For sheer consistency of both artistic vision and high-quality output, perhaps no current European filmmaker except Pedro Almodovar can match the sustained brilliance of Belgium’s Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne. Since first gaining critical attention with 1996’s “La Promesse,” the brothers have made nine features that have kept them in the top tier of international festivals, including Cannes, where they are regular prize-winners.

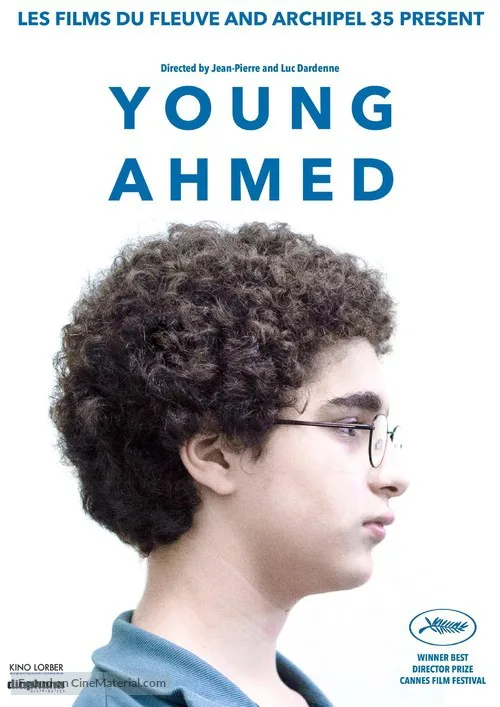

Their latest, “Young Ahmed,” which won the Best Director trophy at the last Cannes, is consistent with their past work yet also something of a departure. Like all of their films, it takes place in present-day Belgium and deals with characters on the margins of society; like previous Dardenne masterpieces including “La Promesse,” “The Son” and “The Kid with a Bike,” it has an adolescent protagonist. The film’s difference lies in the fact that this protagonist, 13-year-old Ahmed (Idir Ben Addi), is a Muslim and an aspiring terrorist.

Although he looks like a normal teen with his knapsack and blue jeans, Ahmed and his older brother Rachid (Amine Hamidou) have become adherents of Imam Youssouf (Othmane Moumen), a charismatic local clergyman who preaches an austere form of Islam that is not without its political implications. Ahmed, though, has embraced the faith far more seriously than Rachid, who still likes to joke around with friends. Dour and unsmiling, the bespectacled younger boy spends his time obsessing over his ablutions, prayers and memorizing verses from the Quran and hadith.

This newfound fervency is not playing well at home, where Ahmed lives with Rachid, their sister and their mom (Claire Bodson), who evidently wasn’t raised a Muslim and is confounded by her son’s sudden transformation. Only a month before, she recalls, Ahmed stopped playing video games and took down the posters from his bedroom walls. Now he infuriates her by criticizing her drinking wine and berates his sister for her way of dressing. A happy family this is not, and in a certain light, its most significant member may be the absent father.

Another absent figure also plays a role in Ahmed’s outlook: a cousin who sacrificed himself waging jihad against the “Jews and Crusaders” in the Middle East. Ahmed may have given up his video games, but he’s still as plugged into the internet as any teenager, only now he watches videos extolling righteous martyrdom and the glories of armed struggle. And while his imam may vaguely counsel that jihad is for distant lands in future, not right here, right now, Ahmed is several steps ahead of his mentor: he wants to put his new convictions into action immediately.

In the bitterest of ironies, his chosen target is the person who has been kindest to him. His teacher Ines (Myriem Akheddiou) has devoted extra attention to helping him academically, and clearly is fond of the boy, but she has the effrontery to insist on shaking hands with him and generally represents a more liberal and modern form of Islam, all of which makes her an enemy that Ahmed decides he must eradicate. So one day he shows up at her apartment determined to dispatch her, but he botches the deed and is quickly arrested.

In its second half, “Young Ahmed” follows its protagonist through the legal system, which includes a stint on a farm where youthful offenders are given the care of cows and other animals as a form of therapy. In this portion of the story, which almost plays like a Frederick Wiseman documentary on the institutions of criminal justice in Belgium, Ahmed is immersed in a world of police, judges, lawyers, psychiatrists, counselors and wardens, all of whom do their jobs with consummate professionalism and, in many cases, what seems like genuine concern for the young man, who is allowed to continue his ablutions and prayers on his own strict schedule. Here, it almost seems like the Dardennes are asking what a modern, western, secular society like Belgium—with all its skills, tolerance and science—can do to reform a fanatical miscreant like Ahmed. The implicit answer: Not much. As soon as the boy is able to wrest free of his incarceration, he’s back on the jihad trail.

The problem with giving a story synopsis of a film like “Young Ahmed,” though, is that it inevitably misses what’s most crucial to the movie’s impact: the narrative tone expressed through the Dardennes’ very precise, carefully understated style. Clearly descending from the humanistic ethos of Italian neorealism, while also influenced by their own work in documentary filmmaking, the directors’ approach is one that looks at all the people in the story with a kind of contemplative compassion. Like all of their films, “Young Ahmed” contains a range of superbly realized performances—young Ben Addi in the title role deserves special commendation—that brings to life not just a disparate set of individuals but an entire social world. Yet it’s the vision of the entire film which makes that world so immediate and affecting.

If that vision can be described as moral, it’s also, at its base, essentially religious. From its beginnings, the Dardennes’ work has evoked comparisons to the films of Robert Bresson, in which a stripped-down, all but minimalist aesthetic is put in service of stories that convey the director’s austere Catholicism. Though it’s hard to imagine Bresson dealing with a Muslim protagonist, “Young Ahmed” has points in common with “The Devil, Probably” and other Bressonian tales of spiritual despair. Yet this film doesn’t give in to despair or easy condemnation. Remarkably, it never ceases to see Ahmed as a human being, not a monster, a boy who is not identical to his beliefs, no matter how poisonous (or obviously connected to sexual pathology) those may be.

It might be said that the Dardennes’ great theme is redemption, the belief that even the most benighted souls can find their way toward the light, given the ineffable assistance of grace. That they are able to discern this Christian concept even in the tale of a desperate fanatic of another faith is what makes “Young Ahmed” one of their most extraordinary masterpieces.