Late on the night of June 9, 1982, the West German film director Rainer Werner Fassbinder made a telephone call from Munich to Paris to tell his best friend he had flushed all his drugs down the toilet — everything except for one last line of cocaine. That was the line that killed him. He made his first film at the age of 22, and 40 films before dying at 36. So there should be another 50 or 60 films. Could he have maintained his incredible output? We will never know. What is remarkable is what a high standard he maintained, what a stylistic vision he produced on such small budgets.

In the treasure of his work, it’s not surprising that “World on a Wire” (1973), a two-part, 212-minute science fiction project for West German television, went unseen in the rest of the world for many years. Only now is it being shown in the U. S., earlier at the Museum of Modern Art and now at the Siskel Film Center. It involves a familiar sci-fi theme: The possibility that this entire world exists entirely inside another world, perhaps as a computer simulation.

I don’t believe we’re expected to be shocked by that possibility. The story centers on Stiller (Klaus Löwitsch), an engineer who works for a program named Simulacron, which fabricates complete identities for characters who don’t know they’re unreal. In the film, Stiller and others discuss the notion that reality is unreal, tracing it to Plato. The purpose of Simulacron is said to be the prediction of consumer trends 20 years into the future, although there may be a more sinister purpose. It’s possible to imagine all the creatures inside Simulacron as living in a sort of SimCity controlled from a higher level. Or are perhaps the fabricators of Simulacron themselves manipulated by still higher puppet masters?

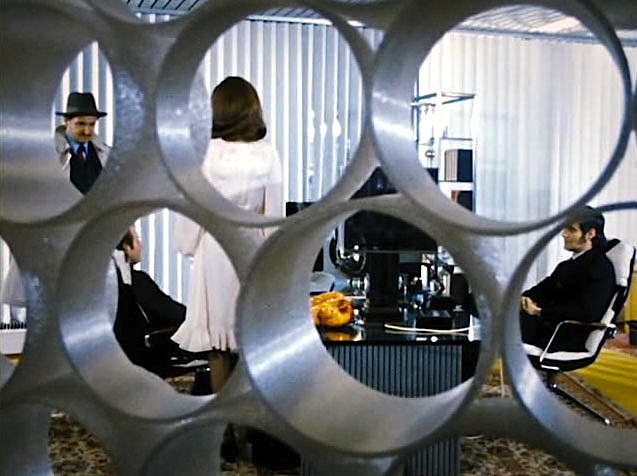

I’m not convinced Fassbinder really cared. The plot for him simply provides an occasion to demonstrate the way he imposed his visual and dramatic style on characters who were often played by the same actors, who spoke in the same mannered melodramatic manner, who inhabited worlds in which everyone seemed aware of artifice.

Stiller’s dilemma is that his world, whatever it is, doesn’t add up. He works for Vollmer (Adrian Hoven), who has programmed Simulacron. Vollmer discovers something about his program before mysteriously disappearing, and Stiller believes he destroyed himself in despair. Then Lause (Ivan Desny), head of security for the firm, disappears. At one moment he’s at a party, speaking with Stiller, and at another moment he’s gone, his chair empty, — and, more alarmingly, no one there realizes he was there or has even heard of Lause. Nor is there any record of him.

Fassbinder’s camera massages his characters, gliding through elaborate spatial movements as if somehow their lives are connected in an occult way with the arrangement of space and time. The dialog is usually arch and ironic. The mannerisms — the smoking, the drinking, the sexual display — are affected. Recognizing such actors as Margit Carstensen (“The Bitter Tears of Petra Van Kant”), we realize we could be witnessing what they do, entirely arbitrarily, in this movie when they are not in that one. Fassbinder is their Vollmar. Perhaps Stiller represents all those fascinated by Fassbinder and how he lived and thought.

“World on a Wire” is slowed down compared to most Fassbinder. He usually evokes overwrought passions, sudden angers and jealousies, emotional explosions, people hiding turmoil beneath a carefully-posed surface. Here there’s less of that emotional energy. But if you know Fassbinder, you might want to see this as an exercise of his mind, a demonstration of how one of his stories might be transformed by the detachment of science fiction.