Whenever I am channel-hopping and happen upon “Singin’ in the Rain,” the classic MGM musical about the chaos that befell the film industry with the introduction of sound, two things inevitably happen. The first is that I pretty much stop everything else that I am doing in order to once again watch and delight in what is arguably the greatest movie musical of all time. The second is that I invariably begin thinking to myself “Man, that ‘Dancing Cavalier’ must have been one strange movie.” After all, if one is going to take a period costume drama/romance and add a bunch of musical numbers into the mix, especially something like the extended contemporary-set “Broadway Melody” number with Cyd Charisse vamping like nobody’s business, the results are almost inevitably going to be strange.

Of course, “The Dancing Cavalier” never existed, but if it did it would resemble “King of Jazz,” a crazy quilt of a film that arrived in theaters in 1930 with an avalanche of hype and one of the biggest budgets ever afforded a movie at the time, only to suffer catastrophic box-office failure. Now, after lingering in obscurity for decades, remembered mostly for marking the screen debut of a singer who would go on to become an enormous star, the film has undergone a massive restoration that has brought it back to its most complete form since it premiered. And, following a number of triumphant screenings at festivals around the world, is now making its DVD/Blu-ray debut as part of the Criterion Collection.

The “King of Jazz” in question was Paul Whiteman, a musical talent who was born in Denver in 1890, and who found himself playing viola for the Denver Symphony Orchestra at the age of 17 before conducting his own 12-piece musical outfit for the U.S. Navy in 1918. Following World War I, he formed the Paul Whiteman Orchestra in San Francisco, and, in 1920, the group moved to New York and began making records. While there has always been debate as to whether his music could properly be classified as jazz—it was more an amalgamation of jazz and traditional symphonic sounds that relied more on orchestrations and formal arrangements than on improvisation—the popularity of his sound could not be denied and he was soon making over a million dollars a year through live appearances while amassing 28 #1 records during the decade. At the same time that he proved to have an ear for what the audience wanted, he also demonstrated an eye for talent as well—he hired a number of the best jazz musicians of the era, including Bix Beiderbecke and Bunny Berrigan, and not only did he commission composer George Gershwin to write a piece that would become known as “Rhapsody in Blue,” his orchestra debuted it in 1924 with Gershwin himself at the piano.

Towards the end of the 1920s, the film industry was rocked by the arrival of sound via the mammoth success of “The Jazz Singer” in 1927 and when subsequent films proved that sound was more than just a mere novelty, the studios looked for way to take full advantage of the new process. Since it was now possible for music to become a key element of the filmmaking process, the studios began to look at singers and musicians as potential movie stars. With his huge success as a live act, the studios figured that the same audiences that flocked to see him in person would also turn out in droves to see him at their local movie theaters and began to pursue him aggressively. Eventually, Universal Pictures won out and signed Whiteman to a contract that was extraordinary advantageous for someone who had never stepped in front of a camera. For his services and the rights to his life story, Whiteman would receive 40% of the net profits with a guarantee of $200,000 and approval of both the screenplay and the director. (The studio would also pay the salaries of the 25 members of Whiteman’s orchestra for eight weeks of filming.) In theory, this may have seemed like an insane risk to take on an untested screen personality but with musicals now all the rage—Universal’s first one, “Melody of Love,” had been released ten days before the Whiteman signing and was doing brisk business—it seemed like a Whiteman project was pretty much a sure thing.

The first idea was to do a story based on Whiteman’s rise to fame with Whiteman and his band playing themselves. The one person who objected to this particular approach turned out to be Whiteman himself. Presumably recognizing his own limitations as a performer, he was not especially keen on doing anything that involved too much acting on his part and felt that he would be especially unconvincing as a romantic lead.

A second scenario was concocted that once again had Whiteman and his band playing themselves, this time in supporting roles in a kind of backstage musical comedy about an agent trying to convince a studio head to make a movie about Whiteman. Once again, Whiteman objected, this time on the grounds that the script made light of him and his band and, despite his reduced screen time, still gave him too much acting to do.

The whole production went on hiatus so that an acceptable premise could be found. By this time, the revue musical, a format that was simply a collection of individual acts without any overriding plot to speak of, had proven to be a success with the hit “The Hollywood Revue of 1929,” and it was decided that this approach would be the best way to go. After unsuccessfully trying to sign stage impresario Florenz Ziegfeld to direct “The King of Jazz,” Universal hired John Murray Anderson, who had done a number of successful revues on Broadway, to take charge, and the production, which had already incurred about $350,00 in costs without shooting a single frame of footage, finally got underway in October 1929.

The resulting film is essentially a grab bag consisting of selections from “Paul Whiteman’s Scrap Book” that will be brought to life for us through the magic of film. Things kick off with “A Fable in Jazz,” a short cartoon by a pre-Woody Woodpecker Walter Lantz that purportedly showed how Whiteman earned the title “King of Jazz” (while unsuccessfully hunting a lion in Africa, of course) and which is of historical note for being the first animation ever produced in Technicolor. There are large-scale production numbers like “My Bridal Veil,” which is essentially an extended fashion show showcasing bridal looks over the years and the Mexican set romantic interlude “Monterey.” There are also specialty dance acts like “My Ragamuffin Romeo,” in which Marion Stadler is hurled around the stage in astonishing ways by partner Don Rose and “Happy Feet,” an elaborate dance performed by German cabaret stars The Sisters G and the Russell Markert Dancers, before the group changed its name to the Radio City Rockettes.

“King of Jazz” feature a number of comedic bits: the humorous musical numbers like the backstage bit “The Property Man,” in which cabaret performer Jack White’s seemingly out-of-control performance is actually an incredible act of precision; a spoof of Universal’s other major production, “All Quiet on the Western Front” entitled “All Noisy on the Eastern Front”; blackout gags of the sort that used to kill time on stage between costume and set changes; a strange musical number that begins with musician Willie Hall playing “Pop Goes the Weasel” on a fiddle and ends with him playing “The Stars and Stripes Forever” on a bicycle pump. The sequence that tends to receive the most notice from contemporary viewers is a brief medley of songs by The Rhythm Boys, a singing trio that had been appearing with Whiteman’s band in concerts—this part is notable less for the singing, which is just fine, and more because it marks the screen debut of the soon-to-be-legendary Bing Crosby. (Crosby was supposed to be the featured singer in the additional number “The Song of the Dawn” but got into trouble with the cops just before filming and was replaced by fellow Rhythm Boy John Bole.)

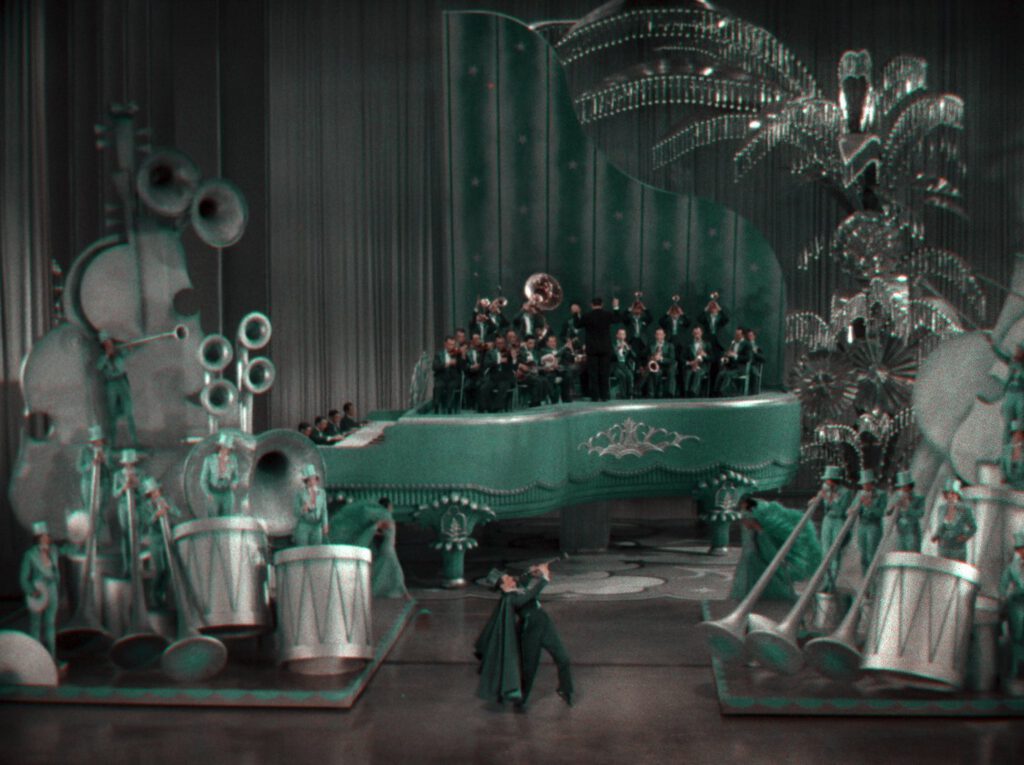

As for Whiteman himself, while he and his band can be heard throughout (Whiteman insisted on recording all the music before filming instead of playing live on the set, which was the custom in the early days of sound), his on-camera time is relatively brief. The centerpiece segment of the film is a nine-minute adaptation of “Rhapsody in Blue” featuring a production design centered around an enormous piano that the band plays atop of while the future Rockettes dance on the keys. (Contrary to rumor, the man playing the piano during this scene is Roy Bargy and not, as has been erroneously reported throughout the years, Gershwin himself.) In the grand finale, “The Melting Pot of Music,” Whiteman and the band attempt to illustrate all of the different sounds that contributed to what would become known as jazz by featuring individual songs and dances from Sweden, France, Italy, Ireland, Spain, Russia, Germany and Holland before bringing them all together for the big climax.

If you are looking at that list of countries that inspired jazz and thinking that something about it seems just a tad off, then you have taken notice of what is easily the most problematic aspect of the film—the fact that a movie entitled “King of Jazz” contains neither any acknowledgement of African contributions to the development of jazz music nor any black performers. (“Rhapsody in Blue” is preceded by an African-style dance number performed by Jacques Cartier, a white dancer wearing black lacquer.) To give Whiteman some credit, he would hire black musical arrangers and did what he could to encourage African-American musical talent, but the reality of the then-segregated times was that trying to play with black musicians could very easily destroy his career, and that attitude persisted when he made his jump to the screen. Seen today, these scenes now come across as questionable, to say the least. Cartier’s stylized dancing is striking, to be sure, but is at least partially undone by the knowledge that we are essentially watching a blackface routine. “The Melting Pot of Music” goes down a little better, if only because the total absence of African culture from a narrative about the development of jazz is such a blatant attempt at whitewashing history that it comes across more like a curiosity than something truly offensive.

When “King of Jazz” was released in May 1930, the reviews, by and large, were not especially kind—many dismissed it as just a random collection of elements that, while impressively stage from a technical standpoint, did not offer anything that set it apart from the numerous other revue films. Unfortunately for Universal, the public had also had more than their fill of revue films as well and wound up staying away in droves, essentially killing the musical as a viable genre until the smash success of “42nd Street” in 1933. Herman Rosse would win an Oscar for his stunning art direction, but the film would go down as a major flop, though it would have some success abroad in versions that were reedited to have homegrown stars introduce the various acts. When musicals came back into vogue in 1933, Universal recut it, deleting some scenes and adding others that had been cut from it before its original distribution, and rereleased it in America and while it did a little better the second time around, it would eventually fall into obscurity for decades.

As a straightforward moviegoing experience, “King of Jazz” is inevitably uneven. From a production standpoint, it is oftentimes stunning. Several of the numbers have been staged in such an elaborate and purely cinematic fashion that you never get the sense, as was sometimes the case with early musicals, that you are just watching a filmed show—the “Meet the Boys” sequence is an especially ingenious use of taking a favorite moment from Whiteman’s live performances and recalibrating it cinematically. The use of two-color Technicolor also leads to some striking effects, although the inability of the process to produce the color blue is a bit of a hindrance when it comes to the “Rhapsody in Blue” number. As for the performances themselves, some of them are still pretty impressive—the big “My Ragamuffin Romeo” and “Happy Feet” dance numbers showcase some killer moves from their performers and Jack White’s “The Property Man” number is a lot of fun. And while he is only on screen for a few minutes (though he can be heard on the soundtrack at a couple of other points, even in the opening cartoon), the star power of Bing Crosby was evident even at this early stage.

On the other hand, there are any number of problems with the film as well beyond the dubious racial aspects. For every lively bit, there is another one that just kind of lies there and does nothing. The worst offender by far has to be “My Bridal Veil,” a sequence that is undeniably impressive on a technical scale (it is probably the main reason why Rosse won his Oscar) but muddled from a narrative perspective. And it just seems to go on forever. Some of the comedy relief bits come up wanting as well—the quick blackout gags are little more than the film equivalent of a one-panel comic (one actually is an adaptation of a famous New Yorker cartoon) while the “All Noisy on the Eastern Front” sketch and the drunk act “Oh! Forevermore” elicit more shrugs than laughs. While the singers are all good, the baby voices utilized by some of them are more off-putting than adorable. As for Whiteman, his reticence about being front and center of a movie turns out to have been well-founded. Although a genial enough presence during his on-camera turns (which unfortunately makes the fat jokes aimed at him seem even crueler), whatever personal charisma he was able to generate on stage that made him such a popular star does not really come across well on film.

And yet, these complaints can be easily dismissed if one looks at “King of Jazz” less as a film and more as a time capsule of what was the rage in American popular entertainment around 1929-1930. Although it is not an adaptation of a specific show, the film does offer viewers at least some idea of what audiences could expect to see in a revue show from that era. There is a smorgasbord of talent on display here—singers, dancers, comedians, musicians and the like—and while Crosby is the only one that the average contemporary viewer might recognize, it is fascinating to see them all going through their paces at the peak of their powers. The enterprise as a whole is so odd, both in concept and execution, that even when it isn’t working per se, it still manages to evoke a strange but undeniable hold.

In fact, it is that very fascination that helped to keep the memory of the film alive for decades and would eventually lead to its restoration and revival. For decades, “King of Jazz” had essentially disappeared from view—no 16mm prints were made for non-theatrical outlets, it was neither reissued in theaters after 1934 nor was it included in the package of films Universal sold to television in 1957. While a cut-down version of the negative did exist, prints could not be made from it because the two-color Technicolor process it utilized was long obsolete. Over the years, however, bits and pieces were found and put together by archivists and a near-complete print of the film, rumored to have once been in the personal film collection of Benito Mussolini, was uncovered in the late ‘60s. In the ‘80s, a version of the film cobbled together from both the 1930 and 1933 editions was released to cable and home video by MCA Universal, who pushed Crosby as its star despite his relatively brief screen time. Never released on DVD, this version would fall into obscurity as well once VHS faded from view. In 2002, an 83-minute nitrate print of the film was found in a shipment of crates of titles owned by late collector Raymond Rohauer that were sent to the Library of Congress. In 2010, NBCUniversal spearheaded a major restoration of the film utilizing this print and elements cobbled together from other sources (with still photos used to represent the few moments that simply could not be found) to recreate the version of the film that audiences saw in 1930. (The story of this restoration is recounted in much greater detail in King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, James Layton and David Pierce’s book chronicling the entire history of the film and its key participants.)

While the restoration of “King of Jazz” alone would have been enough to make this Blu-ray a must-own for students of American film, stage and pop culture history, Criterion has gone the extra mile with a slew of exceptional special features that help give greater context to the film. Music/film critic Gary Giddins offers an introduction to the film and is joined by cultural critic Gene Seymour and bandleader Vince Giordano for an informative commentary tackling the history of both the movie and Whiteman himself. Layton and Pierce contribute four visual essays chronicling the film’s history and additional insight is offered up in an interview with musician Michael Feinstein. The scenes added for the 1933 reissue are included here as well as an alternate opening title sequence. There are also a number of vintage shorts on hand as well, including “All Americans,” a 1929 effort featuring a different version of the “Melting Pot” number, a couple of 1930 cartoons from Walter Lantz featuring Oswald the Lucky Rabbit that include material taken from the film’s cartoon sequence and “I Know Everybody and Everybody’s Racket,” an odd but fascinating 1933 comedy short featuring infamous Broadway columnist Walter Winchell playing himself, here squiring a seemingly innocent young lass around the streets of New York on an evening jaunt that includes a stop to see Whiteman and his orchestra playing. Throw in an informative essay from film critic Farran Smith Nehme and you have one what will surely go down as one of the best Blu-ray releases of a vintage film to come along this year and one that will hopefully return “King of Jazz” to the rightful place in the history of early sound film that it so richly deserves.

(“King of Jazz” is now available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.)