Is the universe deterministic, or random? Not the first question you’d expect to hear in a thriller, even a great one. But to hear this question posed soon after the opening sequence of “Knowing” gave me a particular thrill. Nicolas Cage plays Koestler, a professor of astrophysics at MIT, and as he toys with a model of the solar system, he asks that question of his students. Deterministic means that if you have a complete understanding of the laws of physics, you can predict with certainty everything that will happen after (for example) the universe is created in the Big Bang.

Random means you can’t predict anything. “What do you think?” a student asks Koestler, who says, “I think…shit just happens.”

He is soon given reason to doubt his confidence. (From this point on, there are spoilers.) “Knowing” begins 50 years ago with a classroom assignment; grade school children are asked to draw pictures of what the world will look like in the future. Most draw rocket ships. Lucinda covers her page with row after row of deeply-etched numbers. All the pages are buried in a time capsule, and when the future comes around, Lucinda’s sealed envelope ends in the hands of Caleb, Koestler’s young son.

The page seems meaningless, a work of madness. But by chance Koestler notices these numbers in a row: 91120013239. Koestler sees 9/11/2001, and when he googles 9/11 he finds that 2996 people were killed. The numbers were written down in 1959. In a fever, the scientist extracts other numbers and finds the precise dates and fatalities of major catastrophes during the previous five decades.

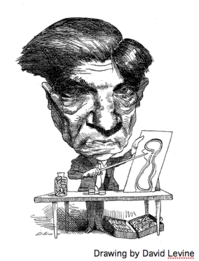

Koestler and the music of the spheres

Koestler and the music of the spheres

How can this be? By now Koestler is in the state of mind that Nicolas Cage evokes so perfectly: Profound, heartsick worry. He turns to his MIT colleague, a cosmologist named Beckman (Ben Mendelsohn). Beckman thinks he must be mad, and warns against the superstition of numerology. But when recent numbers turn out to be correct predictions, and when Koestler realizes that some of the numbers are coordinates of latitude and longitude, it is impossible to dismiss the sheet of paper. It poses a threat to our very understanding of the universe. Shit doesn’t just happen.

As I watched these scenes, I became aware of synchronicity in my own life. It happens that I am still immersed in the never-ending debate about Evolution vs. Intelligent Design on my Ben Stein blog entry (currently 1,530 comments and counting). Only a day or two earlier, a reader named Randy Masters asked me what, in my mind, would constitute proof of intelligent design. Fair question. I replied: “I wouldn’t expect the Big Banger to manifest in the skies like the Four Horsemen or anything. I would expect him to enlighten scientists so they would learn how to find evidence of his working.”

Now, in this movie, a secularist scientist is apparently being furnished with such enlightenment–for how else to explain the numbers? There must be a Design. We learn Koestler is long estranged from his father, a clergyman who serenely believes he will be in heaven with his wife. Aren’t these numbers evidence of a higher power? More importantly, what do they mean for the lives of Koestler and Caleb? And for Diana (Rose Byrne), the daughter of Lucinda, and Abby, the granddaughter (Lara Robinson)? Koestler has tracked them down with feverish intensity.

“Knowing” is a superbly crafted thriller in any event, but that it brings basic philosophical questions into view was more than I could have hoped for. The film is by Alex Proyas, whose “Dark City” (1998) was also about the hidden nature of the world men think they inhabit. “Knowing,” which could not be a more different film, seems to reveal a similar secret.In that film, the hero discovered the occult powers by which an alien race controls the world of men. In Proyas’s “I, Robot” (2004), a robot, whose programming is rigidly deterministic, evolves to the point where it is able to ask, “What am I?”–which of course leads to a discovery of the true nature of the world it inhabits.

Of course it isn’t that simple. The professor offered a false choice to his class. No one thinks the universe is random, except possibly at a quantum level, and let’s not go there. Gravity doesn’t randomly switch off. Light doesn’t randomly alter its speed. The classical philosophical choice is between determinism and free will. Is the future already predestined, or do we have a role in the outcome? Can lower orders like dogs have degrees of free will? Is it already written when the dog will bark, or is it only strongly suggested by its instincts?

The numbers on Lucinda’s page are rigidly deterministic: On this date, in this place, these many people will die, and there is nothing to be done–a fact illustrated when Koestler tries to prevent a subway tragedy, and fails spectacularly. From this I believe supporters of Intelligent Design will take comfort; it appears that Koestler has been given the sort of proof I requested.

These numbers are not random

These numbers are not random

But it’s not quite that simple. For one thing, how do you conveniently get an exact count on a death toll via a cable news flash? It often takes days to find bodies (after an earthquake, for example), and some victims may linger for weeks. And were the numbers dictated by a supernatural power, or by a higher order of natural power? That leads directly to a question at the end of the film.

As you know, there have been appearances all though “Knowing” of mysterious figures standing at a distance. Men in overcoats, alone or in groups of four, regarding the children who can hear them “whispering” in their ears. At the climax, these figures manifest at the site of the house trailer Lucinda lived in as an adult. At first they seem to be human, but then they divest themselves of human appearance and become glowing, transparent, figures of energy and nerves. They beckon Caleb and Abby to follow them as they enter a shimmering vessel that seems to vaguely suggest a geodesic dome or elements of the Martian crystal structure in “Watchmen.”

The vessel takes off, and we see that it is joined by other vessels from all over the globe. Then the sunburst takes place, and the special effects are merciless as the firestorm rips across the planet. The two children are deposited by the vessel in a sun-washed wheat field, join hands, and run toward the only tree on the horizon. A new Adam and Eve in a new Garden of Paradise?

At the moment the mysterious figures cast away their humanity, I fully expected them to sprout wings and manifest as angels, etc. But no. They seem to belong to the natural world, in a form we cannot imagine. The fact that their vessels take off from earth and physically move through space seems to indicate they are meant to be real, no matter what worm hole they may use to arrive at the new planet. (Or do they travel back through time, and start the process on earth all over again?)

If we assume the aliens are real in some tangible sense, how did they produce the numbers? Is Lucinda’s sheet of paper proof that the universe is deterministic, and that the aliens simply possess the intelligence and information to predict the future, as in theory they could? And if so, isn’t their existence a refutation of the existence of God? Strict determinism implies an absence of free will, and free will is a necessary component of all spiritual belief systems.

In this scenario, the aliens would have known they would dictate the numbers to Lucinda, that Caleb would be given them, that Koestler would have behaved exactly as he did, and that the outcome would have been exactly as it was. No suspense for them. And the aliens and all of their actions would have been foreordained from the instant of the creation of the universe. That leaves the possibility that a higher power created the universe, but denies that power any role in its subsequent behavior.

My guess is that many audience members will experience the film as an affirmation of religious belief. Few will bother to think through the implications, which seem to make religion irrelevant–except as a comfort to those like Koestler’s clergyman father.

All of my considerations are probably irrelevant to enjoyment of the film. But the film inspired me to think in these ways, and not many films do. It was exciting while watching “Knowing,” and while trying to puzzle it out. Just on the fundamental level of a movie-going experience, I think Proyas’s film is a great entertainment, one of those Bruised Forearm Movies where you’re always grabbing the friend next to you. Nicolas Cage, a remarkably versatile actor, embodies the role. He internalizes doubt and fear, until they gnaw at his character. He plays a man of action always fearful of inadequacy, a hero by the seat of his pants. The young actors Chandler Canterbury and Lara Robinson (who plays both little girls) are uncommonly good at projecting deep solemnity, not easy for children. “Knowing,” as I sometimes like to say, is what going to the movies is all about.

Footnote: The names of the characters inspire some associations.

Koestler. For Arthur Koestler (left), of course. After writing such novels as Darkness at Noon, Wikipedia notes, “mysticism and a fascination with the paranormal imbued much of his later work.” His The Roots of Coincidence is “an overview of the scientific research around telepathy and psychokinesis and compares it with the advances in quantum physics at that time.”

Lucinda Embry. “Lucinda,” to quote from thinkbabynames.com, “is based on Lucine, the Roman goddess of childbirth, giver of first light to the newborn.” Her surname “Embry” needs only one more vowel.

Caleb. Is of Hebrew origin, and its meaning is “dog.” In the Bible, “Caleb, a companion of Moses and Joshua, was noted for his astute powers of observation and fearlessness in the face of overwhelming odds.” And, “dog” spelled backwards is…

Why critics hate “Knowing“: Do wings have angels?

Philosopher David Sosa on determinism and free will

Alan Watts on freedom from determinism

Daniel C. Dennett on free will and determinism