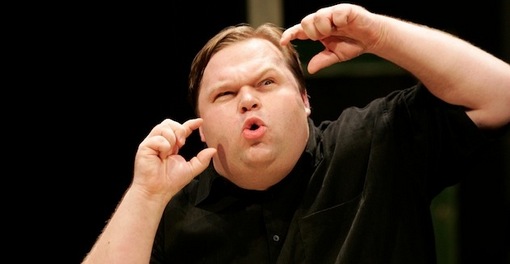

My uneasiness about the relationship between Mike Daisey‘s theatrical piece “The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs” and its presentation as journalism on This American Life centers on three things. The first has to do with the art of storytelling. Daisey is a performer and storyteller who combines personal anecdotes, fiction and fact, into stage monologues. Nothing wrong with that; it’s what monologists do. The second has to do with journalism. This American Life, the Chicago Public Radio/PRI show, also focuses on storytelling — often personal stories — but expects them to meet the factual standards of journalism, unless otherwise noted. As host Ira Glass said in the show’s most recent episode, retracting the earlier one called “Mr Daisey and the Apple Factory“: “Although [Daisey is] not a journalist, we made clear to him that anything that he was going to say on our program would have to live up to journalistic standards. He had to be truthful. And he lied to us.”

And the third, and probably the most troublesome aspect for me, has to do with the media’s definition of “the story” itself, which has focused on details about Apple (because it makes a better story to connect the shiny new iPad or iPhone to cheap Chinese labor), even though Apple is just one of many major corporate customers of Foxconn, the company that runs the factories. Some very good reporting has been done on the subject (by Charles Duhigg and David Barboza in the New York Times and various reporters at CNN and NPR, just to name a few). But the hook is always Apple. And while I have no reason to believe the reporting is untrue, the framing of the story can be misleading.

So, let’s try for a little perspective: The exploitation of factory workers overseas is much bigger than Apple products. It’s bigger than Foxconn. It’s bigger than electronics. And it’s bigger than China. Yes, you need specific, factually verifiable information to validate journalism, and to get your audience to care about your story. That’s where the “storytelling” comes in. But all it takes is a quick look at, say, Foxconn’s Wikipedia page and you’ll find sourced links showing that the company is a Taiwan-based multinational, with operations not only in China (where it is the largest private sector employer) but in Brazil, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, India, Malaysia and Mexico. Among the non-Apple products it manufactures and/or assembles: the Xbox 360, the PlayStation 3, the Wii, the Kindle and various phones, televisions and other devices. And its largest customers also include Acer, Amazon, Cisco, Dell, HP, Intel, Microsoft, Motorola, Nintendo, Nokia, Samsung, Sony, Toshiba and Vizio. That’s just one company (Foxconn) and one industry (consumer electronics).

We’ve often discussed how movies (documentaries as well as fictionalized features that profess to be “based on” (or “inspired by”) “true stories) select, adapt and shape the stories they tell. Journalism can’t help but do the same thing, but the goal of reporting (unless it’s ideologically motivated, like Pravda or Fox News or MSNBC or Michael Moore) is to factual accuracy, while art and entertainment put a greater emphasis on beguiling storytelling, even if that involves changing the truth. (Joel & Ethan Coen made a joke of this by beginning “Fargo” with a claim that it was a “true story,” when it was no such thing.)

Daisey and Ira Glass have this exchange on the retraction show:

Mike Daisey I am agreeing it is not up to the standards of journalism. And that’s why it was completely wrong for me to have it on your show. And that’s something I deeply regret. And I regret that the people who are listening, the audience of This American Life, who know that it is a journalistic enterprise — if they feel misled or betrayed, I regret to them as well.

Ira Glass Right, but you’re saying that the only way that you can get through emotionally to people is to mess around with the facts. But that isn’t so.

Mike Daisey I’m not saying that that’s the only way to get through to people emotionally. I’m just saying that this piece, in how it was built for the theater, follows those rules. I’m not saying it’s the only way to do things.

Daisey’s apology is fine, as far as it goes. It doesn’t address his deliberate lies when asked directly about certain incidents, or his efforts to keep the TAL fact-checkers from contacting his Chinese translator, but I’m sympathetic to the differences between art (including activist art) and journalism.

A bigger problem, I think, is in how Glass introduced Daisey and his work in the original piece TAL aired in January:

A couple weeks ago, I saw this one-man show where this guy did something onstage I thought was really kind of amazing. He took this fact that we all already know, this fact that our stuff is made overseas in maybe not the greatest working conditions, and he made the audience actually feel something about that fact. Which is really quite a trick. You really have to know how to tell a story to be able to pull something like that off.

And I bring this up because today we are excerpting that story here on the radio show. The guy’s name is Mike Daisey, and he makes his living doing monologues on stage. He’s been doing that for years, though you’re going to hear, in this story, that he turns himself into an amateur reporter during the course of the story, using some investigative techniques, once he gets going, I think, very few reporters would ever try, and finding lots of stuff I hadn’t heard or seen anywhere else. Not like this.

Glass takes the performance he saw on stage and then claims that Daisey became “an amateur reporter” using “investigative techniques” in order to tell his story. So, he set up his audience to believe that Daisey’s stage piece was factually corroborated. And it wasn’t. Journalism, like science, is a process, with rules and restrictions designed to yield a reliable, verifiable result (even though it doesn’t always turn out that way, especially when people lie). The trouble is that TAL‘s story relied on Daisey not just as its reporter but as its primary source, and left little wiggle room for the “larger truth of art” because Glass expected it to pass journalistic muster. Sure, we’ve heard elsewhere about manufacturing, hazardous conditions and worker abuse in China, but Daisey was presenting specific incidents and encounters as if he had witnessed them himself, and TAL was casting him as an “amateur reporter.” Now, I’ve heard a lot of first-person stories on TAL, and I don’t know how many of them I’d believe were 100 percent factual. (To quote Artie, Rip Torn’s character on “The Larry Sanders Show”: “Don’t start pulling at that thread or your whole world will unravel.”) Was I supposed to? Because they weren’t set up as journalistic stories.

I wonder if Ira Glass is playing a fictionalized version of himself in this exchange with NYT reporter Charles Duhigg in Part 3 of the Retraction show. Does he really not understand the role of a journalist, or is he just acting out this part for the benefit of his audience?

Ira Glass To get to the normative question that’s kind of underlying all the reporting and all the discussion of this, the thing that we all want to know when we hear this is, like, wait, should I feel bad about this? You know what I mean? As somebody who owns these products, should I feel bad? And I don’t know that I feel so bad when I hear this.

Charles Duhigg So it’s not my job to tell you whether you should feel bad or not, right? I’m a reporter for The New York Times. My job is to find facts and essentially let you make a decision on your own. Let me pose the argument that people have posed to me about why you should feel bad, and you can make of it what you will.

And that argument is — there were times in this nation when we had harsh working conditions as part of our economic development. We decided as a nation that that was unacceptable. We passed laws in order to prevent those harsh working conditions from ever being inflicted on American workers again.

And what has happened today is that, rather than exporting that standard of life, which is within our capacity to do, we have exported harsh working conditions to another nation. So should you feel bad that someone is working 12 to 24 hours a day in order to produce the iPhone that you’re carrying in your pocket —

Ira Glass Well, when you say it like that, suddenly I feel bad again. But OK, yeah.

Charles Duhigg I don’t know whether you should feel bad, right?

I find that (faux?) naïvete (“Tell me what to feel!”) a little exasperating. (What’s more germane is that Duhigg says, even at current iPhone prices, at which Apple makes “hundreds” of dollars profit per phone, producing them with American labor would only add $65 to the cost of each handset. Apple wouldn’t even have to raise the price and it would still make a handsome profit. But the availability of labor isn’t just about cost, it’s about speed and flexibility. Duhigg says Foxconn is centralized and set up to adapt to manufacturing changes and demands in hours instead of days or weeks. Again, though, in this TAL segment, the focus is all on Apple, not any of its competitors who also use the same company’s factories.)

NYU journalism professor Jay Rosen gets to the heart of the matter, I think — and its something Glass all but acknowledges in his original intro:

This American Life is about stories. No word is more basic to the show than that… “story.” You could almost say that the show fetishizes the “story” as object. I think Ira Glass could have dug a little deeper into why he and his team made that fatal error and broadcast the segment even though they could not fully check it with the translator. They could have adopted as a working hypothesis that such an error was years in the making, not an isolated slip-up but something that cut deeper. If they had done that, they might have begun to question whether it is possible to fall too deeply in love with “stories” and their magical effects; whether that kind of love erodes skepticism, even when you are telling yourself to be skeptical; whether Ira and his colleagues in some way wanted Daisey’s stories to be 100 percent true, whether this wish interfered with their judgment, whether there isn’t something just a little too cultish about the cult of “the story” on This American Life.

Well, TAL is theater — it’s constructed and presented as radio theater. Personally, I’ve never thought of it as journalism. As a former reporter, I don’t see how it could be — it’s too reliant on first-person storytelling that in many cases can’t be fact-checked because it relies too much on childhood memories or eyewitness recollections or other subjective, unreliable and ephemeral sources. The stories often involve the participants’ varying/conflicting accounts of what happened. Any reporter knows that people are going to tell you their reality (the one they believe or the one they want you to believe — and sometimes those intersect), but there isn’t always a way to document or externally verify their stories.

The borders between fact, fiction and what Daisey calls the “larger truth” is a treacherous one, crossed or blurred at your own peril — unless you’re up-front about what you’re doing. First-person monologues are subjective by nature. Nobody expects that story about your family Christmas when you were seven to be absolutely, verifiably true — and to align completely with the memories of everyone else who was there. That’s not the point. Here’s a scene from “The Agony and the Ecstasy of Steve Jobs,” excerpted in the TAL story, “Mr. Daisey and the Apple Factory“:

I talk to an older man with leathery skin. His right hand is twisted up into a claw. It was crushed in a metal press at Foxconn. He says he didn’t receive any medical attention, and it healed this way. And then when he was too slow, they fired him. Today he works at a woodworking plant. He says he likes it better. He says the people are nicer, and the hours are more reasonable. He works about 70 hours a week.

And I ask him what he did when he was at Foxconn. And he says, he worked on the metal enclosures for the laptops, and he worked on the iPad. And when he says this, I reach into my satchel, and I take out my iPad. And when he sees it, his eyes widen. Because one of the ultimate ironies of globalism — at this point, there are no iPads in China. Even though every last one of them was made at factories in China, they’ve all been packaged up in perfectly minimalist Apple packaging, and then shipped across the sea so that we can all enjoy them.

He’s never actually seen one on, this thing that took his hand. I turn it on, unlock the screen, and pass it to him. He takes it. The icons flare into view. And he strokes the screen with his ruined hand, and the icons slide back and forth. And he says something to Kathy. And Kathy says, “He says it’s a kind of magic.”

Rob Schmitz, the Shanghai-based Marketplace reporter who tracked down Daisey’s translator, Cathy Lee, asked her about the incident:

Cathy No. This is not true. It’s just like movie scenery.

Rob Schmitz It sounds like a movie?

Cathy Yeah.

Rob Schmitz Yeah, yeah.

Cathy Very emotional. But not true to me.

But later, Cathy says: “He’s a writer. So I know what he says, maybe only half of them or less are true. But he’s allowed to do that, right? Because he’s not a journalist.”

No, but he apparently played one — if not onstage, then on the radio.

P.S. Steve Myers and Craig Silverman at Poynter.org have a list of questions about TAL and journalism that they’d still like answered:

☛ What specifically is the fact-checking process at “This American Life”? Does this apply to all stories? If not, which ones?

☛ As this show was being produced, did the staff have an opportunity to raise concerns about the reliability of Daisey’s account? Would their input have mattered?

☛ Besides the decision to go forward without hearing from the translator, has the staff found other specific failings in its editorial process?

☛ Who specifically decided that this story was fit to air?

☛ In light of the translator’s account, has the staff considered why they discounted the opinions of their sources who doubted Daisey’s contention that Foxconn employs underage workers?

☛ Did the staff consider whether there was another way to air this story without relying solely on Daisey’s account?

☛ Will the show change its vetting procedures as a result of this incident?

☛ Will staff be hesitant to bring performers and others into journalistic stories in the future? Will they handle those situations differently?

☛ Are listeners to understand that all of the stories on “This American Life” should be viewed as literal truth-telling, up to the standards of journalism?

“This American Life” isn’t ready to answer these questions right now.