Ramin Bahrani is the new great American director. After three films, each a master work, he has established himself as a gifted, confident filmmaker with ideas that involve who and where we are at this time. His films pay great attention to ordinary lives that are not so ordinary at all. His subjects so far have been immigrants working hard to make a living in America. His fourth film, now in preparation, will be a Western. His hero will be named Tom. Well, he couldn’t very well be named Huckleberry.

The Old West, too, was a land of immigrants, many of them speaking no English. But Bahrani never refers to his characters as immigrants. They are new Americans, climbing the lower rungs of the economic ladder. There is the Pakistani in “Man Push Cart,” who operates a coffee-and-bagel wagon in Manhattan. The Latino kid in “Chop Shop,” surviving in a vast auto parts bazaar in the shadow of Shea Stadium. The taxi driver from Senegal in “Goodbye Solo,” who works long hours in Winston-Salem, N.C. [“Solo” opens March 27 in Chicago and New York.] These people are not grim and depressed, but hopeful when they have little to be hopeful about. They aren’t walking around angry. Wounded, sometimes. They plan to prevail.

Bahrani doesn’t categorize his characters. I called them outsiders in one of our conversations at Toronto 2008, and he said he liked that. “It’s not just ’emigrant.’ It’s different. Their lives are asking, How should I be as a person, how should I be behaving, why is the world this way? You could put me in a room full of people who look just like me and I would feel like I don’t understand. Those are the questions. It’s in every Herzog film: How do you live in this world? How is the world like this? What else is there to think about?”

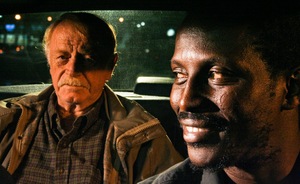

Red West and Souleymane Sy Savané in “Goodbye Solo:” Why do I keep getting you?

Red West and Souleymane Sy Savané in “Goodbye Solo:” Why do I keep getting you?

Bahrani was born in Winston-Salem. His parents emigrated from Iran. “Growing up, it was mainly black, white and me and my brother.” His father was a psychiatrist, working much among poor whites and blacks. After graduating from Columbia University, he went for a few weeks’ visit to his parents’ homeland, and found himself staying several years. He was an outsider there, too. Coming home, he knew he had to make films. “Man Push Cart” was made for a few tens of thousands, a small crew, no permits, and the “catering” sometimes consisted of coffee and pastries from the cart. When it looks like his hero is pushing the heavy cart, that’s because he is. In Pakistan he was something of a rock star. He is trying his fortune in America.

I saw that film at its world premiere at Sundance 2006. Low budget, unheralded. I felt strongly that I was seeing the work of a great director. I felt the same way after seeing Scorsese’s first film. There was an artistic intelligence alive beneath the immediate vision. The images were of real lives on real streets (“mean streets,” Scorsese would call them, quoting Raymond Chandler). In an article about Bahrani and his contemporaries in the latest New York Times Magazine, A. O. Scott calls them “neo-neo realists.” Well, okay. Neorealism was the Italian postwar movement that argued that everyone has one role they are perfect for–themselves. And stories that are perfect for them, about how they live in this world.

Bahrani works with Alejandro Polanco, the star of “Chop Shop,” and Michael Simmonds, who is always his cinematographer

Bahrani works with Alejandro Polanco, the star of “Chop Shop,” and Michael Simmonds, who is always his cinematographer

Bahrani has very rarely used professional actors; none in his first two films, only two in “Goodbye Solo.” They are not playing themselves, but they’re playing people they might have been. Consider the leads in “Goodbye Solo.” We meet Solo, the North Carolina taxi driver from Senegal (Souleymane Sy Savané). By nature he is cheerful, warm-hearted. He lives with a Mexican-American woman and dotes on her daughter. He observes people and cares about them. One day a white man named William (Red West), about 70, gets into his cab, and offers a deal: He’ll pay Solo $1,000 if, in ten days, he’ll give him a ride to the top of a nearby mountain and leave him there. Solo isn’t sure he likes the sound of this.

Souleymane Sy Savané is from the Ivory Coast. Red West is from Memphis. We believe it. They fit into their roles like hands into gloves. You look at Red West and think, this man has been waiting all his life to play this role. He is 72, stands 6’2.” You may have heard the name. He was a member of Elvis Presley’s Memphis Mafia, a friend, driver and bodyguard starting in 1955, who appeared in bit parts in 16 Elvis movies. Since then he has worked for such directors as Robert Altman and Oliver Stone.

“That’s what I’m talkin’ bout, dog!”

“That’s what I’m talkin’ bout, dog!”

“I wanted a real Southerner,” Bahrani told me after the film’s premiere at Toronto 2008. “I wanted the accent, I wanted the mentality of the South. Red sent a video of himself doing a reading of the first scene. I think I watched it for three seconds; I hit pause and said, this is the guy that I wrote about. This is the guy. I called him; I said, ‘Red, can you not point when you do the reading?’ And I gave him one other direction, just to see, would he hear what I said and would he do it? He did it, he taped it, he sent it back; he had listened to everything I said. I brought the guy in and, I mean, there was just no doubt about it. He was the man.”

Bahrani only asked him once about Elvis. “He told a great story. I think it was Elvis’ cousin that was bringing drugs to him in the end, and Red didn’t like it, which was one of the big conflicts of their falling-out. He said, the guy brought drugs, and Red broke his foot and said, ‘I’ll work my way from your foot up to your face.’ “The whole movie is in Red’s face. Especially that lifestyle, you know. The strange thing is he’s really friendly and he loves doing comedic things. He used to apologize to Solo when he was getting mad at him, like, ‘I’m sorry, Solo, I have to do it for the film.’ Only by the fourth week–we did five weeks–did I start to tell him he was doing really good. He knew it by then; he knew he was up to something. After we shot the finale, I had to leave him alone. He went up into that forest and he cried for almost an hour. He was very affected by it. I think he’s great. ‘I’m gonna be discovered at the age 72!’ he tells me.

Chop shop slumdog

Chop shop slumdog

“Solo, he just walked in one day. Didn’t know me, did not know about my films. Just like he’s in the film; charming, warm, open. I liked him immediately. I learned he had been a flight attendant for two years for Air Afrique. I said, ‘do you smoke pot?’ He said yes. I said, ‘do you like reggae music?’ He said yes. I said this has gotta be the guy. Of course, I put him through seven months of hell before I said yes.”

Working with him for months, that’s a key to Bahrani’s approach. His films may feel like scenes from real lives, but they’re meticulously crafted. He doesn’t make them up as he goes along. Before “Chop Shop,” he hung around for a year in that strange alternate New York that the fans in Shea Stadium never see: Blocks upon blocks of shabby buildings with auto repair and salvage shops. Preparing for “Goodbye Solo,” Bahrani rode around Winston-Salem for six months with a real cab driver from Africa: “Charming, friendly, giving–everything that kinda inspiring the character.”

“Goodbye Solo” seems to be about what William will finally do. But the movie is about what happens before. The daily life of Solo. The sealed-off life of William. Solo’s partner and her daughter. William’s lonely movie going. Solo’s concern. William’s hostility toward it. Racism has nothing to do with them. It doesn’t in Bahrani’s films. His characters are wholly absorbed in how they live in this world.

Ahmad Razvi in “Man Push Cart“

Ahmad Razvi in “Man Push Cart“

“Of course I was always an outsider in Winston-Salem. Increasingly I see how my parents are outsiders, how they really don’t seem to belong there. They get along with everyone, everyone gets along with them; there’s never been any instance of latent racism towards them, never. They were always accepted; they love my Dad in the community, he’s a psychiatrist. He never saw wealthy people, he came from Iran with nothing. He’d mainly see the mountain people and the very poor, some poor whites and a lot of poor blacks. They loved him. But I can see how my parents don’t belong and how they’re getting isolated there.”

Bahrani went to Columbia University as an undergraduate. “Then I worked at the North Carolina School for the Arts for one and a half years on staff. I didn’t know how I was gonna get to make a film so I went back to Winston-Salem and thought I should figure it out while I’m writing scripts and things. I worked there on staff at the same time David Gordon Green was there, Craig Zobel, and all these other great people.” Then he moved back to New York, and now teaches a graduate course at Columbia on film directing. One of his tools is to go through the films of his students a shot, sometimes even a frame, at a time.

Sisyphus in Manhattan

Sisyphus in Manhattan

“I tell students the difference between me and you is I made the film and you didn’t. You can make a movie right now with just this hi-def camera and your computer. If it’s gonna be good, I don’t know. That’s a whole different story; that’s a different game.”

I sense that every film, for Bahrani, is like the man pushing the cart. It’s hard to find financing, and sometimes he has had to shut down to raise funds. He’s not making his “latest project.” He’s deciding how he will live for a couple of years. Yet every film looks beautiful. He works with the cinematographer Michael Simmonds. They compose elegantly. You can see their mastery of film grammar. There is never a shot only for style; every shot engages their characters. They are not calling your attention to the film but to its story.

“After finishing this film,” he said, “I was just very depressed and I didn’t understand what was going on in the film industry, or how do you make a film. I was very dark for two or three months; I was like, what am I gonna do? And then I read that that Herzog interview, where he told you that if the world were ending tomorrow, he would start a film. And I said, I’m gonna make a film.”

With Bahrani and Razvi at Ebertfest 2006

With Bahrani and Razvi at Ebertfest 2006

It is a tonic to talk with Ramin Bahrani. He has none of the zealous ego of some filmmakers. No matter what he says, he has found a way to live in this world. He speaks like a friendly young teacher; I’m sure his students regard him as a mentor. Sometimes you hear a faint whisper of a Southern accent, but you have to listen for it. What I hear is the casual friendliness of someone who grew up in Middle America and is driven, not by ambition, but by optimism.

On that afternoon in Toronto, he told me: “I’m starting to realize that no matter if they say film is dying–no matter if they’re telling me you have to do this, you have to do that–I think they’re wrong. I think the more you risk, the better. Did you like the Darren Aronofsky film, ‘Pi?’ Because it risked everything. What the hell is it? I mean, who came up with this thing? The more you risk the better. You just have to find someone who is going to believe, who will put the money up, because it’s usually the opposite of what they tell you have to do. How many people told me ‘no’ to ‘Goodbye Solo?’ How many people told me ‘no, no money, no, no, no.’ Finally, a handful of people said ‘yes.’ They already made their money back at the Venice film festival because I made it so inexpensively. I thank all those people who told me ‘no.’ The more they tell me ‘no’ the happier I become. It makes me angry and I make the movie.”

“Goodbye Solo” opens in Chicago and New York on March 27, and will roll out nationally. Ramin Bahrani, Jim Emerson and I will go through “Chop Shop” with the shot-by-shot approach from 4 to 6 p.m. every day April 6-10 at the Conference on World Affairs at the University of Colorado at Boulder (free and open to the public). “Chop Shop” is also one of my selections at Ebertfest 2009, April 22-26 at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. All passes have been sold, but not all pass-holders attend every screening and in ten years no one in the rush line has ever failed to get a seat.

William wonders why Solo always seems to be his driver:

Solo wants to keep a closer eye on William:

Alejandro Polanco and Isamar Gonzales in “Chop Shop“

Ahmad Razvi in “Man Push Cart”