I am devastated by the death of the great writer Bill Nack, one of Roger’s oldest friends from the day they met at the Daily Illini at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. I send my deepest condolences to his loving wife Carolyne Starek and his four children and grandchildren. Bill was a sports writer, known especially for his turf writing (“Secretariat: The Making of a Champion”), but Bill was quite simply one of the best writers around. His way with words made grown men cry, and his descriptions were so vivid you could see, smell and touch the scenery. Bill loved quoting “The Great Gatsby.” He quoted it at our wedding, and below, Roger and I filmed him quoting it in Chicago at the Caldwell Lillypond near our house in Lincoln Park. But over the years the most romantic times to watch was when he quoted it for his bride, Carolyne. Roger and I were so happy for him when she came into his life over fourteen years ago. They were madly in love until he took his last breath. I like to think that Bill and Roger will be writing passages in the Great Beyond, competing to see whose prose will last for all eternity. Below we are reprinting an article Roger wrote about Bill in 2008 at Rancho La Puerta. Roger called it performing a “Concert In Words.” Chaz Ebert

But don’t forget: you and I reached this conclusion nearly 50 years ago, in the Union, over a cup of coffee, listening to the chimes of Altgeld Hall. So we beat on…

That cup of coffee in the Union cemented one of my oldest friendships. Bill Nack was sports editor of The Daily Illini the year I was editor. He was the editor the next year. He married the Urbana girl I dated in high school. I never made it to first base. By that time, I think he may have been able to slide into second and was taking a risky lead and keeping an eye on the pitcher. We had a lot of fun on the Daily Illini. This was in the days before ripping stuff off the web. He insisted on running stories about every major horse race. We had only one photo of a horse. We used it for every winner. If it was a filly, we flipped it. Of this as his editor I approved.

After college, I was out of the basement of Illini Hall with its ancient Goss rotary press, and running up the stairs. I immediately sat down right here and started writing this. Nack went to Vietnam as Westmoreland’s flack and then got a job at Newsday. On Long Island, he and Mary raised their three girls and a boy. One year at the paper’s holiday party he jumped up on a desk and recited the names and years of every single winner of the Kentucky Derby. Bill told me:

I dismounted from the table in the middle of the city room and Dave Laventhiol, the Newsday editor and closet horse player, came up to me immediately and said, ‘Why do you know that?’ I told him I’d been studying it since I was a kid and loved the history, color and lore of the racetrack. “It’s the Damon Runyan in me,” I said.

“Would you like to cover the races for Newsday?” he asked.

Five minutes later, after consulting with wife Mary, I was the Newsday turfwriter.

Voila! Laventhol asked me to write a note asking for the job, so he could post it on the bulletin and not have to explain this unusual move to everyone thinking I’d lost my mind. The only thing I can remember of that memo was this: “After covering politicians for four years, I would like the chance to cover the whole horse.”

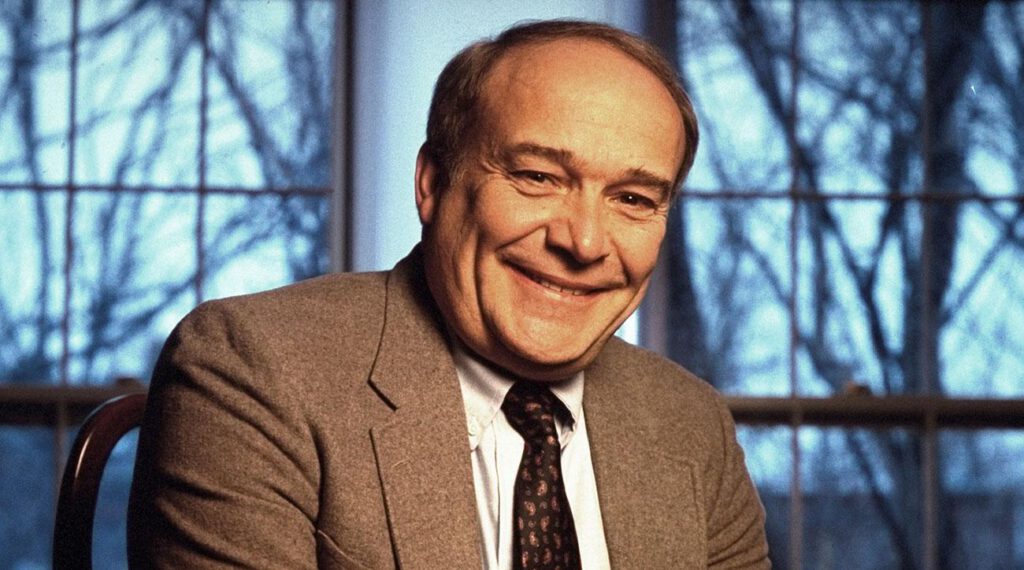

Bill Nack, a performer in words. (Photo by Roger Ebert)

Bill was part of the story of Secretariat from before the great horse was born, or maybe a few days later, I forget the details. Discovering the greatest horse in history became the greatest event in his professional life, as seeing Scorsese’s first film became mine. Bill saw the stallion for the last time very shortly before his death. “After the autopsy, the vet said he had a heart twice as big as the average horse,” Bill told me. “There was nothing wrong with it. It was simply a great heart.” He wrote about this in the best-seller Secretariat: The Making of a Champion, which is now being made into a movie.

By then he was working for Sports Illustrated, where he became a senior writer. He wasn’t the kind of writer who covered a particular beat. He was and is a great American prose stylist. At a reading for his book My Turf, he read a story and made a woman cry. Then he read another story and there wasn’t a dry eye in the house. One was about the death of Secretariat. The other was about a filly breaking down and being destroyed on the track.

Bill was the writer who exposed the scandal of how owners and vets conspired to use cortisone in order to race horses who were not ready to be raced. “I started seeing horses breaking down all the time,” he said. “You hardly ever used to see that.” No one at the tracks would give him the time of day for a couple of years. It was a rotten business.

Nack has met everyone. Here is the kind of thing that happens to him. It is from the opening of an article he and our mutual friend Lester Munson wrote for ESPN.com, where Bill now works as a commentator. Munson is speaking:

On Sunday, as I was sitting in my summer cabin in Vermont, completely absorbed in a New York Times story about John Edwards’ affair with Rielle Hunter, I began reading a paragraph whose message shot through me like a sudden bolt of electrical current. The story centered on Ms. Hunter’s refusal to take a DNA test to determine the paternity of her 5-month-old daughter, but that was not what startled me. It was this: “Ms. Hunter was born in Fort Lauderdale. Fla., in 1964 as Lisa Druck and moved to New York City in her 20s, becoming part of a Manhattan social scene that included the writer Jay McInerney …

Here, I jumped up and blurted loudly to my wife, Judy: “Good God! John Edwards was having sex with the daughter of the guy who taught Tommy Burns how to kill horses by electrocuting them!”

Bill covers the waterfront. One of his stories involved tracking down every eyewitness he could find to the Long Count fight between Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney.

All this is prelude. My favorite spa in all the world is Rancho la Puerta in Tecate, Mexico. If I say it is my favorite, somehow you know it is not Bianca Trump’s favorite. Bill was like me until Chaz dragged me kicking and screaming down there. He didn’t need no stinking spa. I talked him into it with the help of his wonderful wife Carolyne. Yes, they loved it. We all meet there at least once a year. I wrote Rancho telling them Bill was the most gifted reader I had ever heard, and so he is, reciting his choices from memory, including “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and no end of Yeats. We started reading together in Boulder at Diane Doe’s book shop, during the Conference on World Affairs. When Bill visited me in Chicago right after the Obama victory, he was memorizing one of the e. e. cummings poems I always used to read, which begins:

anyone lived in a pretty how town (with up so floating many bells down) spring summer autumn winter he sang his didn’t he danced his did

I appointed myself as Bill’s impresario. I told Rancho they should schedule an evening titled “A Concert in Words, with William Nack.” That’s exactly what you want at 8 p.m. after you took the morning mountain walk and busted your ass in the gym all day, right? Some guy standing up there readin’ po-ems. The room was pretty full however, because I ‘d been working the dining room at meal times, flogging the great event.

Bill dimmed the lights just a little, and read for an hour, mostly standing in front of the podium without a book. The campers demanded an encore. He read for another 30 minutes. Then he got a standing ovation and they marched on the concierge to demand a second performance. He read the next afternoon for another hour, but he had to stop at six because you don’t want to be late for dinner after busting your ass all day.

I have heard Bill read maybe 20 or 30 times. We both read books all the time. He reads them like a musician searching for notes. When he finds something he’s like a kid. Of all writers I believe he loves Nabokov the most. He’ll give you the opening page of Lolita or passages from Speak, Memory. “There’s something I want you to hear,” he told me one morning on a hike. He always starts that way. “It’s from Nabokov’s Pnin. Have you read it? About a university professor. I think this might be the most profound metaphor I’ve ever found.

With the help of the janitor he screwed on to the side of the desk a pencil sharpener–that highly satisfying, highly philosophical instrument that goes ticonderoga-ticonderoga, feeding on the yellow finish and sweet wood, and ends up in a kind of soundlessly spinning ethereal void as we all must.

One sentence. Perfect. The sound, the image, the shrugging resignation. No comma after void. To fully appreciate it, it has to be read aloud. Get somebody in your house, or call somebody on the phone. I can wait.

When Bill is doing a reading, I want to call out requests like a drunk who can never get enough of “Melancholy Baby.” Frost! Seamus Heaney!

Vladimir Nabokov and a Ticonderoga

I still have the first real book I ever read. It has a passage I want him to read someday. He’s holding the very volume it in that photo. It is The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The inscription says, “To Roger from Uncle Bill, Christmas 1949.” I was halfway into second grade.

My grandmother, Anna B. Stumm, said, “Do you think Roger can read that, Bill?”

Uncle Bill said, “Bud, can you read?”

“Yes,” I said. “Then he can read it.”

I lay down on my stomach on the living room rug and started reading. I hardly stopped. “That boy always has his nose in a book,” my Aunt Mary said. “Mary, he’s reading,” my Aunt Martha said. I didn’t know a lot of the words, but the words I did know were a lot more interesting than “Run, Spot, run!” and I picked up new ones every time through, because I read it over and over for a year, getting to the end and turning straight back to “You don’t know me without you have read a book by Mr. Mark Twain…” It was the best book I had ever read.

I’ve read Huckleberry Finn I don’t know how times. At the University of Cape Town I grew sentimental about Johnson’s 1964 Civil Rights Act, and read it again. “All American literature comes out of a book by Mark Twain named Huckleberry Finn,” Hemingway wrote, measuring it out in that reporter’s way of his. It is a profound turning point in the American dialogue between black and white, all told in Huck’s Mississippi River dialect.

Mark Twain was a magnificent stylist. I’d never read one word of James Fenimore Cooper when I read Twain’s Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses in about the fifth grade. I didn’t need to, Twain was so damnably funny. His essay had a direct and obvious influence on many of my reviews. Whenever I start picking the logic of a plot to shreds, I am Mark Twain’s pupil. Here is a sample:

Cooper’s gift in the way of invention was not a rich endowment; but such as it was he liked to work it, he was pleased with the effects, and indeed he did some quite sweet things with it. In his little box of stage properties he kept six or eight cunning devices, tricks, artifices for his savages and woodsmen to deceive and circumvent each other with, and he was never so happy as when he was working these innocent things and seeing them go. A favorite one was to make a moccasined person tread in the tracks of the moccasined enemy, and thus hide his own trail. Cooper wore out barrels and barrels of moccasins in working that trick. Another stage-property that he pulled out of his box pretty frequently was his broken twig. He prized his broken twig above all the rest of his effects, and worked it the hardest. It is a restful chapter in any book of his when somebody doesn’t step on a dry twig and alarm all the reds and whites for two hundred yards around. Every time a Cooper person is in peril, and absolute silence is worth four dollars a minute, he is sure to step on a dry twig. There may be a hundred handier things to step on, but that wouldn’t satisfy Cooper. Cooper requires him to turn out and find a dry twig; and if he can’t do it, go and borrow one. [1]

Natty! Natty Bumppo! Look out for your right foot!

There you hear Twain’s voice, genial, direct, and poker-faced. He could be poetic when he wanted to, but he never seemed to be reaching for an effect. He had that gift of using only the words that seemed natural, even inevitable, to use. No adornments. And he could do that in dialect, as he does with Huckleberry Finn.

Call your audience back into the room and read them this, from Huckleberry Finn, which I believe Bill is memorizing:

Pretty soon it darkened up, and begun to thunder and lighten; so the birds was right about it. Directly it begun to rain, and it rained like all fury, too, and I never see the wind blow so. It was one of these regular summer storms. It would get so dark that it looked all blue-black outside, and lovely; and the rain would thrash along by so thick that the trees off a little ways looked dim and spider-webby; and here would come a blast of wind that would bend the trees down and turn up the pale under-side of the leaves; and then a perfect ripper of a gust would follow along and set the branches to tossing their arms as if they was just wild; and next, when it was just about the bluest and blackest — fst! it was as bright as glory, and you’d have a little glimpse of tree-tops a-plunging about away off yonder in the storm, hundreds of yards further than you could see before; dark as sin again in a second, and now you’d hear the thunder let go with an awful crash, and then go rumbling, grumbling, tumbling, down the sky towards the under side of the world, like rolling empty barrels down stairs — where it’s long stairs and they bounce a good deal, you know.

How did you think Mark Twain wrote? Four sentences. The fourth one 179 words long. As a boy, I thought it was the realest thunderstorm I had ever seen. It plays like Beethoven. Mark Twain introduced America to its vernacular. Not how we speak, but how we caress and feel words. Before him, there were great writers like Poe and Melville, who I still read with love. But I sit on the porch steps next to Sam Clemens in his rocking chair, and he speaks in the voice of his Hannibal childhood–straight and honest, observant and cynical, youthful but wise, idealistic and disappointed, always amused, and sometimes he rolls the words down stairs–where it’s long stairs and they bounce a good deal, you know. They bounce themselves right into poetry.

The long sentence isn’t a stunt. Thunderstorms do seem to sustain themselves forever and then suddenly lull and regather. The flashes and claps punctuate the constant rolling uneasiness. I don’t know if you can describe one in short sentences. That was the limitation of Hemingway’s style. “Grumbling, rumbling, tumbling” when it comes is not an effect, but like all good descriptions simply the best way to say it, evoking the way storms wander away from us, still in turmoil. Look how he uses fst! to break the flow.

Pretty soon it darkened up, and begun to thunder and lighten; so the birds was right about it. The word was throughout is always better than the word were, and keeps Huck’s voice in view. The remarkable thing is that we accept this poetic evocation as the voice of an illiterate boy. Darkened up is better than darken, and darkened down would be horrible. Lighten is the right word, perhaps never before used like this, allowing him to avoid the completely wrong thunder and lightning, without having to write the pedestrian and there was thunder and lightning. It keeps it in Huck’s voice. An English teacher who corrects lighten should be teaching a language he doesn’t know. And look at these words: It would get so dark that it looked all blue-black outside, and lovely…No, don’t look at them. Get a musician to compose for it. Notice how lovely softens the blue-black and nods back to it soothingly.

While I was anticipating Bill’s visit to Chicago and musing about this essay, a reader named Luke posted a blog comment beginning, “For my money, the greatest lines in literature come at the end of the The Great Gatsby.” Then he quoted some of them.

The green light at the end of Daisy’s pier

I e-mailed the comment to Bill, who responded with the lines at the top of this entry. After that cup of coffee in 1961 at the Ilini Union, I’ve heard Bill recite those very lines, conservatively, a hundred times. He even performed them at our wedding banquet. And at his own with Carolyn, of course. And every Wednesday night during the Conference on World Affairs in Boulder, when a group of pals would have dinner together at the Red Lion Inn up the mountain. Yes, the night Studs Terkel and Molly Ivins were there.

Most of the big shore places were closed now there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferryboat across the Sound. And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes–a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

And as I sat there brooding about the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter–to-morrow we will run faster, stretch our arms our further . . . And one fine morning —

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

If The Great Gatsby is, as some people believe, the greatest American novel, there’s the most important reason right there. Fitzgerald does what no writer should do, and reveals his cards. He states his theme in so many words. He sums up. Not cool. The theme should be implied. It should be expressed with indirection, as if about something else. It should coil secretly among the words. Yes, yes, yes, and the hell with it. A great writer knows not only when to break the rules, but how to. How could you change one word of the sentence beginning, Its vanished trees…

If The Great Gatsby is, as some people believe, the greatest American novel, there’s the most important reason right there. Fitzgerald does what no writer should do, and reveals his cards. He states his theme in so many words. He sums up. Not cool. The theme should be implied. It should be expressed with indirection, as if about something else. It should coil secretly among the words. Yes, yes, yes, and the hell with it. A great writer knows not only when to break the rules, but how to. How could you change one word of the sentence beginning, Its vanished trees…

Now gather your audience again. That is the paragraph that started Bill Nack off on a lifetime of memorizing. His most beloved passage of American prose, and mine. Read it to them. Bill tells me his pal Hunter S. Thompson once warmed up by copying out every word of The Great Gatsby on his typewriter. Not that you can immediately see Fitzgerald’s influence in Hunter’s style, although perhaps the words compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired is the best possible description of Thompson’s life’s work.

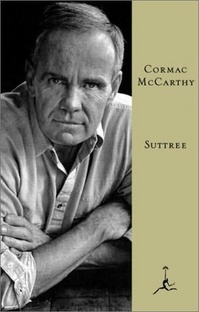

And now we arrive, as you knew we must, at Cormac McCarthy‘s Suttree. I have read all of McCarthy’s fiction, and for my money this is his best novel, but (“therefore,” I want to add) appears to be his least-mentioned. Just read this:

Ooh coal, kindling wood Would if i could Hep me get sold Coal now

The most recent time I read those words, it was 10 o’clock at night in the rehab center. Dead quiet, in the dead of winter. My room chilly. I was holding the book while seated in a wheelchair by the side of my bed. The wheelchair tilted back to ease the pain of my shoulders, where flesh had been removed to try to patch the hole in my chin. I had a blanket wrapped around me, even covering my head and the back of my neck.

When I was drinking, I went to O’Rourke’s on North Avenue, which was heated in the early days only by a wood-burning stove. Dress warmly and drink in a cool room, was my motto. Now in the hospital those cold, cold words of McCarthys’ transported me. At a point beneath desire, I was there on Suttree’s leaking houseboat in the hopeless dawn, sharing the ordeal of Suttree, the general, and Golgotha. It was an improvement. I was not trapped in a bed and a chair. I was not hooked up to anything. I was miserable, but I was alive, and McCarthy was still able to write that perfect terse dialogue. That is the thing about McCarthy. He is both the teller and the subject of Suttree. I do not mean anything so banal as that the book is autobiographical. It is the merciless record of a state of mind, the alcoholic state of mind, even when Suttree is not drinking but is white-knuckling it.

Do not assemble your audience again. First, I want you to read those words to yourself one more time. Go away and have a cup of coffee. What works for me, I start with a good teaspoon of instant, and then I stir in a scant teaspoon of Postum, just a little cocoa powder, and some skimmed soy milk.

Are you back now? Then read McCarthy again. How at the top he writes the horse named Golgotha hung between the trees and at the bottom he writes where the horse stands sleeping in the traces. Trees above, and traces below. Hung between the trees goes up, and makes the death and Crucifixion connection without stating it. Sleeping between the traces goes down, and closes. Reverse the use of the trees and traces and see how you like them now.

Regard the pedlar’s cry:

Ooh coal, kindling wood Would if i could Hep me get sold Coal now

How did this construct itself for the old man over the years? What cry of need softened into a song? Has it grown into solace, or is it only a hopeless chant? How must it sound approaching over the frozen fields? …the horse named Golgotha hung between the trees and stumbling along in the cold with his doublejointed knees and his feet clopping and the bright worn quoits winking feebly among the clattering spokes. Which evokes the awkwardness and the agony and the sound and the sight. You don’t know what a quoit is, but you know by reading it. And then: In the whipsocket rides a bent cane. A short sentence to bring a full stop to the long one.

The general climbs and climbs down from his seat… This sentence is in a different universe than The general climbs down from his seat, which would be jarringly pedestrian. The old black coalpedlar sat his cart, the horse sidled and stamped. The right sentence. The wrong one would be: The old black coal peddler sat on his cart, and the horse sidled and stamped. The word and would turn it from evocation into description. The horse sidled. The wrong words would be: shivered. stirred. shook. The right word:

sidle |ˈsīdl| verb [intrans.] walk in a furtive, unobtrusive, or timid manner, esp. sideways.

The novel is written entirely with that attention. You haven’t even started it until you’ve started it the second time. After weeks of depression, hopelessness and regret, realizing the operation had failed and I would probably not speak again, after murky medications and no interest in movies, television, books or even the morning paper, it was the bleak, sad Suttree that started me to life again. Spare me happy books that will cheer me up. I was fighting it out with Suttree. I didn’t want a condo in Florida. I wanted a fucking basket of coal. I picked up the book indifferently and started it the third time, after another failed surgery and at another low ebb because “at least I know it’s good.” Nor was I inspired by Suttree’s struggle. I was inspired by McCarthy’s. I sensed that McCarthy in every moment at his work was like Suttree waiting for the doublejointed Golgotha to stumble down the hill.

I don’t believe Cormac McCarthy is an alcoholic. But I believe he knows what one is. Suttree is the most true account of being drunk, being hung over, and the temporary elation of possible sobriety that I have ever read, better than Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, because it is written from the outside, and Lowry was still inside. No good movie is depressing, I like to say. All bad movies are depressing. I once ordered ballpoints bearing that motto, and gave them away to idiots. In that long season of my life, Suttree affirmed the worth of getting the hell up and starting over again. Not long after, Chaz brought me the DVD of “Queen” and said, “I think you might like this one.” I did. I took one of her yellow legal pads, me who had not written in longhand since high school, and wrote my review, Suttree glancing in my direction.

What did they receive from Bill’s reading, the audience at Rancho la Puerta? From 90 minutes of great poetry and prose, told to them by a master? In their real lives they are busy getting and spending, as we all must. I believe Bill reawakened in them the restless stirring we all felt, taking a class in literature, when we were asked to read someone we found that we loved, like Jane Austen, Emily Dickenson, Mark Twain or Shakespeare. In those days we walked with kindred spirits on the Quad in the moonlight and shared our aspirations. Now here was Bill, starting again:

Whose woods these are I think I know…

At that moment for them he was the green light at the end of Daisy’s pier.

[Footnote 1] Mark Twain’s Rules for writing: Cooper’s art has some defects. In one place in ‘Deerslayer,’ and in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offences against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.

There are nineteen rules governing literary art in the domain of romantic fiction–some say twenty-two. In Deerslayer Cooper violated eighteen of them. These eighteen require:

1. That a tale shall accomplish something and arrive somewhere. But the Deerslayer tale accomplishes nothing and arrives in the air.

2. They require that the episodes of a tale shall be necessary parts of the tale, and shall help to develop it. But as the Deerslayer tale is not a tale, and accomplishes nothing and arrives nowhere, the episodes have no rightful place in the work, since there was nothing for them to develop.

3. They require that the personages in a tale shall be alive, except in the case of corpses, and that always the reader shall be able to tell the corpses from the others. But this detail has often been overlooked in the Deerslayer tale.

Mark Twain: No rule against writing in bed

4. They require that the personages in a tale, both dead and alive, shall exhibit a sufficient excuse for being there. But this detail also has been overlooked in the Deerslayer tale.

5. They require that when the personages of a tale deal in conversation, the talk shall sound like human talk, and be talk such as human beings would be likely to talk in the given circumstances, and have a discoverable meaning, also a discoverable purpose, and a show of relevancy, and remain in the neighborhood of the subject in hand, and be interesting to the reader, and help out the tale, and stop when the people cannot think of anything more to say. But this requirement has been ignored from the beginning of the Deerslayer tale to the end of it.

6. They require that when the author describes the character of a personage in his tale, the conduct and conversation of that personage shall justify said description. But this law gets little or no attention in the Deerslayer tale, as Natty Bumppo’s case will amply prove.

7. They require that when a personage talks like an illustrated, gilt-edged, tree-calf, hand-tooled, seven-dollar Friendship’s Offering in the beginning of a paragraph, he shall not talk like a negro minstrel in the end of it. But this rule is flung down and danced upon in the Deerslayer tale.

8. They require that crass stupidities shall not be played upon the reader as “the craft of the woodsman, the delicate art of the forest,” by either the author or the people in the tale. But this rule is persistently violated in the Deerslayer tale.

9. They require that the personages of a tale shall confine themselves to possibilities and let miracles alone; or, if they venture a miracle, the author must so plausibly set it forth as to make it look possible and reasonable. But these rules are not respected in the Deerslayer tale.

10. They require that the author shall make the reader feel a deep interest in the personages of his tale and in their fate; and that he shall make the reader love the good people in the tale and hate the bad ones. But the reader of the Deerslayer tale dislikes the good people in it, is indifferent to the others, and wishes they would all get drowned together.

11. They require that the characters in a tale shall be so clearly defined that the reader can tell beforehand what each will do in a given emergency. But in the Deerslayer tale this rule is vacated.

In addition to these large rules there are some little ones. These require that the author shall:

12. Say what he is proposing to say, not merely come near it.

13. Use the right word, not its second cousin.

14. Eschew surplusage.

15. Not omit necessary details.

16. Avoid slovenliness of form.

17. Use good grammar.

18. Employ a simple and straightforward style.

This piece was originally published on December 8, 2008.

Header photo credit: Katherine Lambert