”This is not a political film. The mantra is ‘This is not a political film.'” — Oliver Stone, New York Times (July 2, 2006)

“It is one of the greatest pro-American, pro-family, pro-faith, pro-male, flag-waving, God Bless America films you will ever see.” — right-wing syndicated columnist Cal Thomas (July 20, 2006)

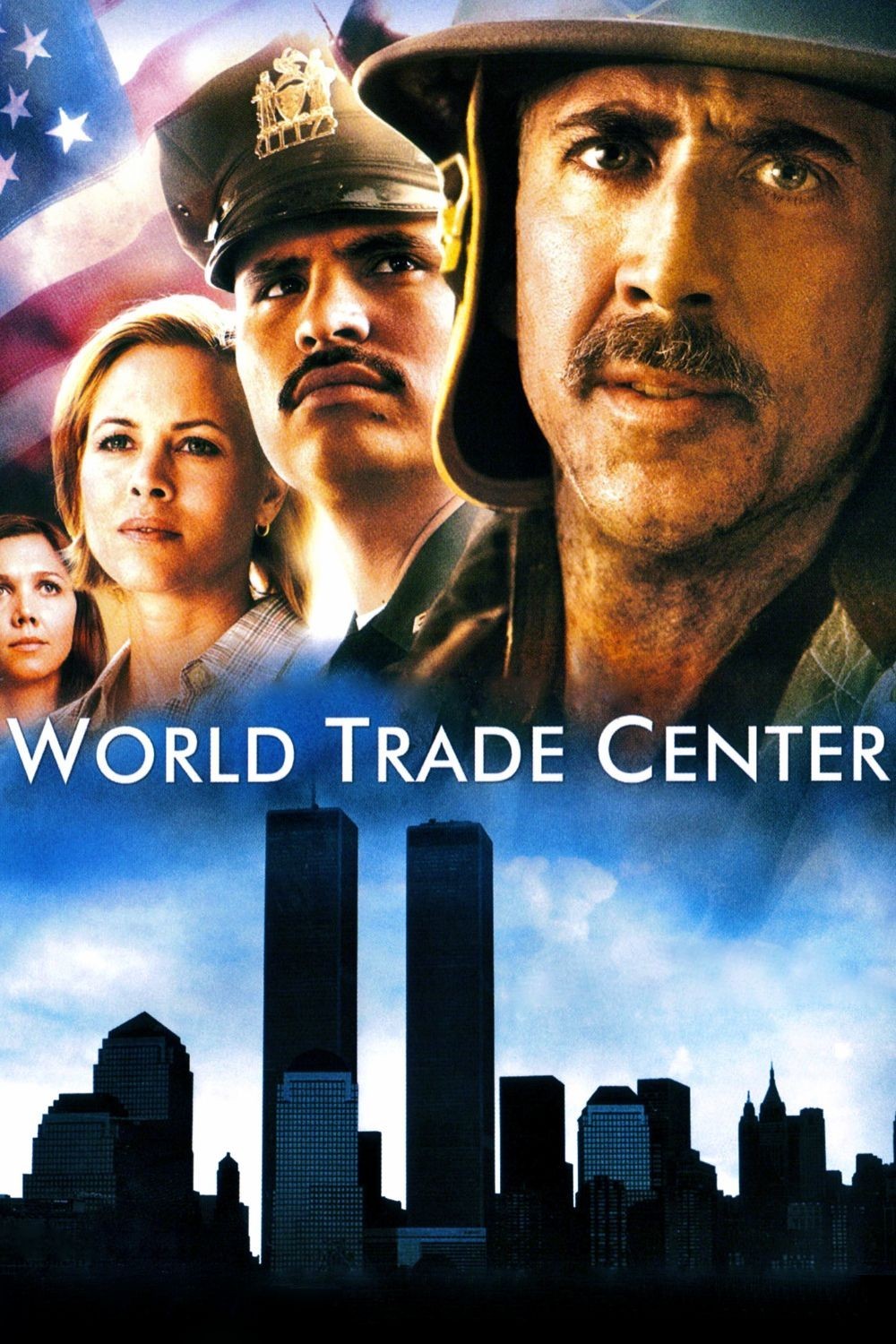

“World Trade Center” is about two men who, against all odds, survived the collapse of the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001. It combines fragments of two movies — the one that Stone describes above, and the other that Cal Thomas flips over. It is a disaster movie and a feel-good inspirational movie — both based on true stories — and that is why I am of two minds about it.

While trapped in the rubble, Port Authority Police Officer Will Jimeno (Michael Pena) talks about a little girl who survived after four days of being buried under debris after an earthquake in Turkey. Which raises the question: What if this were a movie about some other disaster, man-made or natural, real or fictional, instead of about 9/11? Would American moviegoers respond to it any differently than they did to, say, “Poseidon“? Or is the movie just exploiting still-tender emotions about 9/11 to sell another “Amazing Rescues” episode — Based on a True Story, but essentially indistinguishable from countless other such stories from around the world and throughout history? That’s something viewers will weigh for themselves as they watch this film.

Seen strictly as a movie (a PG-13 disaster movie or an exploitation movie or an inspirational movie or however you may see it), “WTC” is a tale divided against itself. The scenes between the two officers, Sgt. John McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage) and Jimeno, pinned and immobilized, trying to keep each other alive in the pit of hell, are the best in the movie, because they feel the most authentically personal. You’re right down there with them, and the actors play it for real. There’s no need to overdramatize something as inherently dramatic as this.

Stone keeps his camera tight on these guys, conveying palpable sensations of weight, heat, dust and claustrophobia, and resists what must have been (for him) a powerful temptation to crank up the piano-and-strings. He overdoes the slow-motion in the early scenes, which fail to convey the overwhelming chaos most people who were there describe. And there are a few show-off CGI shots (like one that rises through the tangled debris and high up into the air above the vanished towers) that seem almost decadently gratuitous, but this is Oliver Stone, The Man With the Movie Mallet, so you get what you pay for.

Stone is uncharacteristically restrained and respectful in his treatment of these men and their families. Which is why the larger-than-life approach he takes to mythologizing the journey of USMC Staff Sgt. Dave Karnes (Michael Shannon), the film’s Hero with a capital “H,” feels so jarring and inappropriate. The real-life Karnes made his way to Ground Zero on September 11 because he saw a job that needed to be done, and knew he had to do it. His actions are authentic and unquestionably heroic, and they should have been allowed to speak for themselves.

Instead, Stone turns him into a monumental cypher, pumping him up with extra music and shooting him from portentous (and pretentious) low angles so that he’s practically the Third Tower. Karnes is portrayed a man of determination and few words (when one of the rescue workers asks what he can call him for short, Karnes replies, “Staff sergeant”). But Stone pours on the gravitas, and gives him a speech that seems too flowery for his character. Karnes arrives at Ground Zero and proclaims that it is “like God made a curtain with the smoke to shield us from what we’re not ready to see.” I don’t know if Karnes actually spoke these words or not (though it seems a peculiar thing for a rescuer to say to another rescuer when he knows his mission to go behind that “curtain” and search for survivors), but as it’s depicted in the movie it strikes a resoundingly false note. The phrase “less is more” just isn’t in Stone’s directorial vocabulary. (He could take some lessons — as could we all — from Rudy Giuliani’s flawless behavior and no-nonsense eloquence on that day. Speaking of casualties: “I don’t think we want to speculate about that — more than any of us can bear.”)

Karnes is introduced dressed as a civilian, watching TV like everyone else. “I don’t know if you guys realize it yet, but this country’s at war,” he says, and strides out of the frame. It’s clear he’s decided to do something about it. Cut to a close-up of a bible, open to the book of Revelation, followed by a shot of a looming cross. This is piling it on a bit thick for a movie that otherwise emphasizes the personal over politics and religion. Stone overtly Christianizes 9/11 in ways that go beyond the beliefs of his characters. A glowing apparition of Jesus appears twice, but the first time it just comes out of nowhere, and is followed by a memory-image of McLoughlin’s wife. Where is this Jesus coming from? The second time it’s directly tied to a character, and consequently feels natural and appropriate. You believe that’s what this guy experienced, not just what the filmmaker is telling you to see.

One other moment that exemplifies how “WTC” loses credibility above ground: a former paramedic (played by the great, underused actor Frank Whaley) who has lost his license finds his better self in helping to rescue Jimeno and McLoughlin. It’s movingly done, up until his very last moment in the picture. When a volunteer asks him what he does, Stone cuts to another of those low-angle shots he weilds like a club, and lets a heavy pause hang in the air before he replies: “Paramedic.” What an insult — to the character and the audience. It throws you out of the movie by reminding you that you’re watching a Hollywood movie. The scene would have been so much more moving if Stone had not underlined it three times and italicized it. Instead, the character is over-sentimentalized and leeched of some of his humanity in the process.

In other ways, Stone does emphasize the individual human stories. The cause of the devastation is never addressed, except in a few lines of dialog about “those bastards.” But, of course, “WTC” is about 9/11, so it can’t help but be political — from its choice of TV clips to what it chooses not to show. As Stone told the New York Times: ”It seems to me that the event was mythologized by both political sides, into something that they used for political gain,” he says. ”And I think one of the benefits of this movie is that it reminds us of what actually happened that day, in a very realistic sense.” Not entirely realistic, but it’s a PG-13 movie about mass murder — somewhat sanitized to reach a wider, and younger, audience.

The problem with movies about individuals in such extreme situations (perhaps especially those that try to hew closely to the accounts of the survivors who lived the events depicted) is that they are stripped of some of their individuality. They are, by necessity, reduced to human essentials, and that doesn’t always make for good movie drama. Yes, anyone in this situation would think, and probably say, something like, “Tell my wife and children that I love them.” But since we don’t know much about who these guys were before 9/11 (presented here as a hazy day rather than the crystal clear fall morning we remember — where’s CGI when you need it?), some moments in “WTC” feel more generic than personal or universal.

Stories of survival need to be told, and “World Trade Center” needs to be seen in perspective, as an early (five years later?) attempt to deal with a galvanizing tragedy in the lifetimes of many Americans. In ten years (or even next week), I don’t know that this will be seen as anything more than an average TV movie about a not-so-recent disaster. “WTC” is not a definitive statement about 9/11, or one that is likely to make you see that day any differently than you do now. And there’s nothing wrong with that. But I was reminded of what Stanley Kubrick said about “Schindler's List“: “Think that was about the Holocaust? That was about success, wasn’t it? The Holocaust is about six million people who get killed. ‘Schindler’s List’ was about six hundred people who don’t.” That’s perspective.

A closing voice-over states the movie’s theme, to the effect of, “I saw good that day.” And it’s true — catastrophe can bring out the best in people, more than they even knew they had in them, and 9/11 witnessed countless heroic, compassionate and selfless acts. But perhaps the most emotionally resonant moment in “WTC” comes in a passage after the collapse of the towers, when the movie flashes to televised reactions from all over the globe. It’s a reminder that 9/11 also represents a missed opportunity. In addition to remembering the victims and the many who risked — and gave — their lives trying to help others, it’s important to remember the intense, “We are all Americans” outpouring of grief and sympathy that united so much of the world on that day, and for just a few days or weeks afterwards, before politicians had reduced 9/11 to an election slogan. And it’s a sad, terrible reminder of the enormous good we’ve lost in the five years since. Had we been able to build on those feelings, it would have been the most constructive and meaningful tribute to those who were killed, and to their families, and to those who survived. Maybe this is a political movie after all.