paramount comedies, with and without Dean, were staples on NBC Saturday Night at the Movies, and at Saturday matinees at Highland Park's venerable Alcyon Theatre.

When I learned of his passing, I did not go directly to the classic comedies of my childhood, "The Errand Boy," "The Disorderly Orderly," or "The Family Jewels," I went to my favorite scene of his from the underseen "Funny Bones," in which his character, a comedy icon, delineates for his son, a comedy flop, the difference between "a funny bones comedian and a non-funny bones comedian." There is a lifetime of hard-earned wisdom in his delivery of, "We were funny people ... we had funny bones."

SUSAN WLOSZCZYNA

Judging by the comments and obits on my social media feed about comedian, actor, filmmaker and philanthropist Jerry Lewis, I am not alone with my love-hate relationship with this divisive legend who left a giant mark on pop culture. I idolized him for a while as a grade-schooler because I could relate to his crazy voices, elaborate pratfalls and infantilized gaze at the world around him. I recall going to the drive-in the early ‘60s with my parents and my older brother for a triple bill of “The Errand Boy,” “Cinderfella” and “The Bellboy.” They all started falling asleep at some point but I protested when they wanted to leave after the second film. We stayed. I watched. They snoozed. I laughed.

When I got older, I also developed a fondness for “The Nutty Professor,” which encapsulated the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde psychological conundrum of what it meant to be a man in the era of the ring-a-ding-ding Rat Pack and the Kennedy clan. I confess to dating a musician in my grad-school years very briefly who assumed the stage name of Buddy Love just for that reason. And, yes, he was a jerk.

That rather sophisticated upgrade in his comic vision convinced me that Lewis had something more on the ball than just pulling faces. But it took Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy,” a dark drama about celebrity-hood and idol worship that very much played off the star’s aloof off-stage persona that made me and many others to reconsider Lewis in a more serious way. The guy could drop the goofy act and actually act.

But it was that maudlin annual ritual of watching his self-gratifying TV performance as a do-gooder every Labor Day during his Muscular Dystrophy telethon that truly drove me crazy. Yes, he was making a difference but also wanted the public to observe every minute of it. It was train-wreck TV writ large. Still, I used to make a point to always try to watch Lewis sing “You’ll Never Walk Alone” from one of my favorite musicals, “Carousel,” usually with tears streaming down his face after they announced the final total that was raised.

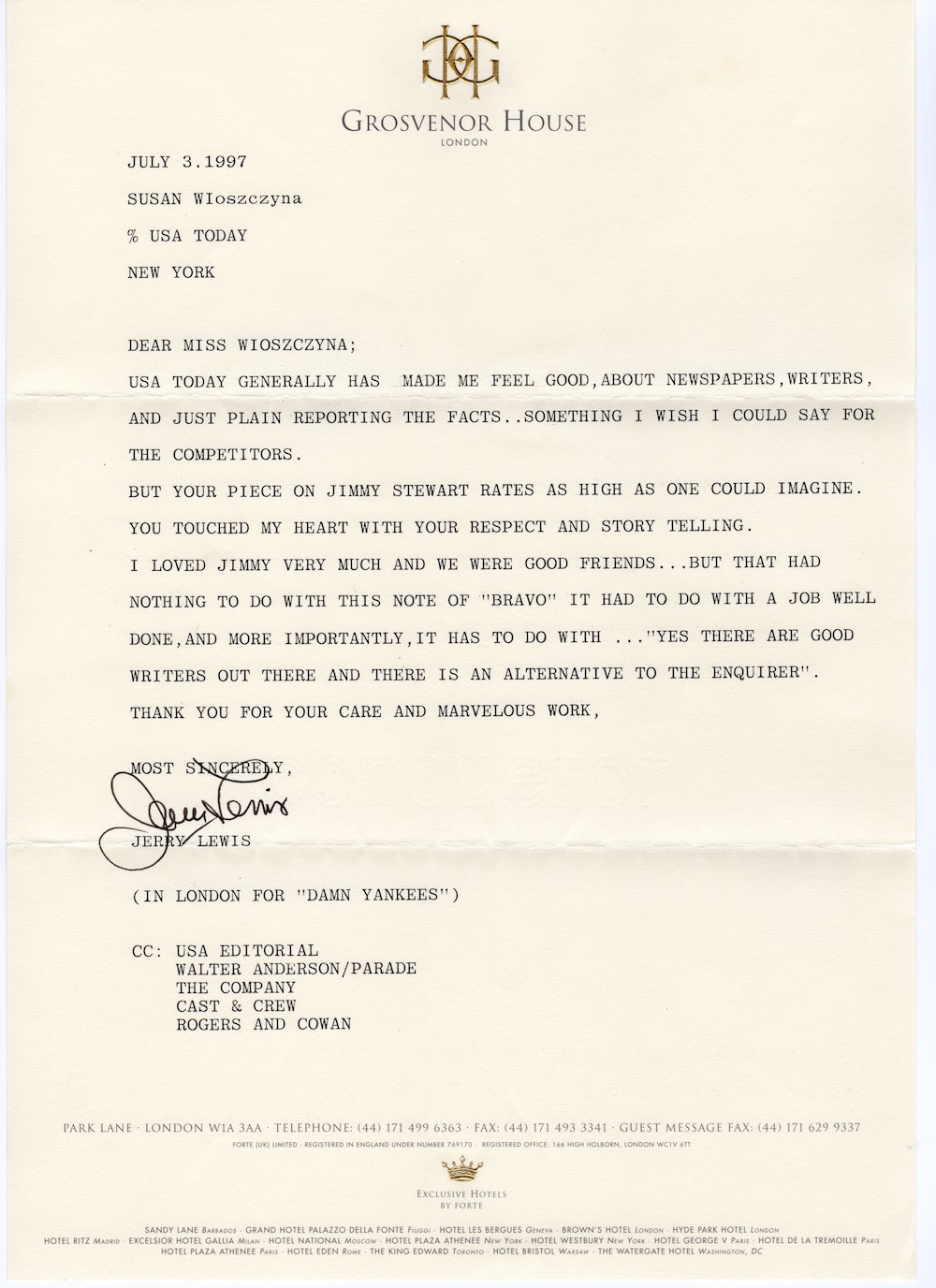

When I went to work at USA TODAY in the ‘80s, my fellow film critic and writer Mike Clark was, among other things, a world-class worshiper of Lewis and his onetime partner Dean Martin. So anything that involved either of them was definitely on his beat. So imagine my surprise when, after my rather lengthy tribute to James Stewart ran on the front page of the paper after his death on July 2, 1997, I received a letter from none other than Jerry Lewis.

What he wrote actually made me teary-eyed. Such a generous open-faced expression of praise from a famous person is a rarity, especially when the matter at hand isn’t even about them. I realized then that this class clown was quite capable of being a classy act. While I am still not a big fan of much of his work—although I made a point to see him onstage in “Damn Yankees,” and was blown away—I became a bigger fan of the man himself that day.

PETER SOBCZYNSKI

If the life of the late Jerry Lewis was to be examined solely on the basis of his contributions as a comedian, his place in the cultural firmament would be secure. In a career that stretched back to the days of vaudeville and which would cover radio, television, film and Broadway, he made audiences around the world laugh for decades and would also inspire generations of of comic performers to emerge in his wake. And yet, his other contributions as a filmmaker, an author, a dramatic actor and a humanitarian were so extraordinary that even if one were to somehow strike all of his comedic performances from the record, you would still be left with a career resume of enough import to make most others seem kind of puny by comparison. Put it this way—while the word “legendary” usually comes across as just another empty honorific when used to describe most entertainers, it almost seems too puny and inadequate to fully and fairly describe Lewis and his accomplishments.

He was, first and foremost, a comedian and he was indeed one of the greats. When he burst onto the scene in an act alongside Dean Martin, audiences could not believe what they were seeing. With his wheedling voice, rubber face and facility for wild slapstick, especially in comparison to the sense of holy cool represented by Martin, it was as if the long-suppressed id of the post-war American psyche could no longer be contained and finally exploded in ways that many found to be breathtakingly hilarious and other found to be crass, vulgar and juvenile (a dichotomy that would continue to endure throughout his career). And yet, if you watch a film like “Hollywood or Bust” or “The Ladies Man” or, most famously, “The Nutty Professor, you cannot help but notice Lewis' incredible sense of control in regards to performing—they may have looked at times like the ravings of a madman but his best work had a genuine grace and finesse behind it that would put most comedic performers of any era to shame. His work in “The Nutty Professor,” for example, must have been fiendishly complicated for him on any number of technical and emotional levels (for a comedian whose weakness was probably his unabashed desire to be loved and accepted, to do a film taking that very concept to its absurd and sometimes frightening extremes must have been a challenge). But his deftness in switching between the adorably awkward Julius Kelp and the slick sleaze ball Buddy Love was so nimbly handled that it deserves to go down as one of the great comedic performances in screen history.

Like most comedians, Lewis wanted to be taken more seriously from time to time and while his efforts in this area were not always successful—his ultimately aborted Holocaust drama “The Day the Clown Cried” being the prime example—he did have his share of triumphs in this area as well. His most famous dramatic turn came in “The King of Comedy,” which he was asked to go toe-to-toe with Robert De Niro (at the point when his status as the Great American Actor was at its peak) under the direction of Martin Scorsese to play a thinly disguised version of himself being pestered and ultimately kidnapped by a psychotic fan. Even the most skilled of dramatic actors would find that a virtually impossible challenge and yet Lewis pulled it off to such a stunning degree that the fact that he did not even earn an Oscar nomination for his efforts—let alone win the award he so richly deserved. Although few of his subsequent dramatic efforts—films like the cult oddity “Arizona Dream,” the British charmer “Funny Bones” and the recent indie drama “Max Rose” and appearances on the television shows “Wiseguy” and “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit”—received the same amount of notice as “The King of Comedy,” they nevertheless proved that his performance there was no flash in the pan.

As his artistic ambitions flourished alongside his popular success, Lewis began moving behind the camera to work as a director as well as an actor, a relative rarity in those days in general and almost unheard of for a comedian not named Charlie Chaplin. Not only would Lewis’ efforts as a director pave the way for the likes of Mel Brooks and Woody Allen (the latter of whom was so enthralled by Lewis’s talent that he asked him to direct “Take the Money and Run”) but it would reveal him to be uncommonly skilled in that area as well. Most screen comedies until that time were not especially cinematic—they tended to plop down the camera where it could best capture the action and that was it. Lewis, on the other hand, was interested in exploring the possibilities of the medium by utilizing the tools he had at his disposal in formally innovative and oftentimes hilarious ways that could enthrall a roomful of super-serious cineastes and a theater of people looking for entertainment in equal measure.

His directorial debut, “The Bellboy” is 70 minutes of pure goofiness that is arguably the funniest film he ever made and “The Nutty Professor” is enough of a classic that even Lewis’s detractors are usually willing to give it some slack. It is too bad that he retired from directing in 1983 after making “Smorgasbord”—an uneven film that nevertheless contains at least one scene, in which he struggles to contend with the recent waxed floor of an office, that might be the funniest bit of slapstick he ever did on film—because the mind boggles at the thought of what he might have accomplished using the latest developments in CGI technology. In the late '60s, he found himself teaching a class on the various aspects of filmmaking at USC and his lectures formed the basis of a 1970 called The Total Filmmaker that remains one of the best books covering the entire process of making a film that I have ever read. (In the end, he specifically cites one young filmmaker as being destined for greatness despite having only one short film to his name at the time—a then-unknown Steven Spielberg.)

And now, he is gone and while that news does not exactly come as a surprise in theory—he was 91 years old and had been in poor health in recent years—it will still come as a massive blow to anyone with even a trace interest in popular culture in general and comedy in particular. Lewis inspired millions of laughs from moviegoers around the globe, raised millions of dollars through his telethons for Muscular Dystrophy that used to be a Labor Day staple and even in his later years, he was still capable of the occasional triumph—after numerous failed attempts to get there over the years, he finally had a genuine Broadway hit in the '90s in a smash revival of “Damn Yankees” and wrote a fascinating memoir of his years working with Dean Martin. Simply put, Jerry Lewis was an American original. And while many have tried to copy what he has done over the years and will no doubt continue such attempts for decades to come, there will never be another quite like him.