“Zebrahead” is not so much a movie as notes toward a movie – a good one, judging by what’s on the screen. The strength of the central story is undermined by loose ends and subplots that are hinted at but never developed, and watching the film is a little like solving a puzzle. If the director didn’t have the money to finish what he started – and apparently he didn’t – then he should have been more merciless in his editing, leaving out the footage that’s distracting.

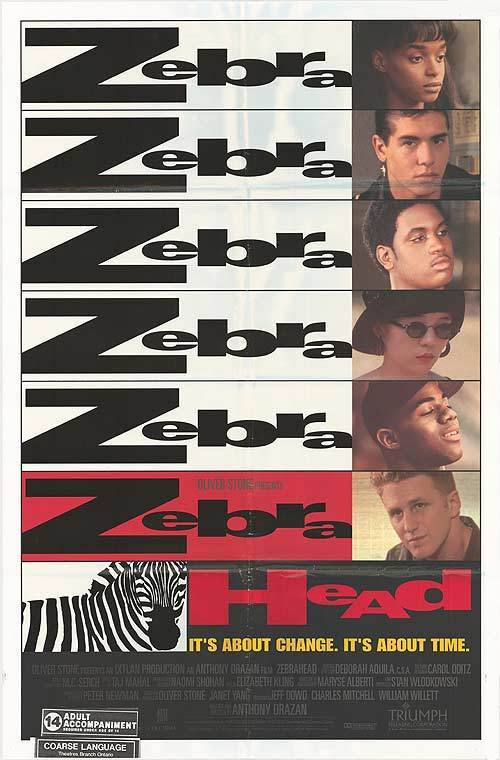

The movie takes place in Detroit, where a Jewish teenager named Zack (Michael Rapaport) and his best friend, a black kid named Dee (Deshonn Castle), go to school together. One day Zack sees Dee’s cousin Nikki (N'Bushe Wright), likes her looks, and somewhat shyly asks her out. Neither one has dated interracially before, but they have a lot in common and before long they’re going steady.

Their romance causes ripples in their families and high school circles. Nikki’s mother is totally opposed to her daughter dating a white boy.

Zack’s father (Ray Sharkey), an unprincipled womanizer, approves of his son dating any woman. Dee is all right about his best friend dating his cousin, but there is outspoken anger from another young black man in the neighborhood, Nut (Ron Johnson), who wants to date Nikki himself.

Surrounding this story are all sorts of loose ends. There are, for example, a couple of scenes in which another neighborhood boy, who is never really explained, lights fires in his lawn. I under stand from an interview with the director, Anthony Drazen, that these scenes are part of an environmental subplot about natural gas seeping to the surface. Fine, but since they’re not explained, the scenes are a dead end.

The movie is also awkward in the way it handles Zack’s home situation. His mother is dead, and his father (Sharkey) apparently has only one goal in life, to have sex as often as possible. There is a badly handled scene in which Zack, Nikki and the father have breakfast together, and it is implied that the father would like to sleep with his son’s girlfriend. The implication is never made clear, nor is the relationship between father and son well-handled; later, Zack tells Nikki “you know how my father is” – but the problem is, we don’t.

Zack takes Nikki to a party, where, in an awkward scene, she overhears him telling his friends, “The blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice.” This enrages her, and she breaks off their relationship until Zack apologizes and wins her back again. Fine, except the original remark seems contrived – stuck in to force them into an argument – and, in context, Zack’s remark is more affectionate than offensive.

Then there is the business of Nut, the angry youth across the street, who wants to date Nikki and eventually forces a violent confrontation at a skating rink. One of the characters is shot dead, after which the high school kids hold an inconclusive discussion about the meaning of it all. Well, what is the meaning? The movie seems to be saying, simultaneously, that people should be free to love who they choose, and that crossing racial lines can stir up a lot of trouble. (The real message may be, we desperately need handgun control.) Because “Zebrahead” is about a rarely seen subject and because the director made it on a limited budget, it has received a lot of praise – more than it really deserves. One writer even said it does what Spike Lee’s “Jungle Fever” tried and failed to do. “Jungle Fever” is much the better movie, but both films have the same flaw, which is that they use the interracial romance as a clothesline on which to hang many other issues, including urban violence. We never get many scenes in which the two lovers actually relate to one another, so that we can believe that their partnership is more than skin deep. Instead, the plot is artificially cluttered by hotheaded kids with guns and unrealized subplots about pollution.

The performances are solid. Rapaport and Wright have engaging screen presences, and it’s a shame the movie didn’t allow their characters to relate more deeply and at greater length, so that we could feel they were people, instead of story elements. Sharkey is interesting as the randy father, but seems to belong in another movie. And the violence at the end sends a nihilistic message: Don’t bother to dream your dreams, to love, to be a friend – because the rotten world will just shoot you dead anyway.

I don’t believe it.