Rating: Four stars

Consider now the curious character of Dr. King Schultz. He is an itinerant dentist who works from his little wagon, traveling the backroads of the pre-Civil War South. As Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained” opens, we see a line of shackled slaves being led through what I must describe as a deep, dark forest, because those are the kinds of forests we meet in fairy tales. Out of this deepness and darkness, Schultz (Christoph Waltz) appears, his lantern swinging from his wagon, which has a bobbling tooth on its roof.

1/8/13: I added material involving Stephen, played by Samuel L. Jackson.For the record: My star rating would be: Four stars.Yes, had I not been prevented from seeing it sooner because of an injury, this would have been on my year’s best films list,

Schultz explains himself with the elaborate formality he will use all through the film. He has reason to believe one of the slaves might be of interest to him. This is the slave named Django (Jamie Foxx). He enters into negotiations to purchase Django, who he has reason to believe may help him in finding the Brittle brothers, for reasons involving the doctor’s late wife.

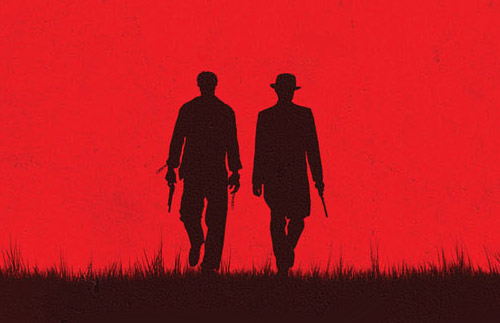

And already Tarantino has us, and it’s off to the races. The film offers one sensational sequence after another, all set around these two intriguing characters who seem opposites but share pragmatic, financial and personal issues. We never look back. Maybe it’s just as well.

But now I must ask, before the plot hurtles ahead: Does it strike you as strange that Dr. King Schultz, in all of the vastness of the South, should have been driving his wagon through just that very deep, dark forest where Django was being led? How could he have even known about that? How odd that the path of the wagon and the slaves, which should have sailed past one another like two ships in the night, should meet head to head?

Let us leave Dr. Schultz engaging in one of his several financial transactions during the film, fueled by a generous supply of cash. Let us explain him. He is a wizard from a fairy tale, a man capable of knowing about people’s lives, steering their fates, seducing them into situations in which they receive the destinies they deserve. Although there is a great deal of the realistic in “Django Unchained,” including brutal violence, King Schultz is not real in the same way as the rest.

I require the term deus ex machina. I apologize to my many readers who already know it. A “deus,” for those few who may not, is a person or device in a story that appears from out of the blue and has a solution to offer. I quote Wikipedia: “The Latin phrase deus ex machina comes to English usage from Horace’s Ars Poetica, where he instructs poets that they must never resort to a god from the machine to solve their plots. He refers to the conventions of Greek tragedy, where a crane (mekhane) was used to lower actors playing gods onto the stage.” Imagine Tarantino, his feet braced on clouds, lowering Dr. Schultz into “Django Unchained” and using him as a wonderfully useful device to guide the plot wherever it must go.

In the film we’ll find that Dr. Schultz, who we never see pulling any teeth, is a bounty hunter, searching for men who are wanted–“dead or alive.” Here is a plot that requires a lot of information, and doesn’t have any time to lose in introducing it or searching for it. Schulz not only knows who and where Django is, but he knows where certain wanted men can be found, living under aliases. He shoots a sheriff and calmly explains why. He produces the Wanted posters from his bottomless wallet. His knowledge allows Tarantino to set up perfectly entertaining scenes in which it appears Schultz digs himself into holes and then escapes from them.

He also becomes the friend and partner of Django, gives him his freedom, and after a winter spent in using Django as his partner in bounty hunting, joins with him in trying to win back possession of Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), Django’s wife. Why does he do this? Because he likes Django and hates slavery. This is a convenience making QT’s story telling much easier.

This is a brilliant entertainment, in which Tarantino takes on the subject of slavery as he did the Holocaust in his previous film, “Inglourious Basterds.” That one, too, employed Christoph Waltz in a leading role, using his German-accented formalities to talk his way through situations. Tarantino loves dialogue and lets it run at unusual length for the quasi-exploitation genre. Consider QT’s audacity in allowing “Basterds” to open with so much verbiage. Tarantino is a man who tells us his early job was in a video store, where, if this can be believed, he viewed virtually every video. He left that job in 1989. Five years later, I was talking to him at Cannes, where the video store clerk from Knoxville had entered “Pulp Fiction,” the eventual Palme d’Or winner. One thing he didn’t learn from those exploitation classics was the art of sparse dialog. You can almost imagine his relish in retelling the stories of his favorite films in more detail than they used.

Because “Django” is so filled with violence and transgressive behavior, he told me something that day that’s worth remembering when discussing “Django:” “When I’m writing a movie, I hear the laughter. People talk about the violence. What about the comedy? ‘Pulp Fiction’ has such an obviously comic spirit, even with all the weird things that are happening. To me, the most torturous thing in the world, and this counts for ‘Reservoir Dogs’ just as much as it does to ‘Pulp,’ is to watch it with an audience who doesn’t know they’re supposed to laugh. Because that’s a death. Because I’m hearing the laughs in my mind, and there’s this dead silence of crickets sounding in the audience, you know?”

I sorta know. There were however some dead crickets in my mind during the scene in “Django Unchained” where we visit a Southern Plantation run by a genteel monster named Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), who for his after-dinner entertainment is having two slaves fight each other to the death. It’s a brutal fight, covered with the blood that flows unusually copiously in the film. The losing slave screams without stopping, and I reflected that throughout the film there is much more screaming in a violent scene than you usually hear. Finally the fight is over, and there’s a shot of the defeated slave’s head as a hammer is dropped on the floor next to it by Mr. Candie. The hammer, (off-screen but barely) is used by the fight’s winner to finish off his opponent.

At this point in the film I found myself mentally composing a letter to Quentin, explaining why I stopped watching his film. The letter went unwritten. There are such scenes in most Tarantino films. Do you remember Michael Madsen cutting off the cop’s ear in “Reservoir Dogs?” When QT begins a movie, I believe, his destination is to aim over the top. The top itself will not do.

We know that he is a student and champion of exploitation films. He digests their elements and reforms them at the highest level of their ambitions. The point of the exploitation genre is to grab people on the basis of the shocking material itself, regardless of such elements as movie stars, budgets, artistry, profundity or anything else. In the hearts of many moviegoers there stubbornly lurks the desire to be… exploited.

This is an irrefutable fact: On the post-holiday weekend I’m writing, “Django” ended second at the box office with $20 million. “The Hobbit” was third with $17.5 million, and “Les Miserables” fourth with $16 million. The weekend’s #1 top-grossing film was a retread, “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 3D,” with $23 million. This could be misleading; “Django’s” current total is $106 million after only two weeks, but it’s revealing.

What Tarantino has is an appreciation for gut-level exploitation film appeal, combined with an artist’s desire to transform that gut element with something higher, better, more daring. His films challenge taboos in our society in the most direct possible way, and at the same time add an element of parody or satire.

Consider the fight scene I described. Where is the comedy? Tarantino says he hears laughter in his mind. Why? I suspect it’s because this entire film takes the painful, touchy subject of slavery and approaches it without the slightest restraint. At some point in the scene, QT’s laughter may be because the audience expects to see violence but doesn’t expect to get it a such an extreme; he’s rubbing it in.

The film is often beautiful to regard. Tarantino’s Southern plantations are flatlands in spring, cloud-covered, with groups of slaves standing as figures in a landscape. His film leads us all the way to Candyland, where the odious Calvin Candie owns Django’s wife Broomhilda von Shaft (Kerry Washington). Candie stages fights to the death with slaves called Mandingos, and Schultz says he wants to buy one of the fighters. He says he’ll throw in a little extra for Candie’s slave women Broomhilda, because she speaks German and he yearns to speak his native tongue.

That’s clever misdirection with the mandingo as a cover story. Candie believes it. Not everybody at Candyland does. This is such a flamboyant film that the most challenging performance in it, the one that rubs it in the most, actually runs the risk of being overlooked. That is Samuel L. Jackson’s work as Stephen, Calvin Candie’s most favored and privileged slave. He acts as butler and chief of staff at Candyland. He is well-dressed, treated with (relative) respect by Candie, and seen by the other slaves as no better than a racist white–worse, because he betrays his race. He is the classic Uncle Tom, elevated to Granduncle Thomas, Esq.

There’s a telling scene where Stephen and Calvin relax behind closed doors at the end of the day, sharing snifters of brandy. In these closed quarters, they might be equals. I was reminded of “Downton Abbey” and the privileged conversations between the Earl of Grantham and the butler Carson. No doubt Stephen leads the most comfortable life possible for a slave at that time, but what a price he pays! No one has glowering eyes that threaten more than Jackson’s, and we can all but read his mind as he regards Django, Broomhilde and Schultz and sees through Schutz’s story that he wants to pay a preposterous price just for someone to speak German with. He confronts Calvin with the obvious: It is Django who loves Broomhilde and desires her.

Revealing this truth involves Stephen in a betrayal that in some respects is the most hateful action in the movie, because he sins not only against the others but against himself. He confirms that in some putrid sinkhole of his soul, he regards himself as white. How Tarantino deals with the consequences of his betrayal sets the whole ending of the film into motion, with its satisfactory Quentonian celebration of violence, explosions, all that stuff. Stephen is also, if you will, a deus, cranked down onto the stage so his realizations can cut through revelation of the secret the others share. He works for that purpose, but also, in a film that condemns white racism, is also capable of seeing black racism.

Stephen is a crucial character because he forces African-American viewers to acknowledge the role some of their forebearers played at the time. Just as more recently in South Africa, a system in which one person rules ten is made possible by the cooperation of some of the ten. It is a hard, unavoidable fact. Jackson’s performance requires not only his gifts as an actor but his courage as a man who understands the utility of an obvious role and is willing to play it.

The name “von Shaft” also reflects QT’s wicked fondness for bringing distracting and outlandish names into the midst of dead-serious and violent material, as sort of a signal to the audience that Tarantino knows he’s treading on the edge of parody. Tarantino’s predecessor, Russ Meyer, also loved to saddle his characters with unexpected names; in “Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens,” we find Eufaula Roop, Mr. Peterbilt, Dr. Asa Lavender, Semper Fidelis, Norse Flovilla Thatch and Beau Badger. (The name “Eufaula,” Russ told me, came from the name of the Southern town where one of his old Army buddies lived.)

“Django” has been criticized for its overuse of the n-word, a long-standing charge against Tarantino. In this case, although the total comes to over 100, I understood it as a word in common daily use through the antebellum South. In context, there was a reason for it. The film has also been attacked for its incredible level of violence, and that’s what I was responding to in composing my imaginary letter to Tarantino. Yes, it deserves its R rating and in an earlier day might have drawn the X. But it’s not what a film does but how it does it, and in one sense the violence here reflects Tarantino’s desire to break through audience’s comfort level for exploitation films and insist, yes, this was a society and culture that was inhuman.

Tarantino attacks at all levels. One of his most inspired scenes involves the Klan members bitching and moaning that they can’t see through the eye-holes on the hoods over their heads. In everything but subject, that could be from a Looney Tunes movie. QT is grandiose and pragmatic, he plays freely with implausibility, he gets his customers inside the tent and then gives them a carny show they’re hardly prepared for. He is a consummate filmmaker.

Looking at his IMDb entry, I find that Tarantino has a film in pre-production that will be some kind of retread of Russ Meyer’s “Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!” That’s the film John Waters has described as “not only the greatest film ever made, but the greatest film that ever will be made.” For Tarantino, the lure of the title alone must have been irresistible, a tug in the back of his mind from those long-ago video store days.