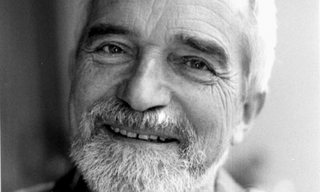

I was in high school when I picked up a hardback copy of the first edition of Robin Wood’s “Hitchcock’s Films” (1965) from a remainder table at a depressingly small, sterile, fluorescent-lit Crown Books in an old-fashioned, long-gone outdoor mall (called Aurora Village) in North Seattle. That was in the mid-1970s and now I’m writing this and Robin Wood died last week at the age of 78.

I’ll never forget standing in that store, reading the famous, much-quoted opening words:

Why should we take Hitchcock seriously?

It is a pity the question has to be raised: if the cinema were truly regarded as an autonomous art, not as a mere adjunct of the novel or the drama — if we were able yet to see films instead of mentally reducing them to literature — it would be unnecessary.

(David Hudson, in his round-up of tributes to Wood, reproduces part of the first page at The Auteurs Daily.)

The forces that necessitate the question Wood asks — not just about Hitchcock but about all movies — are still in place today, though not as monolithically as they were when Wood wrote those words. My friends and film professors fought that attitude all the time when I was in college, it was so prevalent among students, faculty and the general public.

And it still is today. Try to talk about movies as movies — that is, as Wood said, as a unique art form and not an outgrowth of literature or theater — and somebody will think you’re getting too “technical” (as happened at a recent year-end critics’ panel I participated on at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle). Kathleen Murphy responded: Would it be too technical to discuss the texture and color of paint on a canvas? Well, of course not. But may people still view movies as little more than stories told with actors, rather than, say, considering shots as sentences — with shapes, contours, rhythms, colors, nouns, verbs, adjectives…

I’d read movie reviews since I was a kid (John Hartl in the Seattle Times, Paul Zimmerman in Newsweek, eventually Pauline Kael in The New Yorker…) but Wood’s Hitchcock book was the first thing of its kind I’d ever encountered — though I also came to treasure his book on Howard Hawks and his collections of essays (“Personal Views” and “Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan,” especially). He loved Mizoguchi’s “Sansho Dayu” and Ophuls’ “Letter From and Unknown Woman” as much as I did, and wrote deeply and poetically about them. Later, I thought he misunderstood Cronenberg (he detected a revulsion for all things fleshly), but he was still more engaged with the actual work than just about anybody else at the time. (Like many great critics, he could be incredibly perceptive, even when you thought his eventual judgements were off-base.)

Charles Barr wrote in The Guardian:

Before he published “Hitchcock’s Films” in 1965, there were — in English, as opposed to French — virtually no books on film directors, and few books of any kind that brought either rigour or sympathy to the analysis of popular cinema. The teaching of so-called “film appreciation” in Britain was confined mainly to a few pockets within adult education and teacher training. This was already starting to change, but Wood’s work was a key influence in validating and shaping a new discipline.

And, of course, Hitchcock — whose attention to composition and cutting are so precise — offers the perfect introductory opportunity for a master class in how movies work. Wood put it all together.

David Bordwell offers the most moving and insightful of the Wood appreciations I’ve read:

I can’t convey the excitement that was ignited by “Hitchcock’s Films” (1965), “Howard Hawks” (1968), and “Ingmar Bergman” (1969), quickly followed by the monographs on Penn (1970) and Ray’s Apu Trilogy (1971). Nearly all books of film criticism were then simply collections of reviews. Wood’s stood as through-written, pondered over, carefully carpentered books, comparable to the best literary analysis. These monographs showed, in incisive detail, what most auteur criticism simply proclaimed: great directors expressed their personal vision of life in and through cinema. Wood showed, scene by scene and sometimes shot by shot, that movies harbored layers of feeling and implication in their finest grain of detail. Without fanfare he introduced “close reading” to film criticism.

DB quotes a paragraph from Wood’s “Rio Bravo” essay (Jonathan Rosenbaum reports that Wood recalled Hawks’ great western on his deathbed as his favorite film, along with “Sansho Dayu,” “Tokyo Story,” “Letter From an Unknown Woman,” “Le Crime de Monsieur Lange” and some surprises), which he describes as “a sort of draft for what would become one of his most important statements”:

Wood: Hawks, like Shakespeare, is an artist earning his living in a popular, commercialized medium, producing work for the most diverse audiences in a wide variety of genres. Those who complain that he “compromises” by including “comic relief” and songs in “Rio Bravo” call to mind the eighteenth century critics who saw Shakespeare’s clowns as mere vulgar irrelevancies stuck in to please the “ignorant” masses. Had they been contemporaries of the first Elizabeth, they would doubtless have preferred Sir Philip Sydney (analogous evaluations are made quarterly in Sight and Sound). Hawks, like Shakespeare, uses his clowns and his songs for fundamentally serious purposes, integrating them in the thematic structure. His acceptance of the underlying conventions gives “Rio Bravo,” like Shakespeare’s plays, the timeless, universal quality of myth or fable.

I’m grateful to Wood for so much. As he must have been comforted and strengthened by recalling “Rio Bravo” in his final hours, I’m consoled and inspired by this, from Barr’s obit:

The opening of Wood’s last book, a study of the Howard Hawks western “Rio Bravo,” published by the BFI in 2003, is typical of his insistently personal style, and of the intensity with which he lived movies, as he did so much else. It describes how, being rushed to hospital in an earlier medical crisis, he found real serenity of mind in thinking about the stoicism with which Hawks’s characters habitually encounter death.

So long, Robin Wood. You were one of the best…

* * * *

Extensive Wood resources: Crossing the Wild River: R.I.P. Robin Wood (1931-2009), Catherine Grant’s Film Studies For Free

A Life in Film Criticism: Robin Wood at 75, Your Flesh Magazine.

A Robin Wood Bibliography compiled by D.K. Holm.

UPDATE: Just discovered that Dennis Cozzalio at Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule has a characteristically fine piece on Wood, “Rio Bravo” and “High Noon” that helps to combat the ignorance of a showbiz gossip blogger who shall go unnamed. And Dennis uses the same image-grab I kiped for the top of his piece!