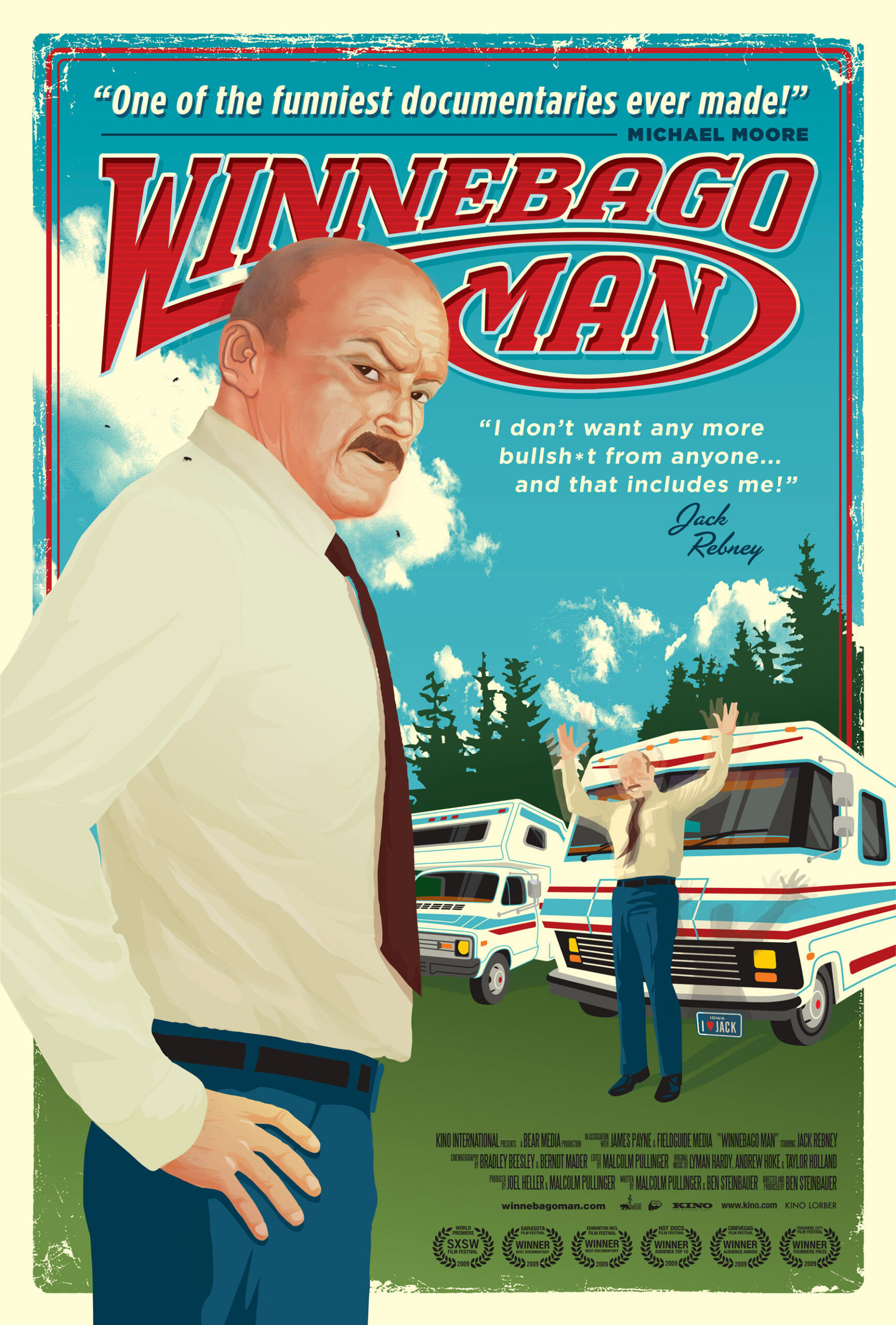

A documentary about Jack Rebney.

There is a video on YouTube that has had millions and millions of hits and made its subject, a man named Jack Rebney, internationally known as “Winnebago Man.” He is perhaps even as famous as Trololo Man, and that’s famous.

Rebney first attracted attention when an old VHS tape surfaced featuring the out-takes of a 1989 session when he was trying without much success to star in a promotional film for Winnebagos. Things were not going well. In take after take, Rebney blew lines, forgot lines, thought lines were stupid, was distracted by crew members moving around, was annoyed by stray sounds, was mad at himself for even doing the damn thing.

Every time the filming breaks down or Rebney calls a halt, he explodes in remarkable verbal fireworks. The only reason “Winnebago Man” doesn’t consist of wall-to-wall f-words is that he separates them with other four-letter words. Once it made it onto You Tube, the video was found hilarious by countless viewers. But what were they laughing at really, and who was the real Winnebago Man?

A documentary maker named Ben Steinbauer decided to find out. He was curious about the reasons we like footage of real people subjecting themselves (usually unwillingly) to ridicule. Are we laughing at them, with them, or simply in relief that we aren’t them? How does their viral fame affect them?

Jack Rebney seemed to have disappeared from the face of the earth. Using methods he shows in his film, Steinbauer finally tracks him down in Northern California, where he lives alone in the woods, calls himself a hermit, and wants nothing to do with nobody — never. That’s not because of the YouTube video, which he doesn’t give a $#!+ about. It’s because of the way he is.

Now around 80, he works as a caretaker for a fishing resort that, it must be said, is never very evident in the film. He has an unlisted phone number, uses post office boxes, and his dog is all the company he wants. He does have a computer; I imagine figures like this feeding the endless comment streams on blogs.

Steinbauer visits him, chats with him, gets first one impression and then another. Rebney more or less agrees to be filmed. His YouTube fame is meaningless to him, but he figures it might be useful if he could parlay it into a way to air his views. Rebney, as you might suspect, has a great many views, including a roster of national figures he believes should be tried as war criminals.

Although we find out a lot about this virtual hermit and develop an admiration for his cantankerous principles, the movie leaves some questions unanswered. We learn that Rebney is threatened with blindness. We wonder how he will get along, at his age, living in a cabin in the woods. We might like to know a little more about Rebney as a young man. We suspect, but can’t be sure, that much of his anger is not uncontrolled, but is aimed consciously at what he considers a stupid and corrupt world. He is not a comic character; he’s dead serious.

Rebney is not touchy-feely. He is a hardened realist, whose only soft spot may be for his dog. He keeps up with events, feels the nation is going down the drain, and isn’t sure why he was so angry while making the Winnebago promotional film. The crew he was cussing out were not good sports, and the outtakes made their way to Winnebago, which fired him. Then it went wide on You Tube.

Steinbauer takes Rebney wider still — all the way to the Jay Leno show, and to a fascinating personal appearance at a Found Film Festival, where he regards himself on the screen and then goes out to speak and proves himself the master of the situation. Steinbauer even sets him up with a Twitter account, but, typically, Rebney loathed it. His most recent Tweet, on March 28, 2009, was: “UP YOUR FERN.”