When people cheerfully tell me, “I have a trivia question” for you, I have a cheerful answer for them, but I rarely express it: “I’m a professional. Ask an amateur.” Why in the name of Buster would I want to clutter my memory with useless facts? During long, hard years of being asked trivia questions, I have learned one thing for sure. The person asking me is in the possession of one fact, and is pretty confident I don’t know it. Therefore, my admission of defeat will demonstrate their superiority.

When people cheerfully tell me, “I have a trivia question” for you, I have a cheerful answer for them, but I rarely express it: “I’m a professional. Ask an amateur.” Why in the name of Buster would I want to clutter my memory with useless facts? During long, hard years of being asked trivia questions, I have learned one thing for sure. The person asking me is in the possession of one fact, and is pretty confident I don’t know it. Therefore, my admission of defeat will demonstrate their superiority.

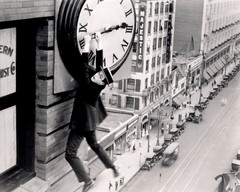

I know something about the movies, and here is how I really should reply: “Before I even attempt to answer your question, let me ask you five questions to see if you are qualified to even take up the time of a busy, busy man such as myself. (1) What is the name of the film that codified the language of the cinema? (2) Who was the third great silent clown? (3) Is color intrinsically better than black-and-white? (4) What movie set key scenes on board a train going from Chicago to Urbana, Illinois? (5) Name at least five directors of the French New Wave.

I know the answers. [1] Not everybody can be expected to. Therefore, I am smarter than you? No, we just know different things. I would argue that the answers to all but Question Number 4 are part of the armory of a well-informed cineaste. Number 4, of course, is gold-plated trivia.

The reason game shows like “The Price is Right” are popular is because most viewers think they know the approximate answer. The reason “Wheel of Fortune” is one of the longest-running shows on TV is that anybody but a dunderhead can sit at home, observe the letters as they fill in the blanks, and usually provide the answer more quickly than the contestants can.

From 1959 to 1970, there was a TV game titled “College Bowl,” on which teams from various universities competed to see which could more quickly supply the answers to questions testing general, but not trivial, information. The University of Minnesota traditionally fielded winning teams. The show’s popularity faded as audiences gradually lost their interest in smart people. This was years before the term “the elites” came into favor.

The reason a quiz show based on movie trivia has never been successful is that no viewer can be expected to know any of the answers. If they do, the answers are too easy. Example: “Who played the first Tarzan in the movies?” Answer: “Elmo Lincoln.” A surprising number of people know this. Never mind that they are wrong. The correct answer would be the child actor who portrayed the son of Lord and Lady Greystoke, the infant who grew up to become Tarzan. “Tarzan” was the first name he knew.

My friend McHugh posed this question to the distinguished film director Gregory Nava, who lost a $10 bet that to this very day he has refused to make good on. Nava fumed that McHugh had pulled a low trick based on a technicality. He had reason to be annoyed. Nava is scholarly on the subject of film, and McHugh claims he has seen only one film in his entire life, “How Green Was My Valley.” In his memory this was always playing in his hometown of Sligo. Every time he was told to take his younger brothers to the movies, he brought them back home and nine months later there was another brother. Eventually there were ten McHugh brothers, so you can understand how he came to resent the movies.

The younger Greystoke was played by Gordon Griffith, who was 10. You must admit that from a standpoint of pure logic, McHugh was right. Nava’s refusal to pay off the bet is based on labyrinthine reasoning which boils down to “That’s no fair!” No one ever asks you a trivia question they have the slightest reason to believe you will know the answer to. There are few sights in the course of conversation more gratifying than the deflated face of a trivia “expert” whose question has been correctly answerer.

To be sure, trivia sometimes serves a useful purpose. During a boozy office Christmas part at Newsday, my friend Bill Nack once leaped upon the City Desk and correctly recited the names of every single one of the winners of the Kentucky Derby. As a result, he won the job of the newspaper’s turf reporter, a position that eventually led him to Sports Illustrated, made him the biographer of Secretariat, and had Frank Whaley portraying him in “Ruffian” (2007.)

The very sight of the words “Ruffian” (2007) leads me into another area of trivia. For some reason we film crickets like to follow the titles of films with their year, in parenthesis. We all walk around with hundreds of release years in our memories. This is not the convenience it might seem, because the year always has to be checked on IMDb anyway.

The fatal flaw in the concept of trivia is that it mistakes information for knowledge. There is no end to information. Some say the entire universe is made from it, when you get right down to the bottom, under the turtles. There is, alas, quite a shortage of knowledge. I think I will recite this paragraph the next time I’m asked a trivia question.

[1] Footnote: “The Birth of a Nation;” Harold Lloyd; No, it is an artistic choice; “Some Like It Hot;” Varda, Godard, Truffaut, Chabrol, Resnais, Rivette, Rohmer. However, I am mistaken about “Some Like It Hot.” Gotme!

Gordon Griffith as the first movie Tarzan.

Harold Lloyd in “Safety Last“

The train scene in “Some Like It Hot”

Get the <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com/widget/twidget”>Twitter Widget</a> widget and many other <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com/”>great free widgets</a> at <a href=”http://www.widgetbox.com”>Widgetbox</a>! Not seeing a widget? (<a href=”http://docs.widgetbox.com/using-widgets/installing-widgets/why-cant-i-see-my-widget/”>More info</a>)