I was floored by Tomas Alfredson‘s “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” the first time I saw it, though (as is usually the case for me, even with movies that don’t negotiate complex plots in slyly evasive/elliptical styles), I couldn’t have told you exactly what happened. That didn’t concern me at all, however, because like its central character George Smiley (Gary Oldman), the movie is so meticulously observant that I never felt I was missing out on anything important, even when I wasn’t sure exactly what was going on. It kept me in the emotional moment, and I knew I could figure out the details later on.

The stories behind the relationships at the Circus (nickname for Britain’s covert intelligence agency) were tangled — and yet clearly delineated — enough to deliver a cumulative emotional payoff. And the more I lived with the vivid memory of the movie (it has stayed with me, unshakably), and the more times I’ve seen it (thrice, so far), the more my appreciation of it has grown. It has slowly climbed up my list of 2011 favorites, and by the second time I saw it, I was absolutely sure it had eclipsed any other English-language movie I’d seen during the year.

(For gaffe squadders who enjoy those fits of righteous indignation that only award nominations can truly provide, let me suggest that the most egregious oversight in this year’s Oscar batch is the lack of acknowledgment for “Tinker Tailor” in the categories of best picture, supporting actor (anyone), supporting actress (Kathy Burke), cinematography, art direction, editing, costume design, and so on down the line. Screenplay, actor and music — all well-deserved, though.)

First-rate movies often inspire first-rate criticism, and it’s been thrilling to read some of the year’s best writing inspired by one of its best movies. Here’s a sample of some of the finest stuff I’ve read (all of it after I saw, and wrote a little about, the movie — so beware of spoilers), with links to the full pieces, which I strongly recommend you follow.

Kathleen Murphy, “Darkness Shines,” MSN Movies:

Coolly pursuing intelligence, Alfredson’s camera eye inches slowly toward window after window, to frame spooks looking out, as though thirsty for some clue that might complete and revivify the existential jigsaw puzzle in which they’re trapped. “Let the Right One In” began with a lonely child perched at a window, spying on other, seemingly happier lives across the courtyard, each apartment a movie screen for a boy with hungry eyes. Similarly, Circus thug Ricki Tarr (Tom Hardy) surveils three windows across from his hotel, witnessing infidelity and a wife’s bloody beating. Tarr’s Peeping Tom, blinded by a damsel in distress, blows his cover to take a leap of faith. In these cold climes, love is always a fatal fall. Even Smiley can’t “see straight” for doting on wife Ann, his “Achilles’ heel.”

There’s no emotional exit in these Escher-like environs, no real “outside” or locus of everyday life, nothing beyond the Circus, despite mindless commitment to winning the Cold War for an abstraction called the West. Everyone’s a permanent insider, encoffined in shabby offices and dim apartments, sky-blocking edifices, even a claustrophobic camper. […]

No one in “Tinker Tailor”‘s cast, a pantheon of British heavy-hitters, sets a foot wrong. Firth manages, masterfully, to thin his omnivorous charm and good looks, exposing terrifying emptiness beneath. Mark Strong especially surprises, leaving recent cartoon-villain roles behind to deliver a nuanced, heartbreaking performance as another spy who, ensorcelled by a smile, tries to come in from the cold.

But it’s Oldman whom Oscar should reward. A clenched soul hunkered down behind a worn mask, scoured of affect, Oldman’s Smiley turns his head like a gun turret, black-hole eyes absorbing data and pain. Emotion leaks out of that carapace just three times: when he spies his wife’s infidelity; in exasperated contempt for a colleague’s shallow treachery; and most terribly, during a long monologue in which he recounts, in devastating closeup, a long-ago meeting with Russian counterpart Karla, when the soul-killing pointlessness of life in the Circus hits home. The hollow man’s mask decomposes, Nosferatu blasted by sunlight.

Richard T. Jameson, “Top 10 Movies of 2001: No. 5,” MSN Movies:

Early in “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy,” veteran cold warrior and abruptly retired spy George Smiley (Gary Oldman, magnificent) stares across his sitting room at a painting. The screen is vast, the painting tiny; we can make out only a pattern of frames within frames, one of them as red as a wound. Director Tomas Alfredson ‘s credit appears over the shot, making it seem a mite insistent as an abstraction of impenetrably enigmatic John le Carré world and an assertion of stylistic principle. The movie often has us watching people watching through frames — windows, doorways, ironwork — and being themselves watched; sometimes they furtively cherish the mutual recognition. Yet Alfredson’s signature shot isn’t just a viewing instruction. Much later we’ll learn how that painting (which we never do properly see) entered Smiley’s life, and what an array of meanings and losses it indexes for him. And please note that we learn this only in passing, almost literally as a throwaway, while following the byzantine course of the larger story about the search for a Russian mole in the highest circle of British intelligence. “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” isn’t everyone’s choice as best movie of the year, but none has been better made.

David Bordwell, “TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed, Observations on film art:

[This piece goes into splendid detail about the film’s distinctive 1970s look, its elliptical approach to narrative and its vision of the characters, particularly Gary Oldman’s George Smiley, using comparisons to the novel and the 1979 BBC mini-series with Alec Guinness.]

Critics of popular filmmaking claim that our movies cater to simple minds, but we actually find a lot of successful films, from “Groundhog Day” and “Pulp Fiction” to “Inception,” that are complex in intriguing ways. I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It that since the 1960s one current of filmmaking has explored narrative strategies that were minor, even unheard-of, options in earlier times.

I’m not ready to join Steven Johnson in suggesting that audiences have become smarter. In certain respects older films are more demanding than contemporary ones. I’d rather say that new conventions are in force, aimed at certain sectors of the audience who are willing to put forth the effort. Ambitious filmmakers may find new ways to fulfill these conventions, balancing novelty with intelligibility. This is the path, I think, that the makers of “Tinker Tailor” took, and it didn’t prevent the film from earning $17 million at the US box office.

The film’s ’70s patina isn’t off-putting. The filmmakers offer deliberately grainy imagery, enveloped in hazes of rain and cigarette smoke. The palette, except for Ricki Tarr’s idyll with Irina, is grey, brown, and beige. Scenes are shot with long lenses, rack-focus, and drifting tracking shots. Zooms and push-ins are interrupted by cutaways. The result is an Altmanesque look, but more disciplined. It’s not the visual style, then, but those the narrative pretzels–another reminder of late ’60s and early ’70s storytelling — that attract my notice today. […]

Above all are the eyeglasses. Promoted in the film’s publicity (when Oldman found them, he found the character), they become associated with seeing things as they are. The old hornrims seem to be something of a shield; Smiley pushes them back into place after he sees Bill with Ann. But once Smiley has gotten his new, more powerful pair after leaving the Circus, he uses them as an instrument of scrutiny. They enlarge his vision eerily; often they’re lit and in focus when his eyes aren’t. And they hide his eyes from others. […]

By contrast [with Guinness], as every critic has noted, Oldman’s Smiley is virtually blank for most of the film. His frog-mouth, half-open or clamped shut, remains impassive. Guinness lets us into Smiley’s mind as he interrogates his targets, but Oldman’s most marked reactions are brow-wrinkling concentration and puzzlement. The high point, George’s discovery of Ann’s disloyalty, elicits only a gasp and a gape (and a pushing up of the glasses). As usual, even that reaction is muffled a bit, this time by the profile angle.

Similarly, everything conspires to make George obscure. Framing, setting, and lighting put him far from us, wrap him in shadows, let reflections on his spectacles block his eyes.

Guinness’s Smiley isn’t hard to read, once you tune to his high, narrow frequency, but Oldman’s Smiley is a sphinx. And it seems to me that this poker face works toward a new conception of Smiley’s role. The elliptical narration conspires with Oldman’s performance to create a conclusion that is far more harsh than what we find in the book or the series.

Early on, the film shows us George shamed. Control, forced to resign, announces that Smiley will leave with him. It evidently comes as a surprise to Smiley, who — in a moment that many critics have rightly praised — turns his head slightly and after a beat and a blink accepts with a tiny nod. For the rest of the film, George’s head-turns will be his principal signal of surprise, uncertainty, or sudden realization. (It’s even contagious: his adversaries execute the same gesture, and even Guillam catches the habit.) Smiley and Control stalk out of the Circus as exiles and part on the sidewalk without a word and Smiley comes home to an empty house.

Jason Bellamy, “Loner Lover,” The Cooler:

Guns are fired in Alfredson’s film, but there are no shootouts. Punches are thrown, but there are no fight scenes. Pursuit of the enemy is a constant, but there are no chase sequences. Somehow the movie is still outwardly slower than what I just described, and yet it challenges us to match its pace. Just beyond its calm demeanor and passive posture, “Tinker Tailor” is a maelstrom of information — clues dropped without fanfare, all of them exposing hidden truths that point to the identity of the mole and then to even deeper personal truths beyond that. Those who have read the novel or watched the 1979 miniseries starring Alec Guiness will have an easier time staying afloat. But the rest of us have no choice but to splash around in the torrent of first names, last names, codenames, nods, glances and insinuations while trying to keep our heads above water.

The first time I watched “Tinker Tailor,” I followed it well enough, but it took a second viewing to really feel it. There’s no shame in that, nor is there fault to be found in the film’s deliberate avoidance of boldface elucidation. Alfredson’s adaptation is a reflection of the film’s main character, George Smiley, the externally unhurried former agent of the British Secret Intelligence Service who goes searching for a mole inside the “Circus” as a storm of doubts, regrets and suspicions thunders inside him. At the same time, “Tinker Tailor” puts us in touch with Smiley’s experience, giving us a palpable sense of, and a great respect for, the tangled web of information that he must unravel to uncover the truth. Smiley is never spoon-fed, and thus we aren’t either, and no matter how many clues pass before us, Smiley is always one step ahead, deciphering the significance of the seemingly trivial. Thus, we often spot that Smiley has had an epiphany long before we have one of our own. The complexities of the plot are reason enough to see the movie (at least) twice, but there’s also this: Among other things, “Tinker Tailor” is actually about the act of reexamination, the discovery of new details through a second look at the familiar.

Bilge Ebiri, “The Ghost in the Machine,” They live by night:

I’ve watched Tomas Alfredson’s “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” twice now and I’m still not sure I understand all of it. The story, at least in its broad strokes, is fairly simple, but structurally it burrows into little pockets that are sometimes hard to untangle. The film moves not like a river but an octopus at the bottom of the sea; you sense the overall form sliding along, but you can’t always follow the individual tentacles. And yet, I can’t tear myself away from it. […]

“Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” uses mood the way other movies might use plot points. Into this impeccably crafted recreation of a dry, drab, smoky bureaucracy, Alfredson carefully allows sharp little pangs of emotion: A jealous glance, a furtive embrace, a barely-glimpsed and hasty goodbye between two lovers. Maybe that’s why the film always feels like it’s ending. It’s shot in this persistent, autumnal glaze that makes everything seem like the last act of something, which is perhaps the ideal way to make a movie about people hiding very important things.

I haven’t read le Carre’s novel, but the filmmakers have spoken elsewhere, briefly, about their own addition of homosexuality into the film. But they’ve added it in such a glancing manner that you could easily miss it — in fact, even as I write these words I’m not 100% sure to what extent the element is there, particularly at the end. But that very uncertainty seems to be part of the film’s design. It’s amazing how often we’ll catch a glimpse of a body in the film, without ever seeing the face. Like there’s a story not quite being told hovering on the edges of the frame, constantly fleeing from our judgmental glance. We’re never getting the whole story.

Lance Mannion, “Tinker… tailor… soldier…:

But being taken for granted, getting overlooked, having people forget he is there even while they’re looking right at him are among his chief skills as a spy. He is an expert at fading into the background. He’s there, but not there, seen but not really seen. You look at him and you can’t quite pick him out from the scenery. He’s deliberately blurry.

That’s what Oldman emphasizes, Smiley’s uncanny ability to take himself out of focus.

Oldman is constantly looking away, leaning back, turning his back on other characters and to the camera, and wandering off towards the edge of the frame. Actors are taught from the beginning of their training to “find their light.” Oldman finds his shadows.

In one of Oldman’s best scenes, Smiley recounts for his young assistant the time twenty years before when he met and interrogated Karla, Smiley’s Soviet counterpart and the spymaster assumed to be running the mole. The recounting turns into a re-enactment, with Smiley taking on both parts, and as he gets into it, Oldman seems to wrap band after band of shadow around himself, blanking out more and more of himself until there are only jagged bits and pieces of himself left in any light at all. This is where Smiley likes to work, in the near dark. It’s also how he works. So we’re not surprised to learn that while Smiley remembers Karla vividly, Karla remembers only one thing about Smiley. It happens to be a very important and damaging thing and a blow to Smiley’s pride. Guinness let us see that pride. Oldman lets us see it as he swallows it.

When he’s forced into the light and has to let others see him full on, Oldman’s face, his whole body, go perfectly still. There’s not a twitch of a lip, not the barest raising of an eyebrow, not the slightest shrug to give even the keenest observer a clue to his thoughts or his feelings. All there is to go on are his eyes, huge behind those glasses, wide-open, taking everything in. […]

The stand-out [in the supporting cast], though, is Mark Strong, as the “scalphunter” Jim Prideaux, the one real secret agent in the group — that is, the one who, after Smiley, has come closest to leading an actually heroic life — who against his better judgment takes on one last assignment, ostensibly to get the name of the mole, but in his own mind hoping not to be told. Prideaux becomes one of the mole’s victims. He gets shot, he gets tortured, he gets shown the door when he’s finally returned home in an exchange with the Soviets that results in the deaths of several of Prideaux’s “assests.” But none of that leaves as deep or as painful a mark on him as knowing he’s been betrayed and who by. As Smiley, Oldman allows his eyes to reveal nothing. They take everything in and let nothing out. As Prideaux, Strong’s eyes reveal only one thing, heartbreak, and they let it all out.

Peter Straughan, co-screenwriter:

Working with Tomas [Alfredson] was a little like working on a project with a mad professor. Instead of the usual studio notes on “characters arcs,” “three-act structure,” and “dramatic stakes,” Tomas would begin a script meeting by wondering what kind of fairy story “Tinker Tailor” would be; the good Prince who is thrown out of the castle and must defeat the usurper King, we decided. Another meeting began with Tomas arriving with a chess set he had just bought. Which character was which piece, he wondered? We spent the afternoon playing with that idea — and the chess pieces made it into the script. Other notes included his telling the cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema that the film should look like the smell of wet tweed. (He told me that world should have the color of an old man’s foreskin. I haven’t actually seen an old man’s foreskin, but I took the point.) […]

The adaptation process differs from book to book, but in the case of “Tinker Tailor,” it involved a kind of mosaic work. The structure of the novel was broken into pieces. Some long sequences would remain intact — Peter Guillam stealing the files from the Circus, for example — but in other cases we would take a line or event from one place in the narrative and move it elsewhere, shifting the fragments around endlessly until it felt right. The goal was to create a new version of the narrative which would bear a close family resemblance to the source material, but have its own cinematic personality. The really difficult part was not fitting the plot into two hours but doing it without losing the tone; to give the film the same autumnal, melancholy pace, and to give the script air and silence.

As the drafts progressed it became evident where new sequences, scenes and images would have to be injected. Bridget, who was endlessly inventive, came up with many of these ideas — from Guillam’s homosexuality to the new café scene at the opening to the simple but eloquent image of Smiley swimming in the ponds at Hampstead Heath, looking at the trembling elderly bodies around him and wondering if this was his world now.

Director Tomas Alfredson, “George Smiley’s glasses are key to ‘Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy’,” The Envelope (Los Angeles Times):

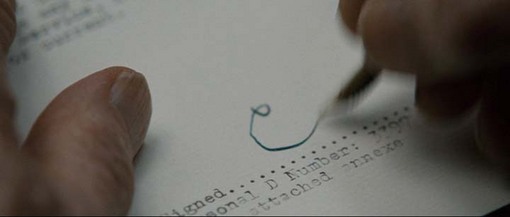

“If you have a main character who will be onscreen for 80% of the film, if you put something on the middle of that person’s face, it will be in each and every shot,” Alfredson explained. “In many ways it could be more important than cars, sets and constructions.”

In addition to helping guide the audience, the glasses were also a critical component in constructing the character. “Smiley is a voyeur, he almost doesn’t speak in the film, it’s a very quiet part,” Alfredson added. “So his eyes are extremely important and they are very active in what they are reflecting.”

Alfredson, Oldman and costume designer Jacqueline Durran spent hours discussing exactly what Smiley’s first and second pair of glasses should look like.

For the first pair, Alfredson said that “Smiley is described as someone you would immediately forget. For that reason, we were looking for things that would make him as anonymous as possible. We decided not to put cufflinks on him — he would have a very gray and anonymous suit, white shirts. No details that people would remember. And his old glasses, we thought, should be the kind of glasses you were given in the military service. They’re very anonymous too.

“And with the new glasses, we wanted something that was more contemporary and we wanted them to have a lot of surface so they would reflect what was in the room in front of George,” Alfredson said. “Usually, you have this coating on glasses when you do films because you don’t want reflections, but in our case, we wanted reflections.”