“American Masters: Inventing David Geffen“ premieres Tuesday, Nov. 20th at 8:00pm on PBS. (Check local listings.) It can also be viewed, where available, via PBS On Demand.

It was my good fortune to be working at Microsoft when the big announcement was made in March of 1995: Microsoft was entering into a joint venture with DreamWorks SKG, the new film studio and entertainment company founded the previous year by mega-moguls Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen (the “SKG” in the company’s original moniker). At the time, Microsoft dominated the booming business of multimedia publishing, and the group I was working in, nicknamed “MMPUB,” was producing a dazzling variety of CD-ROM games and reference guides. As an independent contractor I was the assistant editor of Cinemania, a content-rich, interactive movie encyclopedia (later enhanced with a website presence) that was an elegant and in some ways superior precursor to the Internet Movie Database.

Announced with much fanfare, the new partnership would be called DreamWorks Interactive, a well-funded source for state-of-the-art computer games and interactive media. Spielberg, Katzenberg and Geffen had just finished a press conference with Bill Gates on the Microsoft campus in Redmond, WA, and the Cinemania team (led by editor Jim Emerson, now the editor of RogerEbert.com) was thrilled to learn that “SKG” were going to visit the MMPUB building to celebrate their promising new partnership.

(AP photo)

Spielberg was Spielberg: Youthfully excited and eager to dominate yet another branch of the entertainment industry. Katzenberg was the “new kid” with something to prove, vengefully motivated to eclipse Michael Eisner, his former boss at Disney, after they’d infamously locked horns in epic contractual warfare. Spielberg and Katzenberg spoke with wide-eyed enthusiasm in our building’s glassy, sunlit atrium, but it was Geffen, quietly listening to his partners, who captured my attention. Geffen didn’t have to engage in cheerleading; his power in the entertainment industry was so deeply entrenched that he could simply sit back and let his partners give their sales pitch. “S” and “K” were dynamic figures to be sure, but it was Geffen’s charisma that filled the room.

As we learn in Susan Lacy’s similarly captivating “American Masters” documentary “Inventing David Geffen,” 1995 was also the year that Geffen became a billionaire. In the course of his illustrious 30-year career as a top-ranking agent, manager, recording executive, film producer and philanthropist, Geffen had earned the right to keep quiet while his partners waxed ecstatic. Notorious as an intimidating, high-volume negotiator capable of ruining his enemies and empowering his friends, Geffen had risen to the level of political kingmaker whose support of Bill and Hillary Clinton — and later Barack Obama — was famously given a fictional spin in “20 Hours in L.A.”, a first-season episode of Aaron Sorkin’s popular TV series “The West Wing,” with Bob Balaban memorably playing a thinly-veiled version of Geffen.

He rarely grants in-depth interviews, so the real Geffen — now 69, openly gay and seen here in a congenially reflective mood — is a major “get” for any documentary filmmaker. As the creator and executive producer of “American Masters,” Lacy was given remarkable access to Geffen, whose skill as a raconteur could fill hours of screen time. In addition to Geffen’s generous involvement, “Inventing David Geffen” is packed with over 50 high-profile interviewees comprising a veritable who’s-who of Hollywood music-and-movie power from the late ’60s to the present.

The participation of Spielberg, Katzenberg, Neil Young, Tom Hanks, Joni Mitchell, Clive Davis, Cher and dozens of others makes it clear that Geffen is one of the most influential and widely-connected moguls in the history of show-biz. Unfortunately, Lacy’s zeal to include nearly everyone in Geffen’s orbit results in an abundance of cursory sound-bites. As a result, major players like Warren Beatty, Steve Martin and the late Nora Ephron are relegated to the film’s pre-credit prologue and never seen again. Lacy clearly preferred to include all of her interviewees, no matter how brief their sound-bites, to illustrate Geffen’s broad, impressive spectrum of powerful friends and colleagues. It’s safe to say that a film about Geffen is one of the only places you’ll ever find so many A-list personalities edited down to a sentence or two.

Given this editorial challenge, Lacy covers that biographical territory as thoroughly as possible, turning the aptly-titled “Inventing David Geffen” into a fast-paced two-hour chronicle of Geffen’s remarkable self-creation. That titular theme is immediately stated in the film’s opening quote from Geffen, who perfectly summarizes the essence of his singular career: “I’ve always thought that each person invented himself… that we are each a figment of our own imagination. And some people have a greater ability to imagine than others.”

Geffen’s vivid imagination was as intense as his focused ambition, which drew him to Los Angeles immediately after graduating from high school. Having fallen in love with Hollywood from afar, the young, dyslexic Geffen (not yet fully in touch with his homosexuality and frequently teased by classmates) was eager to escape from his native Brooklyn, where his hard-working mother had struggled as the family’s primary breadwinner.

“Inventing David Geffen” briskly charts Geffen’s meteoric rise as a talent agent and manager after he cleverly lied his way (in 1964) into a mail-room job in the New York offices of the powerful William Morris agency. Eavesdropping on agents as he delivered their mail (and getting a rapid show-biz education through his ability to read their memos upside-down), Geffen was certain he could “bullshit on the phone” with the best of them. Before long he was in business for himself, focusing all of his personal and professional attention on Laura Nyro, the gifted singer-songwriter who was the first and only client in a Geffen-repped roster that would eventually include Crosby, Stills & Nash, Linda Ronstadt, the Eagles, Jackson Browne, Tom Waits, John Lennon, Peter Gabriel, Nirvana, Guns ‘N Roses and many other artists who reflected Geffen’s uncanny knack for discovering major talent and fostering their careers.

When Nyro’s debut LP failed to meet expectations, Geffen responded with an audacious masterstroke that catapulted him to the top of his profession: He formed a 50/50 publishing-rights partnership with Nyro and signed numerous acts to record her songs, several of which became lucrative hits, including Three Dog Night’s cover of “Eli’s Coming” and a chart-topping version of “And When I Die” by Blood, Sweat & Tears. When these two Nyro songs (and “Wedding Bell Blues” by the Fifth Dimension) were Top Ten hits in the same week in 1969, Geffen convinced Nyro to sell their publishing company for a then-unprecedented sum of $4 million. Now wealthy and validated as a gifted songwriter, Nyro finally enjoyed solo success as a performer of her own compositions.

But when she signed with Columbia instead of Geffen’s newly-created Asylum Records label, her shocking decision prompted Geffen to shift into professional overdrive. It was a pivotal trauma for Geffen, and it’s fair to speculate that Geffen’s billionaire destiny was ensured by the pain of Nyro’s betrayal. Eventually, Geffen tackled the movie business with similar success, producing such enduring hits as “Risky Business” and “Interview With a Vampire” and sharing studio credit on DreamWorks Oscar-winning productions of “American Beauty,” “Gladiator” and “A Beautiful Mind.” (Curiously, the film never mentions that Nyro, who died from ovarian cancer in 1997 at age 49, was posthumously inducted into the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of fame last April, a year after Geffen’s own induction.)

Because Geffen’s life and career are so intimately linked to the artists he represented, “Inventing David Geffen” serves a twofold purpose: Geffen’s involvement guarantees a fair amount of personal revelation and authorized biographical detail, and the stellar trajectory of his career turns “Inventing David Geffen” into a concise, contemporary history of the west-coast entertainment industry from the late ’60s to the ’90s.

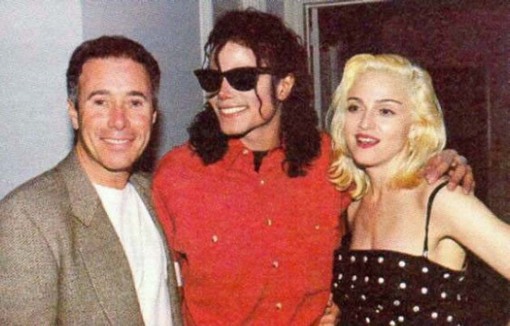

Following the “American Masters” template that Lacy created, “Inventing David Geffen” doesn’t shy away from controversy, as when Geffen unsuccessfully sued Neil Young for making “uncommercial” records, or his very public rejection of the Clintons in favor of Obama. Geffen’s first and only heterosexual relationship, with Cher in the disco-trendy ’70s, is also examined — with Cher’s happy recollections. A false-alarm cancer diagnosis provided another dramatic turning point, as did the loss (to AIDS) of hundreds of Geffen’s gay friends and acquaintances including choreographer Michael Bennett, who had directed Geffen’s triumphant 1981 Broadway production of “Dreamgirls.”

And yet, for all of its revealing detail, “Inventing David Geffen” is ultimately more about the business of Geffen than it is about Geffen the man. Propelled by a soundtrack of classic rock hits culled from Geffen’s peerless stable of artists, the film perhaps inevitably treats Geffen’s life and career as one and the same, with Geffen (through sheer chutzpah, destiny or a volatile combination of both) constantly at the epicenter of popular culture.

But aside from his generous philanthropy and political activism, we learn little about Geffen’s private life. He epitomized the American dream when he bought the palatial estate originally built and owned by legendary Hollywood mogul Jack Warner, but does he live there alone? Why don’t we see or hear about Geffen’s world-class art collection? How did he form his political views? What led Geffen to leave DreamWorks in 2008?

These are not minor omissions (and the turbulent history of DreamWorks is avoided altogether), but Geffen’s participation provides ample compensation. Using tidbits of interviews to punctuate a wealth of archival photos and footage, Lacy turns the sheer volume of talking heads to her advantage: Every facet of Geffen’s history comes with a well-matched observation from a film or music luminary, as when Young describes Geffen as “a performance artist, and the art of the deal is his stage.” In a clip from his Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame acceptance speech, Geffen himself provides the film’s most succinct appraisal of his spectacular success: “I have no talent except for the ability to enjoy and recognize it in others.”

It’s a genuinely modest statement, coming from that little kid from Brooklyn who imagined and then invented himself into Hollywood history.

Watch Inventing David Geffen: David Geffen In Three Words on PBS. See more from American Masters.

Watch Inventing David Geffen: ‘I’m in love with Cher!’ on PBS. See more from American Masters.