“Yossi” is a modest movie about a closeted Israeli cardiologist still living in mourning a decade after his lover’s death. It’s serious about its characters and their emotions, but still finds room for humor.

The film is a sequel to director Eytan Fox’s 2002 breakthrough “Yossi and Jagger,” a romance about two men who fall in love while serving together in the Israeli army. Yossi (Ohad Knoller), one half of the earlier film’s titular couple, now works in a Tel Aviv hospital. He is a workaholic, well-liked but intensely private. He sleeps in hospital beds between shifts, and tries to keep his colleagues — including a nurse (Ola Schur-Selektar) who has a crush on him and an irresponsible doctor (Lior Ashkenazi) who wants to be his friend — at arm’s length.

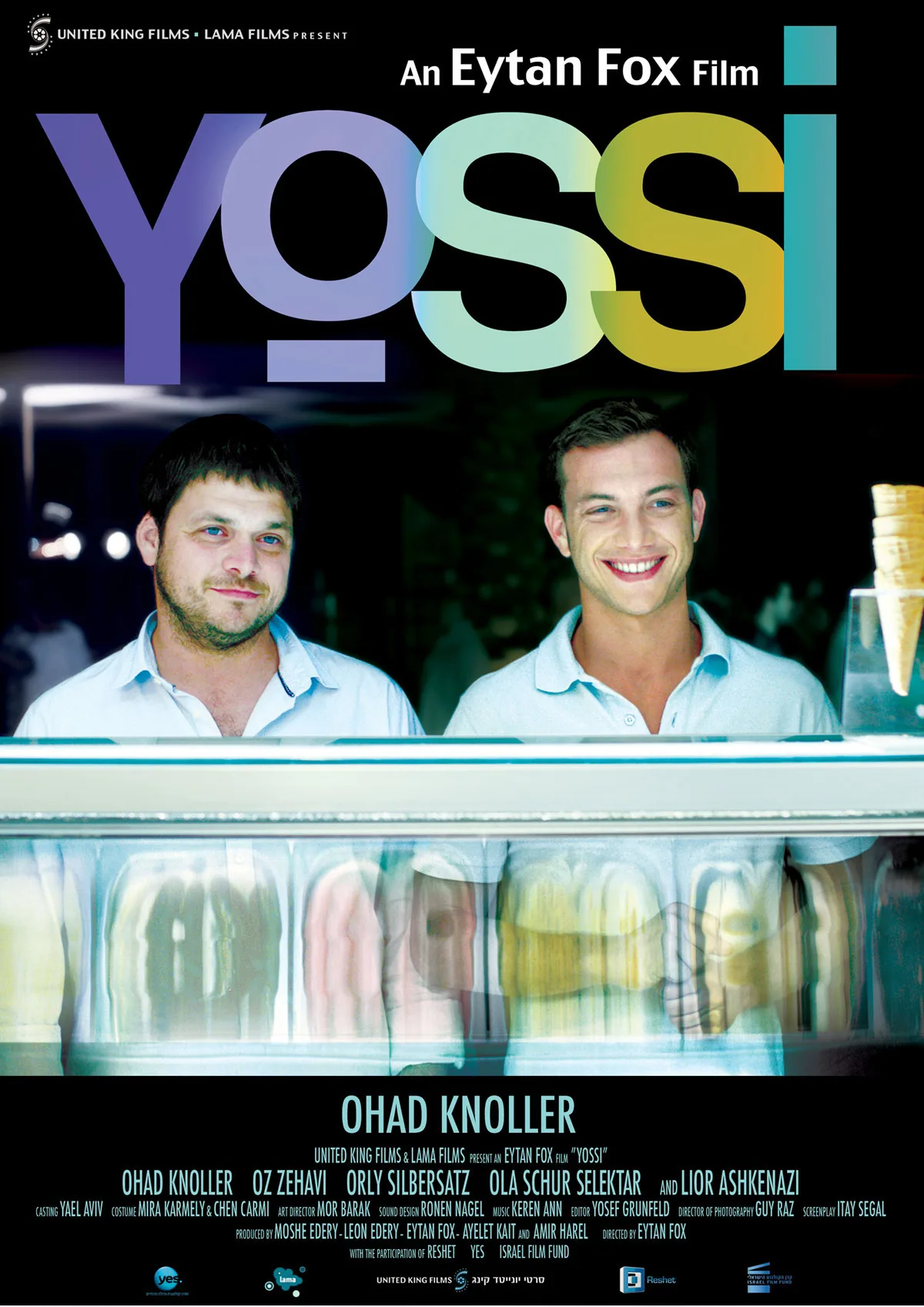

Yossi lives in a double bind. On the one hand, he isn’t comfortable enough with his co-workers to let them know that he’s gay. On the other, he isn’t comfortable enough with his aging body — ten years older and a good forty pounds heavier than he was in “Yossi and Jagger” — to pursue relationships.

In one the movie’s standout scenes, Yossi goes to the apartment of a potential hook-up. The two had met online, and upon finally meeting in person, the other man calls Yossi out — gently but sharply — for deceiving him with old pictures from his army days. In short, Yossi lives in the past — partly out of self-loathing, partly due to trauma. To him, the present is little more than a blur of work, sleep and online porn.

“Yossi” follows him as he slowly, painfully learns to let go of the past, first by telling Jagger’s parents (Orly Zilbershats, Raffi Tavor) about their relationship and then by going on vacation to the resort town of Eilat. There he meets up with a friendly group of soldiers — one of whom, Tom (Oz Zehavi), is openly gay. Not everything that happens in “Yossi” is necessarily believable, but it is all credible, thanks to the performances and to screenwriter Itay Segal’s finely-tuned — and often funny — dialogue.

“Yossi”‘s one major flaw is its style, or lack thereof. It looks and moves like a cable TV show — something that would play on FX or AMC. There’s a fine line between being pragmatic and being tone-deaf, and at certain critical moments Fox errs on the side of the latter. For instance, a crucial late scene — which could be moving if it were, say, presented as a single take — is undercut by the editing. The scene involves Yossi disrobing — in a sense, coming to terms with his body — but is edited to obscure his nudity. Fox’s shot choices are practical, not emotional, and the result robs the moment of any sense of catharsis.

Still, Fox manages to make up for some of his shortcomings as a visual stylist with his talent as a director of actors. Facial expressions, speech rhythms, and body language fill in emotional gaps. As Yossi, Knoller is especially excellent: his unflatteringly scraggily beard, slow walk, and slumpy posture suggest exhaustion and depression. His sad eyes — saddled with big insomniac bags — communicate everything the camera doesn’t.