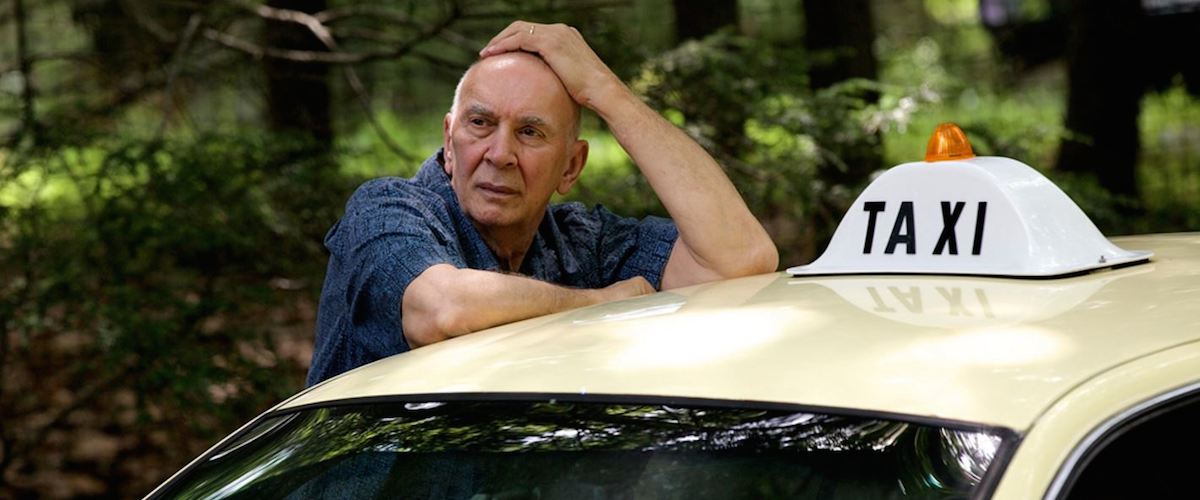

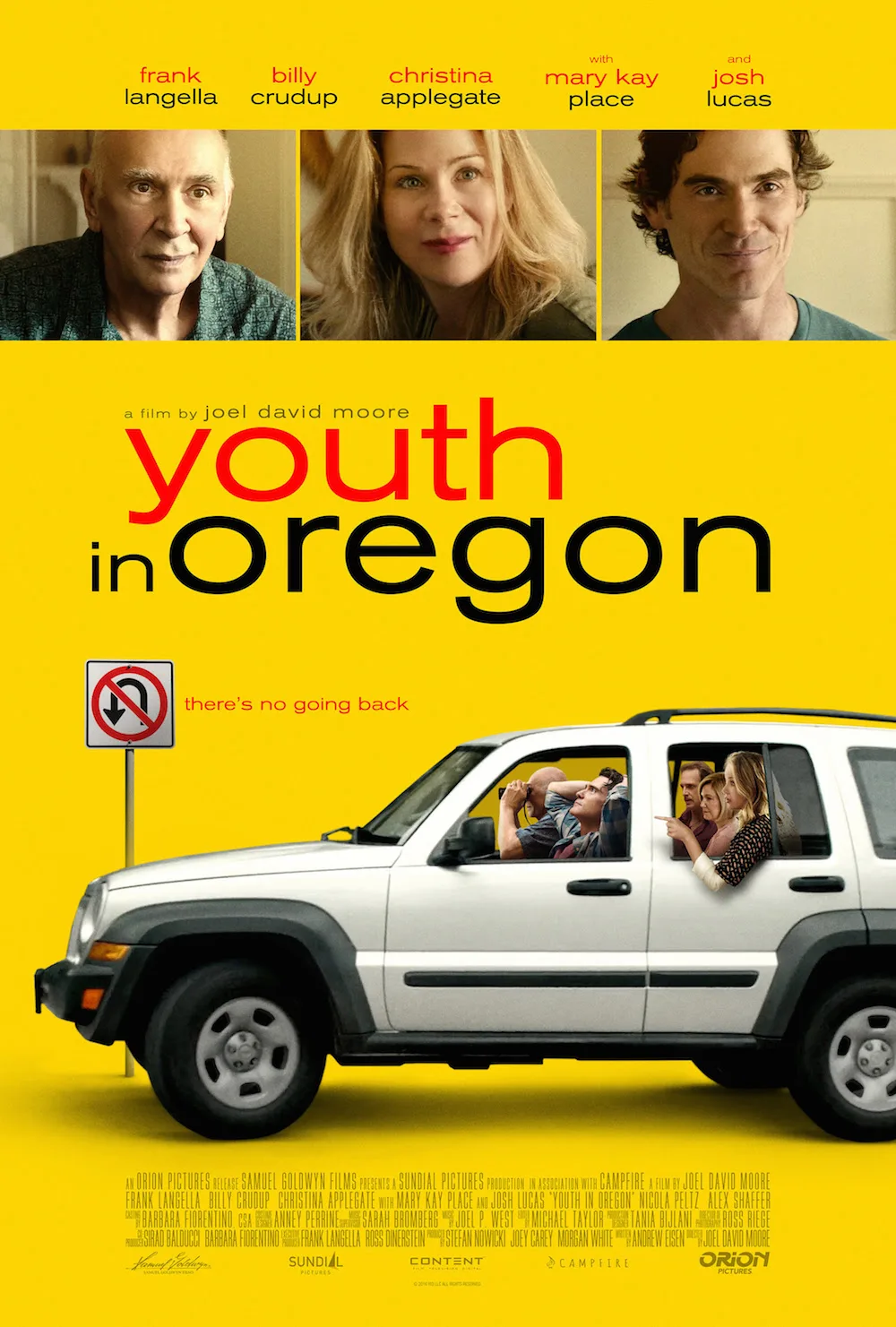

This is a big month for bad wordplay in independent film titles. There’s a picture opening called “Dark Night” which was inspired by the 2012 movie theater shooting in Aurora, Colorado, where another movie whose name you’ll never guess was screening. As for this item, directed by Joel David Moore (who’s also a reasonably busy character actor, although he doesn’t appear here) from a script by first-time-feature-writer Andrew Eisen, it is not a movie about young people in Oregon, as one might glean during the opening of the film, which designates Frank Langella as the lead actor and shows him, shirtless, in front of a bathroom mirror, being not terribly youthful. No, the title is a play on the word “euthanasia.” Langella’s character, newly 80 years old, lives, imposingly, in the house owned by his adult daughter Kate (Christina Applegate) and her husband Brian (Billy Crudup). Things are a little crowded in the house: Kate and Brian have two kids, hot-to-trot (if you’ll excuse the expression) cheerleader Annie (Nicola Peltz) and rather more withdrawn Nick (Alex Shaffer), and Langella’s Ray has a wife, Estelle (Mary Kay Place). The movie begins on a busy morning. Brian’s asked to attend a clogged toilet, Annie’s taking under-the-shirt selfies to text to her football-player boyfriend, and the ceaselessly cranky Ray has a doctor’s appointment.

At said appointment, Ray learns that the heart surgery he had a couple of years before hasn’t entirely fixed his problems, and he confidentially tells his doctor he doesn’t want any new surgery. That evening, at a party for his 80th birthday, upstaging an egregiously overacting waiter who goes on at length about a meal served with “a creamy white sauce with herbs and spices” (seriously, the guy comes on like he’s in a Monty Python sketch), Ray gets up and announces that he has decided to die, and that he wants to go to Oregon, where he owns a property and where the laws pertaining to checking out with extreme prejudice are somewhat agreeable, and get it over with. The thing is, he insists on going from the East Coast to Oregon by car, because he doesn’t fly. I know, I too raised an eyebrow at a character who is hell bent on ending his own life but won’t take an airplane to get to he place where he’s going to do it. But this is the kind of movie “Youth in Oregon” is: a movie that has to have a Road Trip, because it will only be through a Road Trip that the characters can go through the kind of self-discovery that is the very raison d’etre of such entertainments.

And so, with Brian offering to drive even though he thinks he’s faking out Ray and Estelle—the idea is he’ll talk some sense into his father-in-law and they’ll all drive back home together—the journey, accompanied by a solemn original music score fueled by minimal piano and mournful cello, begins. Ray insists on listening to birdcall CDs in the car. Stopping for lunch, he gets tetchy about not getting any mayo on sandwich, and when Brian wryly brings up Viagra for some reason, Ray gets to boasting about past sexual prowess, and loudly, so the “feisty old guy acts embarrassingly in a restaurant” requirement is checked off. As Brian’s driving falters on account of being tired, Estelle, apparently a current or former nurse, offers him some uppers, and indulges a bit herself, so the “comedic bonding via pharmaceuticals” requirement is checked off. And so on. At Salt Lake City, Josh Lucas turns up as Ray’s estranged son, and the resentment between them is so thick that of course this character is the only one in whom Ray confides his condition. Back home, Annie keeps giving Kate trouble, and the movie gets padded in an unusual way, that is, with the suggestion of a sex scene between Annie and the aforementioned football player boyfriend (Will Janowitz). They’re supposed to be on the outs because the aforementioned under-the-shirt selfies leaked to the high school populace in general, and when Kate walks in on the bubbling-up action, she is none too pleased. Yeah, I don’t know either.

And on it goes, all coming together in the foreshadowed Oregon property (which is well-kept in the way that such places are only in some movies) and with one character pleading “Please help me fix our family” followed by a requisite reverse shot with a wide angle lens taking in a beautiful view of nature to contemplate as a human gesture of reconciliation is contemplated, then executed. Is this all well-acted? It certainly is, especially by Langella. But all things being equal, I’d prefer to see him in a revival of “The Man Who Came To Dinner.”